-

Blue RePeter: A Fact-Based Addendum

In a fairly typical example of the blog almost-not-quite timing things properly, the last update (marking the history of Blue Peter after I reveal it as the sixthmost broadcast BBC programme of all-time) happened to appear a few days shy of Blue Peter’s 65th anniversary. Of course, if I’d planned things properly, I would have waited until the day itself. But since when has planning things in a proper and timely fashion ever helped anyone?

Oh. Ah.

ANYWAY, to help mark things a little better, he’s some extra Blue Peter gold to mark the occasion, with huge thanks to Paul R Jackson for providing some extra-excellent knowledge.

WHAT DID THE BBC DO TO MARK BLUE PETER’S SIXTIETH ANNIVERSARY?

There was a special programme. Well, kind of. On 16 October 2018, BBC Four broadcast a special documentary on the history of the programme, going out under the search-term-thwarting title BP Confidential. This aimed to reveal the “true character of those working behind and in front of the camera on Britain’s longest continuously running children’s programme”. The programme blurb suggests it covered much that is already known about the programme (at least if you’re me, and you’ve just spent ages reading through published histories of the series), but it’s nice to see that it took the time to mark the work of Anita Ward, the previously-forgotten BP presenter.

This was just the opening act on a midweek BP tribute night, followed by Blue Peter: It’s a Dog’s Life (“the story of Blue Peter’s fondly remembered canines”), Blue Peter Flies the World: Morocco (a repeat of an international jaunt from 1968) and The Biddy Baxter Story, a profile of BP’s redoubtable editor.

WHAT ABOUT THE FORTIETH ANNIVERSARY?

Now you’re talking. Of course, the BBC being the BBC, BP Confidential wasn’t a new programme put together to mark the 60th – it had originally aired on Saturday 10 October 1998 on BBC Two, to mark the 50th anniversary, before being repeated on 9 December 2017 (also on BBC Two).

The 1998 celebration was part of a much higher-profile Blue Peter retrospective, with an entire evening of BBC Two celebrating the series. Ah, theme nights. I can’t be alone in really wishing BBC Two would run a theme night celebrating theme nights of the 1990s.

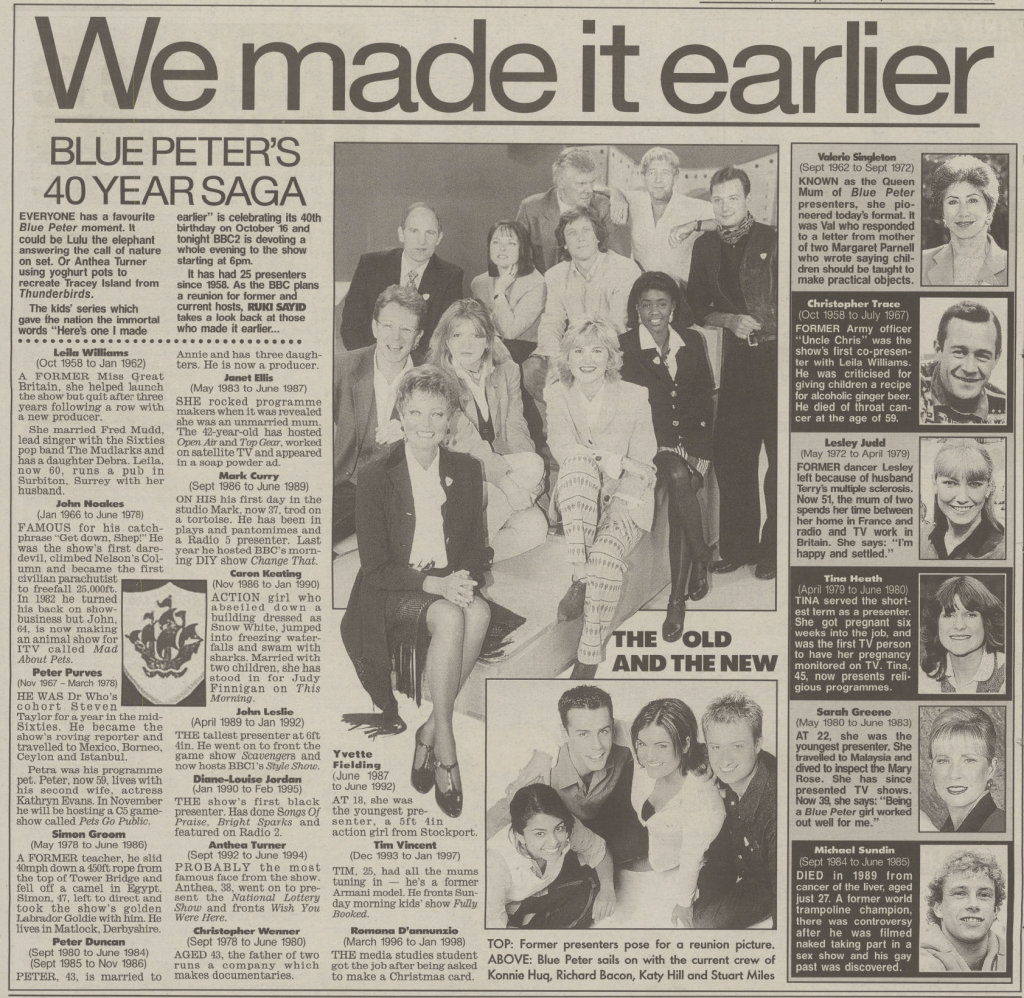

Daily Mirror, Saturday 10 October 1998 This kicked off at 6pm with Hello Again!, where former hosts John Noakes, Peter Purves and Valerie Singleton introduced themselves as our hosts for the evening. This was followed at 6.05pm by Carry On Blue Peter, a compendium of cock-ups from the programme, hosted by Richard Bacon, Katy Hill, Konnie Huq and Stuart Miles.

It being the late-90s, no programme could go long without having a phone poll, and Blue Peter Night was no exception – a poll being ran at around 6.30pm where you could spend 10p a minute voting for your favourite Blue Peter decade: 60s, 70s, 80s or 90s. The first hour was rounded off by It’s a Dog’s Life (as above, “the story of Blue Peter’s fondly remembered canines”).

But, as Brian Butterworth would say, that’s still not all. Following a break for news, sport, Chris Patten’s East and West, What the Papers Say and a documentary about the Cold War called, erm, Cold War, we were back at 8.55pm, with a rare excursion across the watershed for the Blue Peter ship. The late evening saw Spoof Peter at 9pm, a collection of BP pisstakes, featuring (it’s safe to say) Monty Python’s Flying Circus and Not the Nine O’Clock News. That was followed at 9.20pm by BP Confidential (see above), then at 10,15pm A Right Royal Reunion, where Princess Anne (Britain’s rural royal) recalled moments from her 1971 trip to Kenya, as catalogued by the series at the time.

Then, completely and brilliantly unsuitably, the ‘Murder at Tea Time’ episode of Murder Most Horrid that definitely shared a few similarities with the good ship. Then phone poll results, and bedtime.

A cracking evening’s telly, and no doubt.

[EDIT: And only slightly spoiled by the News of the Screws posting a certain exclusive about presenter Richard Bacon just eight days later, leading to an episode of Blue Peter memorable for all the wrong reasons. Thanks to Simon Tyers on BlueSky for reminding me of that near-coincidence.]

WHEN WAS THE FIRST APPEARANCE OF THE BLUE PETER BADGE?

On 17 June 1963, as famously designed by Tony Hart. Hart himself appeared as contributor to the series between 26 March 1959 and 15 July 1963, and presented the programme on at least one occasion (on 13 November 1959).

Thus, a cultural icon was born. WHAT OTHER NON-CANON GUEST BLUE PETER PRESENTERS WERE THERE?

Aside from Tony Hart, there was Ann Taylor (alongside Christopher Trace on 17 September 1959), Sandra Michaels (who replaced a holidaying Val Singleton between 20 and 27 April 1964), 11-year-old competition winner Ryan Gilpin (on 15 October 2003), Angellica Bell as stand-in host for Barney (for three months in 2016), Lauren Layfield on 27 May 2022 and YouTuber/TikTokker Joel Magician in August 2022.

WHICH FORMER BLUE PETER PRESENTERS WERE AWARDED A GOLD BADGE?

Please note: This doesn’t count Twenty of the forty former BP presenters have been handed coveted Blue Peter Gold Badges. And they are, with names in bold where badges were awarded after they left the programme:

Valerie Singleton (in 1994), John Noakes & Peter Purves (on 7 Jan 2000), Simon Thomas (on 25 April 05), Liz Barker (10 April 06), Matt Baker (26 Jun 06), Peter Duncan (20 Feb 07), Konnie Huq (22 Jan 08), Gethin Jones & Zöe Salmon (25 Jun 08), Andy Akinwolere (28 Jun 11), Helen Skelton (26 Sept 13), Barney Harwood (14 Sept 17), Janet Ellis (11 Nov 17, on an episode of BBC Breakfast), Radzi Chinyanganya (18 April 19), Lindsey Russell (15 July 21), Adam Beales (15 July 22), Lesley Judd (19 Oct 22), Richie Driss (3 March 23) & Mwaka Mudenda (29 Sept 23).

AND WHICH ONES WEREN’T?

There are nine notable omissions to the list: Leila Williams, Simon Groom, Sarah Greene, Mark Curry, Yvette Fielding, Diane-Louise Jordan, Tim Vincent, Stuart Miles and Katy Hill

Seven others have yet to be awarded a golden gong: Anita West, Tina Heath, John Leslie, Anthea Turner, Romana D’Annunzio, Richard Bacon and Joel Defries.

Four gold-badgeless Blue Peter presenters have since died: Christopher Trace, Christopher Wenner, Michael Sundin and Caron Keating.

Paul has been in touch with current Blue Peter editor Ellen Evans, who reported that she was aware of those omissions, so hopefully at least Leila Williams might yet get some welcome recognition for spell on the BP gangplank. Fingers crossed, anyway.

Actually, let’s hope it’s in that giftwrapped box.

Again, a (purely notional) Broken TV Gold Badge to one-man fact mine Paul R Jackson for those splendid nuggets of knowledge. Next update to the BBC 100 list soon!

-

“I Don’t Care Where That Tiger Cub Goes, Follow It!” – The 6th Most Broadcast BBC Programme of All-Time

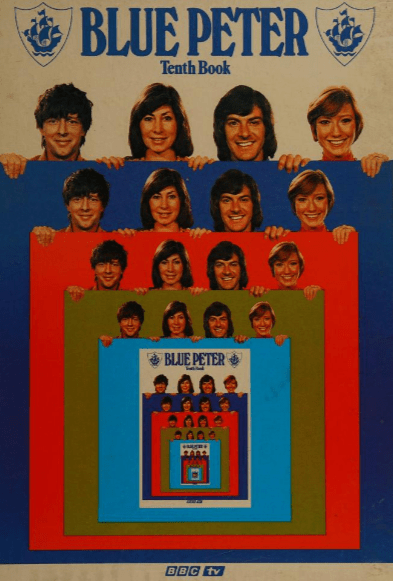

Back again, finally. Following a programme where it was quite honestly a struggle finding a lot to write about (Bargain Hunt, in case you’ve forgotten) to one where I could’ve spent about sixty years writing about it. And did actually spend very nearly that long digging out a complete broadcast history, such is the way Radio Times covered Children’s BBC listings for much of the 80s and 90s. So, non-specific brand of sticky tape to hand, try not to burn your house down with your tinsel, wire hanger and lit candle advent crown, and settle down for…

6: Blue Peter

(Shown 5951 times, 1958-2021)

Okay, let’s get it all out of the way: here’s one I made earlier, sticky-back plastic, get down Shep, Richard Bacon’s nostrils, Joey Deacon, marvellous knockers, tedious edgelord stand-ups on clip shows pretending they laughed when the garden got vandalised, and an elephant doing a big ol’ poo on the studio floor. Me foot!

While it might not exactly have been Tiswas (indeed, on an episode of Room 101, Nick Hancock dismissed it as “Oh no! More school!”), there can be little argument that it’s a quintessentially British piece of kids’ TV that ultimately meant a lot to generations of children. Even if for many, the main thing that it meant was “What’s on Children’s ITV?”.

Everything was so different when Blue Peter was originally piped aboard the HMS Television in October 1958. Sandwiched between a mid-afternoon closedown (preceded by Quick and Easy Dressmaking: 1. Jacket with Hood) and “exciting film series about the Fifth US Cavalry” Boots and Saddles, S1E1 of Blue Peter arrived with the modest descriptor “Toys, model railways, games, stories, cartoons: A new weekly programme for Younger Viewers, with Christopher Trace and Leila Williams”. That seemed to be a lot to pack into the modest fifteen minute slot it was afforded.

A relatively common assumption seems to be that erstwhile BP editor Biddy Baxter created the series (Baxter herself begins her written history of the show dismissing that very notion), but at that time she was still busying herself producing sound effects for radio drama. The original producer of the programme was actually John Hunter Blair, who was given a mission by Head of Children’s Programmes Owen Reed to come up with a format designed to appeal to five- to eight-year-olds. That particular subset of inbetweenies were deemed too old to still be watching With Mother, but too young to find any appeal in proto-yoof magazine programme Studio E.

John Hunter Blair, either taking a photo or closely examining part of the Hornby RS.6 Diesel Goods Train Set On paper, Hunter Blair seemed unsuited to coming up with such a format. Single and childless, the eccentric Hunter Blair preferred loftier pursuits such as composing operas and learning to speak various languages. However, he was armed with a wide range of knowledge on hobbies and interests that had entertained himself during childhood, and as an adult was keen to share his infectious enthusiasm with children. He had a particular affinity for model trains, to the extent that his office at the BBC hosted an intricate layout for his 00-gauge models, which he’d routinely play with while coming up with programme ideas.

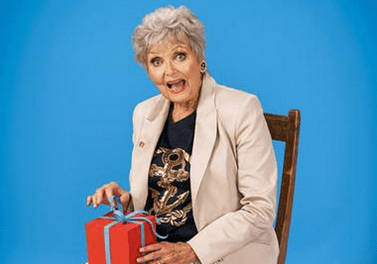

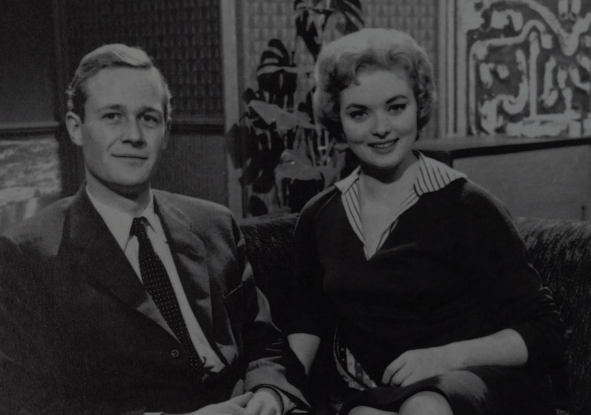

Hunter Blair’s fondness for all things Hornby certainly helped when it came to finding half of the original hosting duo. Actor Christopher Trace shared that enthusiasm, and spent the entire interview for the forthcoming hosting role playing model trains with his interviewer. The other hosting role was filled by Leila Williams, former Miss Great Britain, former host of Six-Five Special and who’d once taken advice from Frankie Vaughan to work on disguising her Staffordshire accent if she wanted to break into the world of showbiz. And who, going by the tabloids of 1959, once dumped Robin Day to start going out with Fred Mudd of the Muddlarks instead. Who she’d go on to marry, so fair enough.

Williams (left) was picked as Miss GB in part by Lord Bob Monkhouse, who then went on to denounce the whole enterprise, but who probably didn’t hand back the appearance fee (Mirror, 30 Aug 1957). For a title that would go on to (arguably) become more famous than any other in the history of British kids’ TV, the process of picking out the title ‘Blue Peter’ was similarly relaxed. As Biddy Baxter recounts the events in her book on the series (Blue Peter: The Inside Story), an early meeting between Leila, Chris and John included the editor musing that “Blue Peter would be a good name for the programme”. When asked by Leila what that title meant, John mused that “blue is a child’s favourite colour, isn’t it?”. What about ‘Peter’, asked Chris. “Peter is the name of a child’s friend, of course”, came the reply. Pub? Pub. It didn’t hurt that it happened to share the name of a flag raised by a ship before leaving port, tying in nicely with the programme’s quest to set sail on the sea of adventure.

Of course, all things in moderation. There was only a fifteen minute slot to fill, after all. And as such, the most action-packed part of early editions was the footage of a three-masted schooner running the titular flag up a pole in the title sequence. Once that starter was out of the way, a more sedate studio-based approach comprised the main course, often involving Leila playing with dolls and a besuited Chris mucking about with trains. Not the worst job in the world, of course, but not quite matching the vicarious glamour of Trace’s one-time role as stand-in for Charlton Heston in Ben Hur. Which isn’t a bad thing to have on your CV when you’re acting as surrogate Cool Older Brother to the nation’s children, of course.

Time would change that. Within a few years, the runtime extended from fifteen to twenty minutes, then twenty-five minutes (or occasionally longer if there was a sizeable gap in the schedule). The dolls and model trains were put back on the shelf, and livelier segments were brought in. On such occasion saw a lion cub brought into the studio, which turned out to be far less sedate than planned – the cub’s boisterousness causing lacerations on the arm of its handler while an unflappable Trace kept the interview under control.

While in Chris Trace and Leila Williams, the programme featured a pair of spritely young things, were in front of the camera, that wasn’t quite as true behind it. Showrunner John Hunter Blair suffered from a heart condition, and a couple of years into the show’s run that suffering increased, until one day he was no longer able to make it to his office-slash-playroom. While recuperating away from the BBC, a series of temporary producers stepped in, many armed with fresh ideas for the fledgling series. These weren’t always good ideas – the notion of having the programme alternate between “boy’s week” and “girl’s week” on a weekly basis – just ensured half the audience switched off each week.

Another grand folly led to the departure of original host Leila Williams, due to producer Clive Parkhurst basically failing to come up with anything for her to do. It wasn’t didn’t seem to be down to any lack of adaptability on Williams’ part – she’d proved perfectly adept at the role, and aside from BP was taking on small film roles and had recently featured in early ITV talent show Bid For Fame. And yet, Williams found herself dropped from several editions of the programme, before leaving on a permanent basis in November 1961. Not that this hampered Williams’ career entirely – she would go on to feature in several other programmes across ITV and BBC, such as hosting the BBC’s primetime vaudeville revival special Kindly Leave The Stage, and a judging role in excellently-named ice dancing competition Hot Ice and Cool Music, alongside a series of minor film roles.

By now, Blue Peter was suffering. Remaining host Chris was left to front the programme alone, and a queue of interim producers wasn’t going to improve the situation any time soon. With it eventually becoming clear Hunter Blair was unable to return to save the ailing programme, the call went out for a new permanent programme editor. And, to the surprise of many, the role was given to an aspiring young producer who a few years previously had been producing – yes! – sound effects for radio drama.

Biddy Baxter was tasked with transforming Blue Peter, but before that could begin she had to see out the remaining three months of her contract with BBC Radio, so experienced drama producer Leonard Chase was recruited to steady the ship for a spell. Immediately seeing the potential for improvement, Chase leant heavily on the factual aspect of the series, straying far from the original remit of “toys, model railways, games, stories, cartoons” and focused on a more wide-ranging view of what might interest the young audience. But there was still the problem of relying on Chris Trace to largely manage the on-camera action on his own.

Anita West: The (almost) forgotten BP presenter. The search for a new co-presenter was on. An audition was set up where each of four candidates would accompany Christopher Trace in reading a story, completing a Blue Peter make and interviewing a guest. The winning candidate turned out to be Anita West, actress, wife of Goon Show band leader Ray Ellington and mother to two young children. Her first appearance on the programme was alongside regular guest (and infrequent BP guest-presenter) Tony Hart, who would help settle her anxiety when carrying out her initial on-camera makes, until her confidence grew. It seemed sure that she would be a hit with the audience.

Sadly though, problems with her marriage led to a crisis of confidence – in an age where newspapers were fast becoming scandal sheets, any drops of blood in the water would surely have Fleet Street hacks sniffing around her private life. Despite that, West managed to keep her problems well away from her Blue Peter role, performing so well on screen she would soon be offered a full-time contract (a contrast from Leila Williams, who’d only ever been offered month-to-month contracts), along with the offer of working as an announcer at BBC-tv. The production team found themselves taken aback when the offer instead led to West offering her resignation, her tenure on the programme lasting just four months. A replacement co-presenter was needed, and quickly.

The problem was solved with the introduction of a dark-haired, serious and decidedly striking young new host. Valerie Singleton, had been another of the auditionees a few months earlier, losing out on the role to Anita West, but she immediately proved a more than capable presenter. Indeed, her straight-laced manner proved to be a key ingredient the programme had been missing. Her unflappable, authoritative and direct manner proved a suitable counterweight to Trace. Singleton was the cool teacher to complement Trace’s cool big brother mannerisms.

However, from October 1964 the programme began going out on Thursdays as well as Mondays, doubling the workload of the two-hander presenting team. As a result, with Trace pointing out that he as “bloody knackered” (presumably off-screen), a third member of the presenting line-up was added in 1966. Step forward John Noakes.

Step forward, but very carefully. Trace was still very much the main man, however. The programme’s first two summer assignments – Norway in 1965, Singapore and Borneo in 1966 – focused on the former actor. However, with Trace suffering from vertigo, new boy Noakes soon became the designated action man for the series. Christopher Trace left the programme in 1967 (much to the dismay of Huw Wheldon, who reportedly – if incorrectly – exclaimed “there will be no Blue Peter without Christopher Trace”) to move behind the scenes at feature film production company Spectator. That move failed to work out, but Trace would subsequently make the move to reporting and presenting Nationwide amongst other gigs, plus he’d often take the time to phone the Blue Peter production office whenever he came up with a potential programme idea.

Trace’s departure led to more prominence for John Noakes. His role on the programme had come about almost by chance. Biddy Baxter was flicking through the local newspaper while visiting her parents in Leicester, and happened across a theatre review raving about local rep player Noakes, which mentioned his history working as an engineer on DC7s at BOAC. At ease in front of an audience? A day job that involved mucking about with very real aeroplanes? Someone certainly worth meeting in person, with the need for an addition to the BP hosting roster.

Not that there had just been a handful of candidates. On his arrival at TV Centre, Noakes was fiftieth in the queue to audition for the role. He was more than a little nervous, having only appeared on stage in character before, never having had to appear as himself, nor on national TV. On top of that, he was starting to feel disillusioned with the whole performing lark anyway. Despite all that, the nervous energy displayed by the then-31-year-old won over Baxter, and he was handed a three-month contract to join the series from late December 1965.

While history seems to have pegged him as the avuncular figure hosting Go With Noakes alongside canine companion Shep (as well as for breaking down when interviewed about Shep’s passing on BBC1’s teatime infoblast Fax! in the 1980s), his tenure was as action-packed as any in his thirteen years on the programme. Clambering up the mast of the HMS Ganges, setting a record for highest civilian free-fall parachute jump, clattering his way down the Cresta Run and (as pictured above) going full Fred Dibnah while climbing Nelson’s Column. He truly was the programme’s first true Man Of Action.

Noakes would be joined a few years later by Peter Purves, a one-time Doctor Who companion (Steven) who was subsequently too typecast to land any decent acting role after stepping out of the Tardis for the last time. His luck changed on being interviewed for the Blue Peter role, and it didn’t take long to decide he was the man for the job. Before he could get into the lift at Television Centre following his audition, Biddy Baxter and Rosemary Gill collared him and offered him the gig on the spot. He initially planned to stay for six months until more offers of acting roles reached his inbox. He ended up staying for almost thirteen years.

With the three saints of Peter on board from 16 November 1967, the programme’s first true imperial phase could begin. Little wonder that, in his marvellous book covering his personal history of the programme, future programme editor Richard Marson referred to the trio as “unquestionably the most famous presenting team in the show’s history”.

14 September 1970 saw another landmark in the history of the programme – the first ever colour edition of Blue Peter. That change could have come about even earlier – Monica Sims, then Head of Children’s Programmes, contacted BBC-1 Controller Paul Fox about getting some extra funds for the series so that the programme’s summer jaunt could be to somewhere a little more exotic than Cornwall, in keeping with the adventurous excursions from previous years, especially now there was the prospect of the film being broadcast in colour. Fox relented to be main request, but denied the request for the expense of shooting in colour. That decision led to disgruntlement from Fox in 1971, when repeated footage of 1969’s trip to Ceylon could only be broadcast in monochrome on the now multicoloured BBC1. The programme had more success with shooting in colour in May 1970, with director John Adcock being permitted to try out colour film for a trip aboard the QEII. That was just a test – the film itself was broadcast in black and white, but it proved that it could work, and that the programme could make the move into full colour.

Imagine only getting to see this in black and white. However, the upgrade came with conditions attached. Only the larger studios within TVC were equipped to cope with broadcasting in colour, and those weren’t always available to the programme. Whenever circumstances dictated Blue Peter move into a smaller studio, it was accompanied by a move back into monochrome. This meant it took until June 1974 before the blues of ‘Peter could be enjoyed on colour receivers on a permanent basis. As a result, those with expensive tellies certainly got to enjoy a much more immersive experience with BP’s summer sojourns, starting with July 1970’s trip to a Mexico still buzzing with excitement from the previous month’s World Cup.

Another new introduction to the programme came about in March 1974, with the official unveiling of the Blue Peter Garden. Up until that point, the programme had been keen to utilise every spare bit of space in Television Centre, the big studio doors often being flung open to permit everything from vehicles to marching bands, but other programmes and occasions often called for use of that space, leaving Blue Peter locked indoors. BP often made use of the TVC car park, or the infamous TVC Doughnut, but those areas couldn’t be guaranteed to be available to a live programme. Far better to have a little bit of space that was very much the programme’s own safe space – specifically a secluded patch of land in front of the BBC restaurant block.

It had previously been pressed into use for programme segments in the past, but only really on an ad-hoc basis. Now, ‘inspired’ by their ITV rivals Magpie having their own smallholding at Teddington Lock, the patch of land was to become to sole preserve of Blue Peter. Now, tower block kids around the UK could be afforded their own surrogate set of flower beds, fish pond and – a little later – an Italian-style sunken garden.

As the programme prepared for the 1980s (aided by a new version of the theme tune composed by Mike Oldfield, above), a new presenting line-up evolved. As the new decade arrived, the team of Simon Groom, Tina Heath and Christopher Wenner didn’t quite enjoy the popularity of the familiar line-up of the previous decade (Lesley Judd having replaced Valerie Singleton in 1972 following the traditional presenter overlap), and the latter two-thirds of the team didn’t hang around for too long. Luckily, a much hardier troupe of presenters was about to provide a sense of solidity to the curved couch. Sarah Greene arrived in May 1980, while Peter Duncan joined the team that September. Each had previously appeared on screen in acting roles – Duncan in the likes of Space:1999 and Play for Today, Greene in ITV’s compelling housing association soap Together – but both slotted into their new presenter roles with ease.

It certainly helped that the series seemed keen to cover technological advancements of the 1980s, which was certainly a boon to any children-of-the-80s who’d pore over the electronic gizmo pages of their mum’s Kay’s Catalogue. Astonishing space-age achievements covered by the series included the first ever transmission of a fax message on British TV (sending a picture over the telephone line? Witchcraft, surely. If memory serves, it was a scribbled drawing of a brolly and some raindrops), plus a departing Tina Heath introducing viewers to the concept of ultrasound technology with a live broadcast of her baby scan.

1988 saw the end of an era for the series, with long-time programme editor Biddy Baxter leaving the series after more than 25 years at the tiller. Baxter wrote about the experience of finally letting go in the introduction to her own Blue Peter: The Inside Story book:

In the gallery, my stomach lurches — just as it had lurched every Monday and Thursday for twenty-six years. That special frisson peculiar to all live broadcasting when it’s the point of no return — no second chances or second thoughts. Will the presenters achieve that peak of perfection we’ve been striving for all day? Will the studio director make a particularly tricky effects sequence work? Will Rodney on Camera One be okay with that difficult tracking shot? He’s a genius, so if anyone can make it work, he will. BUT…

Considering that at least thirty people have the chance to make or break each live Blue Peter transmission, it’s amazing that the disasters are so few. Come the crunch, when it’s live there is that extra adrenalin flowing and an extra camaraderie that, nine times out of ten, creates pretty nearly what you’ve hoped to achieve. When the disasters happen they’re usually mega ones, like a telecine machine playing in an eight minute film breaking down at the beginning of the reel — on a day when there’s no back-up on video. Or a cheerful chap in a brown coat walking into the studio during transmission clutching a large black plastic sack and yelling: “Let’s be having you then, where’s your rubbish?” Or the anonymous engineer deep in the bowels of Television Centre pulling a vital plug that disconnects the large, motorised camera taking the most important shots in the whole programme.

But today the lurch was worse. It was my very last Blue Peter. ‘There was a large chunk of the programme completely unknown to me. I hadn’t written the script, I hadn’t even been allowed to see it. Lewis Bronze, Blue Peter’s talented assistant editor for the past five years, had been quite firm. “It’s your last programme and you’re going to be in it. Don’t worry, leave it all to me, just sit back and enjoy it!”

Biddy Baxter, Blue Peter: The Inside Story (Ringpress Books, 1989)Ultimately, Bronze’s gambit certainly helped to quell any sadness on the part of Baxter as she prepared to leave the show. Any despair was swiftly reduced by the fear of appearing in front of Blue Peter cameras for the first time. By the end of the programme, she’d been coaxed down from the gallery, welcomed on-set, shown with a montage of programme highlights, given a large album of photos from her BBC career and presented with a prized a Gold Blue Peter Badge. The latter award was the very highest honour the programme would go on to bestow, putting Baxter in the same league as Paul McCartney, Steven Spielberg, Madonna, Sir David Attenborough and The actual Queen.

The late 80s and early 90s saw the programme start to make more of an effort to cover environmental issues – quite a change from those early years when anything emitting exciting plumes of diesel would have been deemed a suitably thrilling candidate for coverage. This period even saw the introduction of a green Blue Peter badge for environmentally-adjacent achievements.

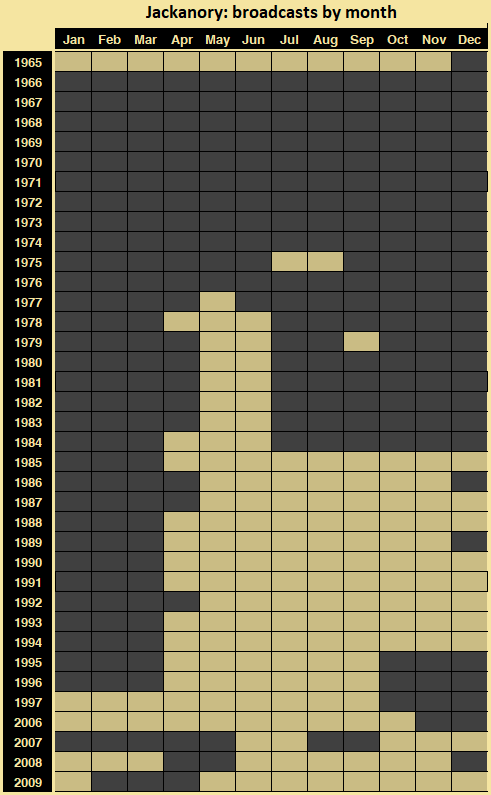

From 1995, a third weekly edition of the programme was introduced, albeit a more fun~based edition of the programme airing in Fridays (usually between autumn and early spring months), concentrating more on things like celebrities than sea scouts. Whether the increased demands of an extra show were a factor or not (though by this point some episodes were pre-recorded), the turnover of team members increased during the 1990s. Though despite that, Konnie Huq (having joined in December 1997) would go on to become the third-longest serving BP presenter of all-time, clocking up just over ten years on the series. And, in fairness, it’s not as if presenters from the 1980s had a habit of hanging around for too long, as the following did-it-purely-because-I-could table of data shows:

No, this was a valuable and productive use of my time. Despite a revolving door of presenters during this spell, it wasn’t all grim during this spell for the series. It became one of the first BBC shows to land its own section of the bbc.co.uk website, and the programme warranted a pair of summer prom concerts. However, each spell of sunshine is followed by a little rain. Or, erm, snow. Yes, I do mean Richard Bacon getting the boot for being caught in the midst of nose candy. Don’t think that was mentioned in that year’s Blue Peter book.

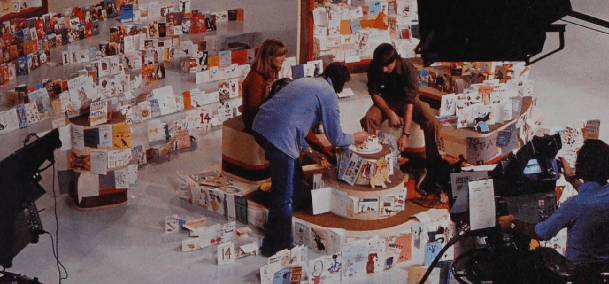

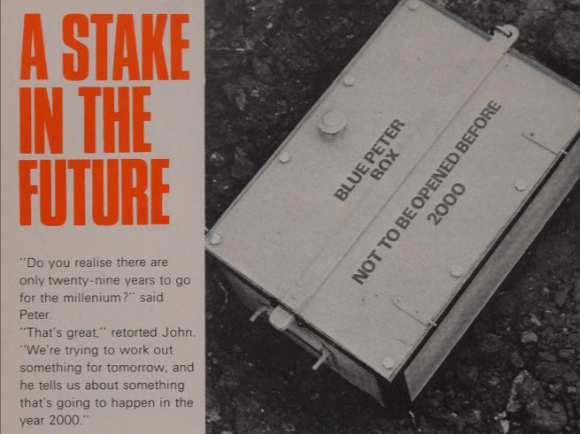

One of my favourite follies is the concept of the time capsule, and Blue Peter had been very much a part of this. The 1970s incarnation of the series had buried one back in the day, and with the arrival of space year 2000, it was time to dig it up. It must gave seemed such a distant future at the time, but in the event the BP Dream Team of Singleton, Noakes and Purves were still around to help dig it up. The fact the contents were in a worse condition than if they’d just bought each item off eBay only detracted from the achievement slightly. Honest. And it was fitting that the old team made a reappearance at the time, as with Konnie Huq, Simon Thomas and Matt Baker now on the sofa, the current generation of viewers has their very own stable team of presenters to call their own.

The burial of the Time Capsule was covered in 1972’s Ninth Blue Peter Book.

And again in 2000’s Thirtieth Blue Peter Book With Friday editions now commonplace, there was still a summer-sized gap in the programme’s broadcast calendar. That changed in 2001, when the addition of twice-weekly episodes during July and August saw the programming running throughout the year for the first time since 1965. The brand was extended further still following the arrival of Richard Marson as programme editor in 2003. With the something needed to fill the digital bits that made up the new CBBC channel, same week repeats of the regular Blue Peter show were joined in the schedule by spin-off series Blue Peter Unleashed from February 2002, that first episode promising “football with Steven Gerrard, speed boats, stuntmen, billiards and rock climbing”. That was joined later that year by Blue Peter Flies The World, which collected together trans-global reports from the programme.

As viewers gradually migrated to the new CBBC channel, viewing figures for the series on BBC One began to slide. By this point, a reduction in the programme’s budget had already seen it relocate to a smaller studio, and now it was being shimmied into a slightly less glamorous slot in the schedule – bumped back to 4:35pm from February 2008 to free up the post-Newsround slot for The Weakest Link.

A few years later, as 2012 drew to a close and with the UK’s digital switchover having completed in October of that year, it was decided that children’s programming no longer needed to be broadcast on BBC One. After all, any TV set now had access to the CBBC and CBeebies channels, meaning more room for programmes about buying houses and antiques on the Beeb’s flagship channel. And so, on Friday 30 November 2012, a regular episode of Blue Peter aired on BBC One for the last time. By this point, first run episodes of the programme were already going out on CBBC, so it’s hardly a surprise the berth on One was being given to something else. But at least that last regular appearance on the channel was something typically Blue Peter: as part of Children’s Commissioner’s Takeover Day, a quartet of competition winners were afforded the chance to produce the episode.

That wasn’t truly the end of the programme on ‘regular’ BBC channels, however. 20 October 2018 saw a BBC Two airing of Blue Peter’s Big Sixtieth Birthday, an hour-long special where former presenters returned to the studio to help the current team celebrate TV’s most storied children’s programme. Following that, occasional episodes of the series would get repeat broadcasts on BBC Two on Saturday mornings, though one suspects that was down more to needing something to fling into the schedule than anything else.

While the programme has – as one might expect – changed beyond all recognition during six-and-a-half decades on screen, so much so that it’s only been generating one episode per week since 2012, it’s comforting to know it’s still there. Even if at one stage, BBC Children’s Controller Richard Deverell decided that the programme should become “more like Top Gear”. Ew.

However, with the future of the CBBC channel in doubt – at the time of writing it’s due to be given the chop as a standalone channel (alongside BBC Four) in 2025, with all content becoming iPlayer-only from that point on. Will Blue Peter survive the cull? One can only hope, but even if it doesn’t, that’s one hell of an innings.

Phew, that was a long wait. Especially as I’ve hardly scratched the surface of the sixty-five years it’s been running for. Still, I’m sure the next entry on the list will be much easier to write about… oh. Sigh. See you soon!

-

“Bobby Dazzler” – The 7th Most Broadcast BBC Programme of All-Time

Nearly at the last half-dozen!

7: Bargain Hunt

(Shown 5843 times, 2000-2021)

Some game shows try everything they can to ramp up the excitement. ITV seemed to go big on this concept in the 1980s, the network clearly at the zenith of the Licence To Print Money Years. This saw shows such as Ultra Quiz, which would see a group of contestants around the world for a series of themed trivia questions, Run The Gauntlet, which saw teams from each of the home nations battle for supremacy in races using jet skis, quad bikes and the like, or Interceptor, a thrilling concept from the team behind Treasure Hunt that was basically a county-wide game of laser tag. All programmes I loved as a kid, and yet they each had very short shelf lives. After a few years, the Ultra Quiz budget was dropped to the extent David Frost was swapped for Stu Francis and New York swapped for Bournemouth. Interceptor lasted for a single series and despite being deemed popular enough for a spin-off videogame in 1989, Run the Gauntlet nowadays doesn’t even warrant an entry on Wikipedia.

Teams leaping out of helicopters at the start of the first event not exciting enough for you, Wikipedia? Eh? If you want longevity for your game show format, dampen down the excitement quotient a bit. So much so, it’s arguable whether it even warrants a place in the game show genre. Such as the next programme on our list. Recently clocking up its 66th series (vidiprinter: sixty-six) Bargain Hunt tasks a pair of teams (“Red” and “Blue”) with spending a set sum of money on trinkets at an antiques fair, with each having an expert on hand to offer advice. Once the trinkets have been bought, they’re put up for auction, and the team who make the most profit on their original outlay (or the smallest loss) are declared the winners. And… that’s it. No lasers, no helicopters, and any explosions can purely be considered coincidental.

Originally, each team budget was set at £200, and teams could buy as many or as few items as they desired. This was subsequently limited to just three items, presumably to avoid instances of participants buying dozens of items and boring everyone solid at the auction stage. Later on, the budget was upped to £300, and an option of swapping one of their items for an alternative trinket was introduced. This was tweaked further in series 14, allowing for a ‘bonus buy’ to take place with any surplus budget. And that’s pretty much it.

The series came about in 1999, with David Dickinson at the helm. By this point, Dickinson’s TV career had only been a few years old, but his new career trajectory had been much steeper than most. It was something the antiques expert had fallen into following a barbecue at his daughter’s house, where he got chatting to her next door neighbour. That neighbour happened to be Alistair Much, co-owner of a TV production company, who was taken by Dickinson’s resemblance to Ian McShane’s fictional antique roustabout Lovejoy. By happy coincidence, Much was working on pitching a new series on antiques to broadcasters, and thought his brand new pal might just be a perfect participant for it.

In the end, the networks failed to express any interest in that particular series, but Dickinson would go on to feature in an episode of BBC2 documentary strand Modern Times, produced by Much, and looking at – of course – some of the characters within the world of antiques. Dickinson would be the standout figure of the episode – his Lovejoyesque appearance also remarked upon by The Independent’s TV listings – and his personality certainly seemed to resonate with those in the TV industry. Dickinson was plucked to present a Buyer’s Guide segment in BBC Two series The Antiques Show (1997-98), which swiftly led to a pilot of his first solo vehicle (Under Your Nose: a show looking at items “worth a bob or two” lurking in the homes of unsuspecting members of the public, which Dickinson’s autobiog says was broadcast, but which Genome says wasn’t).

[EDIT: Thanks to Daniel Webb for letting me know The Duke did in fact record a different pilot around this time. Swap Until You Drop saw Dickinson team up with A Certain Disgraced Former It’s A Knockout Host and John Fashanu for a competitive swapping roadshow, refereed by Mary Nightingale. This aired once, on Friday 2 April 1999. On top of that, it seems the pilot he was talking about was chopped into bits and used in consumer show pilot Money For Old Rope (BBC One, 7pm 6 Jan 1999), which included a segment where “antiques expert David Dickinson uncovers a few treasures in the homes of three neighbours“.]

His next gig was a little more glamorous, becoming a regular reporter for Holiday in 1998, whisking him off to destinations from Milan to Devon on early evening BBC One. Dickinson’s star was certainly in the ascendancy at that point, with a starring primetime role in C5’s The Antique Hunter. While it made for some memorable segments in early episodes of TV Burp (“I am the Hunter!”), Five honcho Dawn Airey decided a second series wouldn’t be forthcoming. However, a call from the BBC’s Mark Hill soon saw a return to the screen for Dickinson: a new daytime show called Bargain Hunt, airing from March 2000. And it was probably the personality of a man Terry Wogan once introduced as “Peter Stringfellow crossed with a mahogany hatstand” that did more than anything to attract an audience to the programme, with his chipper attitude and occasional asides to camera proving popular.

Before long, that growing attention saw Bargain Hunt moving on up to the big time, and a peak 8pm slot on BBC One in August 2002. While it’s tempting to suggest this was down to a lack of inspiration on the part of the BBC, the ratings don’t lie. The first peaktime episode of Bargain Hunt drew an audience of 6.89m, and the end of that initial primetime run was followed by four episodes of spin-off Celebrity Bargain Hunt Live for that November’s Children in Need week. Stars such as Tony Blackburn, Dermot Murnaghan and Sarah Cawood took part, with any profits going to the charity, and viewing figures rose even further, peaking at 7.88m. That’s two million viewers more than watched Liverpool’s Champions League exit at the hands of FC Basel over on ITV. Take that, UEFA.

However, a daytime show thrust into the big leagues doesn’t often have the stamina to stick to the national consciousness for long, and that was the case for imperial phase Bargain Hunt. The programme slipped out of the BARB Top 30s for BBC One in late 2003, following a move to an Emmerdale-adjacent 7pm slot. A year later, the programme left the primetime schedules, with Dickinson duly leaving for pastures new (mainly reality series Dealing With Dickinson, which lasted for a single series before Dickinson decamped to ITV and his Real Deal). Luckily for Bargain Hunt ultras, the daytime version had remained a going concern throughout the show’s spell in the peak-hour spotlight, with presenter Tim Wonnacott at the controls, and that’s where he would continue.

Himself no slouch when it comes to antiques – before picking up the Bargain Hunt baton, his CV boasted a spell as director of Sotherby’s – the bowtied buff kept the programme on a steady tiller. Well, apart from one episode in 2010 where a musical bed of Mylo’s Drop the Pressure was used, with nobody on the production team noticing the lyric “Motherfuckers gonna drop the pressure” surviving the edit. Whoops. And that coming just a year after a track called “Horny Baby” by Dust Devil stopped being used as the programme’s theme music, too. Pure. Audio. Filth. (Okay, the latter was a light pop-jazz number. But still.)

That mishap aside, little of interest happened in the programme (as far as I’m quite selfishly concerned) until 2015, when an alleged altercation with producers saw Wonnacott initially suspended from the series, and subsequently stepping down. He would continue to serve as narrator for Antiques Road Trip and Celebrity Antiques Road Trip, so it wasn’t the end of the world for him.

Which explains why he’s clearly been too busy to update the design on his own website since 1999. From 2016 onwards, the programme would go on to be hosted by a rotating cast of antique experts, including Danny Sebastian from CBeebies’ Junk Rescue, Antiques Roadshow ceramics guru Eric Knowles and Flog It! alumni Caroline Hawley. Despite the addition of new faces front and centre of the programme, Bargain Hunt remained largely affixed to the formula that had served it so well since the dawn of the third millennium, with innovations like a ‘Big Spend Challenge’ and the ‘Presenter’s Challenge’ adding a mere sprinkle of change to the format.

2016 also saw the programme singled out by the press as an example to underline part of Culture Secretary John Whittingdale’s white paper on the future of the BBC, but it’s unlikely many members of the production team were high-fiving each other with excitement. The programme was being dragged out as an example of the BBC sorely lacking “greater levels of creative ambition”.

SPOILER: None of the above programmes were axed. Of course, it wasn’t remotely cancelled. In fact, Bargain Hunt will probably outlive us all. Hey, each passing year means another year’s worth of stuff becomes antique.

And occasionally, it still has the power to surprise us. Such as an episode in 2018 recruiting hip young indie gunslingers Jarvis Cocker (aged 54 at the time) and Bez (also aged 54), along with respective bandmates Rowetta Idah and Candida Doyle to take part in a pop-themed celebrity episode. What excitement could a quartet of fiftysomething NME darlings really bring to the programme, though?

How it started / How it’s etc. There’s life in the old dog yet, eh?

BONUS FACT! Bargain Hunt has been mentioned three times in the House of Commons, according to Hansard. And yet none of them was worth mentioning in detail here. How’s that for failing to clear a low bar?

There we go. That’s the final daytime property or antiques show on the list ticked off. All gold from hereon in. Or your money back.

-

“I might know someone who works on this and get punched on the nose”: The 8th Most-Broadcast BBC Programme Of All Time

And so, from Snooker, a sport that has had a relatively rich and varied history since the very birth of broadcasting, onto a programme that basically hasn’t changed since it began twenty years ago. Heeeeere’s

8: Homes under the Hammer

(Shown 5166 times, 2003-2021)

One thing that was always going to make an appearance in this list: property shows. Rivalled only by quizzes for the trophy of Genre Representing The Most Gapingly Open Goal In Daytime Programming, it’s a slight surprise we haven’t seen more of them on the BBC.

We’ve had Escape to the Country and To Buy or Not to Buy in the top hundred so far, while Changing Rooms is (slightly surprisingly) well outside the hundred (if anyone was anxiously waiting for it, you may now exhale). Such programmes are much more at home on Channel Four, which is something to ponder every time the channel boasts about how it strives to cater for underserved minorities, suggesting it only seems keen to serve minorities looking to improve their property portfolio by a restoring a château on the cheap.

Despite Four’s stranglehold on the genre, the Daddy of Property Programmes is very much a BBC enterprise. Originally hosted by Lucy Alexander and Martin Roberts, Homes Under the Hammer follows a number of properties bought up on the cheap via auction, and then follows the fortunes of the people who buy them, do them up, and then sell them on for big profits. It’s a staggeringly popular daytime programme. Which is why only seven programmes have been broadcast more often throughout the BBC’s entire history.

Despite that… very little seems to have been written about the programme. The first time it appeared on our screens in November 2003, no newspapers pulled it aside for a preview paragraph or two. Nobody seems to have written an article about it when it arrived. Even the Radio Times, given the programme’s 10am slot, only had room on that day’s listings to offer up “the weekday run starts by following three Devon properties that are up for auction.”

The Wikipedia entry for the programme isn’t even sure when some of the series started or ended, or how many episodes have been made.

As should hopefully be clear, I don’t use Wikipedia for research, but it’s always worth having a nose at. It’s a bit strange, to be honest. Sure, nobody’s starting a change.org petition to have a 4K BluRay remaster of the entire series, but it keeps going. Someone must do more than simply tolerate it? Surely?

I can’t help but suspect there’s a reason nobody seems especially keen to chronicle the history of the programme. And that reason is… in every single home under a hammer, in every single room, the cameras are having to keep the elephant out of shot. But we all know it’s there.

The point of the programme is to show homes being sold in a rush at knockdown prices. Often homes in need of repair, of modernisation, of rapid repairs to the damp course, cracked tiles or a leaky roof. For the purposes of the programme, that’s a good thing. An un-valuable home can be turned into a profitable house. The programme hardly shies away from this – the production company’s website sells the show as “the exciting auction series where potential bargains can bring big return on investment and a carefully planned house makeover can make all the difference”. How could anyone spending a morning off picking Coco Pops out of their beard miss out on something involving a big return on investment?

And yet: there’s generally a reason houses at auction are having to be sold so quickly, and so cheaply. And – SPOILERS – it ain’t due to a spate of benevolent property magnates who’ve just won the lottery and can’t be bothered waiting to dispose of their stock.

Daily Mirror, 7 Sept 1991 – an early use of the phrase “Homes Under the Hammer”. Not sure if that inspired the programme title or not. Given Britain is a place where an entire national identity has been built on Maximising The Value Of Your Property, someone quickly selling a home at auction probably isn’t doing it for the happiest of reasons. It might be that the previous occupant had died, and the grieving family want to sort the estate out quickly, granted. But when it comes to houses in poor states of repair, it’s more likely that someone – yes, very likely a family with children – had been struggling for ages to keep their lives together and finally had to admit they could no longer able to afford the place. It could even be that the decision to sell had little to do with them, and more to do with landlords or mortgage providers. All that’s clear is, in many of the households explored by the HutH experts, people’s lives had been taking place in most of the properties. And now they aren’t.

“And here’s where Susan shared the sad news with John that she’d been laid off from the bakery. Just next to the stairs leading up to the bedrooms.” (Reader’s Voice: “Maybe they moved out because of the elephant you mentioned? I wouldn’t want to live in a house where there’s an elephant!”)

Sigh.

Anyway, moral concerns aside, there’s something else I can’t help but notice about Homes Under the Hammer: it’s programme that offers a very handy grab-bag reference to (a) someone hoovering up cheap property for quick and easy profit, or (b) as far as its audience goes, it’s the epitome of indolent tele-viewing.

How do I know that? Because I’ve been looking to see how often it gets mentioned in works of fiction, that’s how. And so, here comes a rundown of:

THE TOP THIRTY TIMES ‘HOMES UNDER THE HAMMER’ HAS BEEN REFERENCED IN WORKS OF FICTION (AND OCCASIONALLY NON-FICTION)

Oh, we are very much doing this. Here goes. I could easily have made this a top fifty or more, easily. There are a lot out there. And this is just from those I found on the archive.org lending library. And remember, while several of the quotes below might be a bit on the punching-down side, at least they didn’t directly profit from a family’s eviction. Even the fact one of the quotes is from Mrs Brown’s Family Handbook doesn’t change that.

30: Finders Keepers, Belinda Bauer (2012)

“Steven’s mother, Lettie, took pills too. She sat on the sofa next to Nan, crying at Homes under the Hammer, with an old Spiderman pyjama top crumpled in her hands.”

29: Born Gangster, Jimmy Tippett, Nicola Stow (2014)

“There was nothing to do apart from watch crap on television, and I was sick of it. My days were revolving around Loose Women , This Morning, Homes Under the Hammer, Cash in the Attic, Deal or no Deal and The Price is Right.”

28: The Ex Factor, Eva Woods (2016)

“A raincheck meant, Never in a million years, sucker. A raincheck meant, I’ve met someone new but I am too chicken to tell you. Or worse, I just can’t be bothered to leave my sofa and Homes Under the Hammer is more appealing than another night in your company. Ani knew that better than anyone.”

27: Alan Stoob: Nazi Hunter, Saul Wordsworth (2014)

“With no idea what to do I turn on the telly and flick between The Wright Stuff, Homes Under The Hammer, Location Location Location, Antiques Roadshow and a 3-2~1 starring Dusty Bin. Footage of me running naked, tiny penis embedded in my scrotum, plays on ITV2. I switch off and shuffle into the kitchen. There’s a note from Tom.”

26: Our World, Little Mix (2017)

“I’ve got a cinema room with an L-shaped leather sofa and I love being in there, in jogging bottoms and a hoody, thick cosy socks, relaxing with a glass of wine. On TV I love Catchphrase – shouting the answers at the telly! – TOWIE, George Shore, And and Dec’s Saturday Night Takeaway. I’ll watch anything to do with property. Grand Designs, A Place in the Sun, Homes Under the Hammer.”

25: Survive in the Office With a Sense of Humour, Andy B and Jamien Bailey (2014)

“You filled out a really long application form that asked you like, loads of questions and stuff and made you look up the meaning of the word diligent. You dragged yourself away from ‘Homes Under the Hammer’ twice, for both a first and second interview.”

24: Consequences… I’m With the Band, Laurie Depp (2008)

“”Are you OK, Mum?” I asked, without expecting much of a response. She looked up at me slowly, as if trying to recognise who it was that had invaded her silence and the flickering of Homes under the Hammer on the TV screen.”

23: Mrs Brown’s Family Handbook, Brendan O’Carroll (2013)

“If they know you’ve been sitting with your feet up all day watching Homes Under the Hammer and doing the word snake in the back of the paper, they’ll be filling your day with their bollocks and then you’ve no time for telly-shopping.”

22: More Morello Letters, Duncan McNair (2011)

“Hoping you can re-house the old trout for us. She loves bingo and wrestling and a certain amount of horseplay. She also needs to be near a telly that’s showing either Terminator or Die Hard. Or Homes under the Hammer.”

21: Bonkers: My Life in Laughs, Jennifer Saunders (2013)

“Oh, please don’t let me be ill. . . I haven’t got time to be ill! I have no time to sit in hospitals! I have work and children and I want to do stuff and be in control of my own life, even uf that just means watching Homes Under the Hammer.”

20: Single Men, Dave Hill (2005)

“She saw that Lynda had obtained an A-level prospectus from the local sixth-form college and left it meaningfully on the coffee-table. Marie considered reading it but the booklet failed miserably to leap unaided into her hands so she watched Homes under the Hammer instead. She was just drifting, dribbling, gently off to sleep when her mobile rang.”

19: Quick Pint After Work? (and Other Everyday Lies), Luke Lewis (2014)

“Homes Under The Hammer: Daytime TV show that is only ever watched through a veil of tears, by those who are either unemployed, sick or depressed.”

18: How to be a Grown-Up, Daisy Buchanan (2017)

“During dark wallows, I have compared myself negatively to a woman in the middle of a paternity suit on Jeremy Kyle (“Two men are fighting over her! I have no one!’), to someone who’d just bought a house with chronic dry rot and a problem garden on Homes under the Hammer (‘I will never be a homeowner! Not for me the joy and pain of Japanese bindweed!’) and everyone on Loose Women (‘Urggh, I hate myself, they all have better hair than mel’).”

17: The Wish: 99 Things We Think We Want, Bill Griffin (2017)

“It’s so fraught it’s a wonder anyone bothers dating at all, when they could be home alone watching Homes under the Hammer and eating dim sum in their pyjamas, which is obviously preferable to sitting opposite a stranger in Pizza Express and asking them how many siblings they have.”

16: Between a Mother and Her Child, Elizabeth Noble (2012)

“Her life had become a dull routine, punctuated by television programmes. She watched far too much boring television, but their showing times and their theme tunes were the clock of her day. Homes Under the Hammer, Escape to the Country, Come Dine With Me and then Coronation Street.”

15: Hurrah For Gin: The Daily Struggles of Archie Adams (Aged 2¼), Katie Kirby (2017)

“Suits us all fine if I’m honest, as now we can just sit about in our PJs on Monday mornings – Mummy can watch Homes under the Hammer on the TV, I can watch Fireman Sam dubbed in German on her phone and Chase can just lie on her play mat sicking milk up and trying to work out how to roll.”

14: Watching War Films With My Dad, Al Murray (2012)

“Critics will say look at Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation series (which I’ve never seen), that was what used to be on BBC1. Now look at, say – and I have to be careful here, I might know someone who works on this and get punched on the nose – Homes Under The Hammer.”

13: The Unmumsy Mum, Sarah Turner (2016)

“That hour of tea and sympathy outside the house was priceless and gave me the much-needed motivation to get dressed and not stay indoors watching Homes Under the Hammer for the fifth consecutive day.”

12: Her, Harriet Lane (2014)

“I look down at Cecily, whose dark eyelashes are fanned out on her round cheeks, her fists curled on either side of her head. Her chest rises and falls in her moon-patterned sleeping bag: in, out, in. I visualise Peggy on the treadmill in pink velour joggers and a light sweat glaze, eyes locked onto Cash in the Attic or Homes Under the Hammer.”

11: Thinking About it Only Makes it Worse And Other Lessons from Modern Life, David Mitchell (2014)

“There’s my personal favourite, Homes Under the Hammer, where the production company has just set up a video camera at a property auction and sent presenters to stalk the successful buyers.”

10: Recipes for Life, Bernadine O’Connell (2011)

“She wears less lycra than I would dare on the beach. Hope she isn’t coming near me – keep my eyes focused on the monstrously large TV screen above and pretend to be engrossed in ‘Homes Under the Hammer’.”

9: The Pictures Are Better on the Radio, Adam Carroll-Smith (2016)

“At this point, I’m not ruling out the possibility that when Bob gets home, he is actually just watching a different game — Everton vs. Swansea or something — or maybe just episodes of Homes Under The Hammer, and wondering why West Ham aren’t involved and they haven’t shown a single replay of Seiko/Sakho’s goal.”

8: Christmas Kisses, Alison May (2016)

“Liam sat on the sofa. Homes under the Hammer had finished hours ago. He’d sat through the actual news at one o’clock because the remote control was at the other side of the room and moving was beyond his mental effort.”

7: Pea’s Book of Best Friends, Susie Day (2012)

“It was a disappointment, finding out that adulthood didn’t fix that sort of worry all by itself. But then Mum and Dr Paget started talking about films they’d wanted to see but forgotten to, and books everyone else seemed to have read, and the terrifyingly addictive lure of Homes under the Hammer, and Pea knew it would be all right.”

6: The One Memory of Flora Banks, Emily Barr (2017)

“There is a TV on. A man and a woman are on the screen, talking directly to me, saying, “The kitchen renovation.” It suddenly stops and the words Homes Under the Hammer appear on the screen. I don’t know why homes would be under a hammer.”

5: Television Hell by Luke Whiteman – HMP Leicester, Inside Poetry Volume One (2009)

“I’ve never watched so much TV,

Since that judge imprisoned me.

They put me in a prison cell,

With a man from TV hell.

A true original soap queen,

With eyes alive like a TV screen.

9.15 in the morning on BBC 1

He starts with Don’t get Done, get Dom

Next is Homes under the Hammer

This guy’s a human TV planner.”4: The Mirror World of Melody Black, Gavin Extence (2015)

“Except I found Homes Under the Hammer anything but innocuous, and I was willing to bet I was not the only one. Homes Under the Hammer was a programme in which smug, middle-aged idiots bought and sold property, usually generating a huge profit while simultaneously pricing the rest of the population out of the market. These people all owned homes already. Many of them owned multiple homes, which was why they were able to borrow such vast sums of money from the bank.”

3: Reality Television and Class, Heather Nunn (2011)

“In Homes under the Hammer (BBC1, 2003-), the hard-headed business side of buying for investment was emphasised as viewers were invited into frequently shabby, half-renovated or derelict properties that have been put under auction. Here, the underside of the property market was present as cameras entered repossessed homes. But the emphasis on property as financial investment prevailed as the viewer watched punters bidding at the auction house and their subsequent transformation of a cheaply purchased property into a viable rentable or resale property.”

2: Staying Alive: How to Get the Best from the NHS, Dr Phil Hammond (2014)

“‘Homes Under the Hammer’ will ruin your day because it will ruin the day of the people in your care. Unless someone has specifically requested to watch daytime TV, do everything you can to prevent them from languishing in front of that loathsome dross.”

1: Doctor Who: In The Blood, Jenny T Colgan (2017)

“Many people looked unhappy, but then, they were watching Homes Under the Hammer.”

Well, you think of a way to write about Homes Under the Hammer. At least I avoided the one I could’ve used by Jeremy Clarkson. You’re welcome. Back next time with a much more exciting programme!

-

“Perhaps I Ought To Chalk It?”: The 9th Most-Broadcast BBC Programme Of All Time

What’s got eight legs, 22 balls and would kill you if it fell on you from a tree?

9: Snooker

(Shown 4882 times, 1937-2021)

All together now: “For those watching in black and white, the pink’s behind the blue…”. Except, Whisperin’ Ted’s infamous line actually came from Pot Black, which is a distinctly different proposition to the next ‘programme’ on the list.

So: Snooker. Always a contender for the top ten, and perhaps a little surprising to see it as low as ninth.

With the sport lacking a unifying ‘Match of the Day‘-style branding, actual tournament play went out under the title of, well, ‘Snooker’ (or variants thereof), taking it into this top ten position. And that’s because, well, there’s been rather a lot of it on the BBC over the years. More of it than you could shake Len Ganley at. And it goes back a lot further than one might expect.

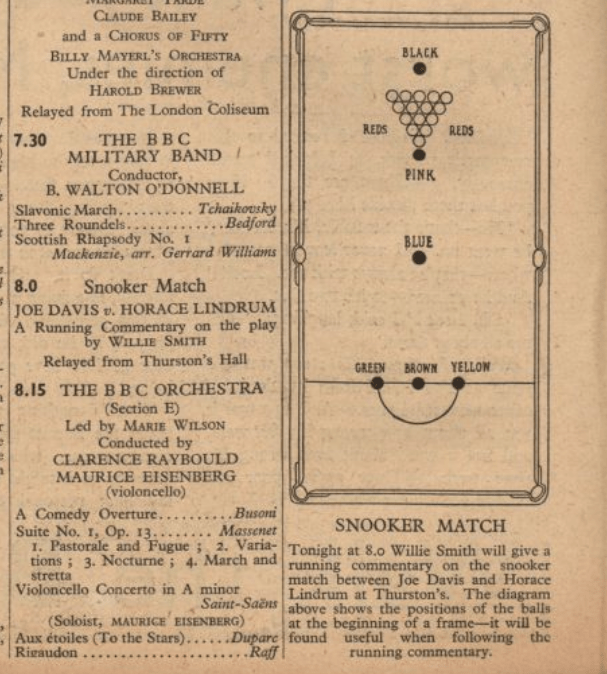

For a spectator sport where identifying colours such as yellow, green, brown, blue, pink and black is pretty darned integral, you’d reasonably expect it to only become a broadcasting event following the advent of colour television. Except, not only was it first broadcast long before BBC2 started pumping out colour programming, snooker was first beamed to the nation before television was a going concern. On Tuesday 10 December 1935, listeners to the London Regional Service were treated to fifteen minutes of commentary on a match-up between England’s Joe Davis, considered the world’s top player at the time, and Australian Horace Lindrum, then considered the globe’s secondmost snookersmith. As if to underline the challenge of describing the action to an audience who’d largely never seen a snooker table in their lives, the Radio Times printed one alongside that day’s radio listings.

For those reading in black and white, etc etc. This would at least have saved Willie Smith spending fourteen minutes trying to explain the setup. How practical that miserly fifteen minutes may have proved is up for debate, of course. Snooker finals are hardly short affairs in this day and age – for example, the 2023 World Championship final between Luca Brecel and Mark Selby was a best of 35 frames. And that’s a brief clatter around a youth club table compared to this match, a prize match to settle a £100-per-man wager, based on two lots of 61 frames. The following day’s Daily Mirror reported that that day’s session had seen Lindrum come back from 10-5 down at the start of the afternoon’s play to draw level on ten frames all, with an aggregate points total of Davis’ 5,223 versus Lindrum’s 5,244.

The report also included mention of the match’s status as broadcasting first, relating how commentator Willie Smith (himself a billiards champion who’d turned his hand to the increasingly lucrative snooker) told of missed sitters (causing “expressions of amazement from spectators”) during that inaugural summary. That match between the two would go on for several more days – at one point breaking so that cheques for £650 could be awarded to Chelsea footballers George Mills and Harold Miller before play continued – only to end with Joe Davis winning by 32 frames to 29, ending the series at one match apiece, and subsequently nullifying the bet. In short: a lot of snooker, then nobody won.

I mean, I say “nobody won”. Of course, that fifteen-minute fix of audio green baize action would be all that radio listeners received from that particular match, but Willie Smith was back on the lip-mic the following February for the rematch. This time, a generous 25 minutes were given to the coverage, which was won (along with the £200 kitty) by Davis. Moreover, snooker had begun to thrill the nation. And put paid to any claim from DLT that he invented Snooker On The Radio.

11 April 1936 saw live coverage from Dublin of a match between Seamus Fleming and W Lowe, as snooker began to grow in popularity in the Irish Free State, while the end of that month saw running commentary from the final of that year’s British Championship, where… Joe Davis beat Horace Lindrum. Again. Another sporting first occurred during sports roundup Saturday Contrast in December, with live coverage of Women’s World Snooker Champion Ruth Harrison as she took on Women’s World Billiards Champion Joyce Gardener, albeit in the discipline of billiards, with a ‘substantial prize’ on offer to the victor.

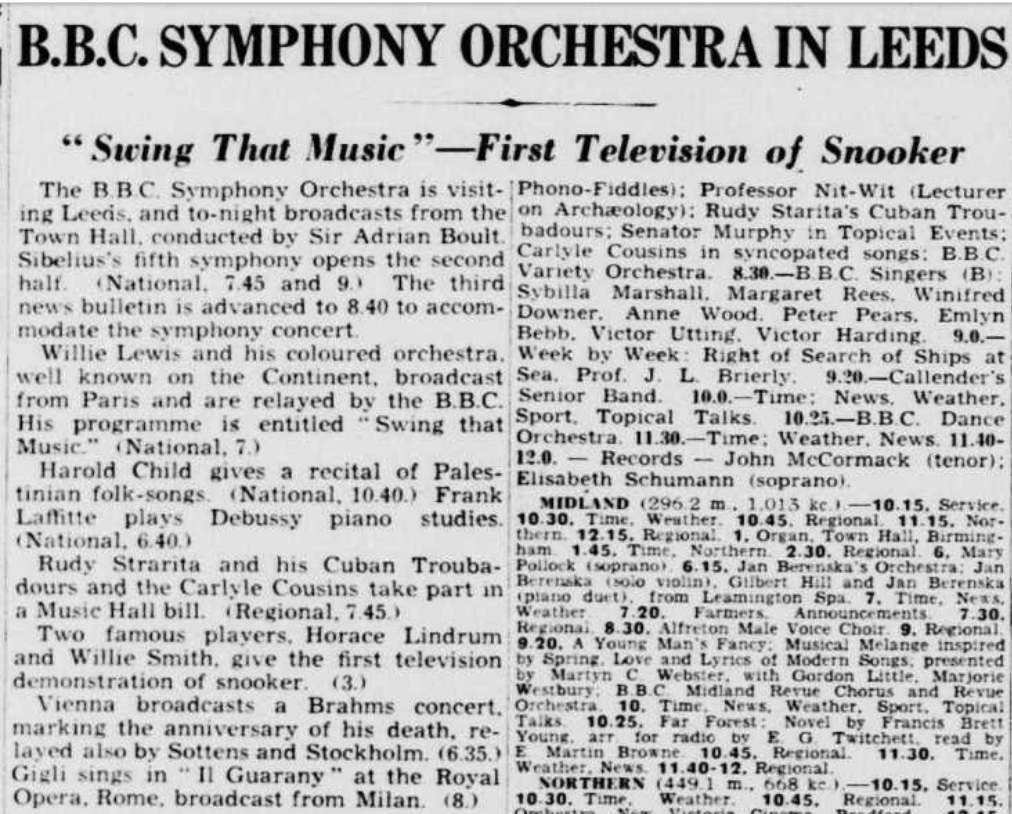

By now, television was on the scene, and surely snooker was a prime sporting candidate for the new medium. Admittedly, visual coverage of the sport would lack the verbal colour of radio commentary, but it would be so much easier to see what was going on, and unlike with many sports, a single fixed camera could be employed to relay the action. And so, on 14 April 1937, snooker was introduced to the television audience for the first time, with an offering billed as An Exhibition of Play by Horace Lindrum and Willie Smith.

Even more excitingly for readers of the Daily Telegraph on the morning of broadcast, there was the implication the event would include full orchestral accompaniment:

Sadly, they were two unrelated broadcasts. Luckily that week’s Radio Times went into more detail. The article explained how, from the early 1930s, snooker had gone from a distraction adopted by billiards professionals once they’d got a bit bored with their day job, to a sport that had overtaken its sister game in popularity. Initially, the announcement that a session of billiards was to be followed by some frames of snooker would result in half the audience suddenly realising they’d left the gas on and would leave the exhibition hall.

But, slowly but surely, billiards’ multiball cousin attracted more of an audience. 1933 saw the first national competition, a handicapped event open to amateur players around the UK. Much to the surprise of the organisers, around five thousand applications poured through the letterbox. Probably going to need a bigger hall, then. And yet, professional cuesmiths preferred to stick to billiards, only occasionally racking up the reds, meaning the growth in participants failed to result in much mainstream attention. Until the arrival on these shores of charismatic Canadian Conrad Stanbury.

While not quite as adept at the sport as homegrown players like Joe Davis, Stanbury added a sense of style, humour and colour to the sport, a stark contrast to the relatively austere Brits. Fellow Canadian Clare O’Donnell also arrived in the UK, taking on well-known billiard pros at snooker, his quick-fire approach to play attracting even more interest in the sport. While the style of the North American duo attracted attention, it was the arrival of Australia’s Horace Lindrum that provided a true rival to top British player Joe Davis. The matches between the two being broadcast over the radio proved how the sport was becoming more popular, and by 1937 former billiards pros were spending more time playing snooker than its parent sport.

In a passage that would prove to age particularly badly, the RT article on the Lindrum-Smith match suggests that it may well be that “the present popularity for snooker will turn out to be just a passing fancy, that the players will tire of constant potting, and welcome a return to cannons and long losers”. How wrong they would turn out to be. After all, snooker would go on to be the biggest game on green baize.

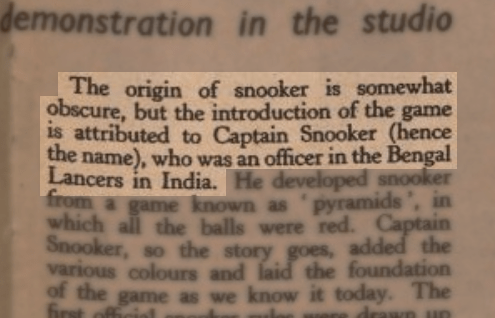

Plus, it certainly didn’t hurt that its origin story can be explained in one of the finest sentences ever published:

Now you’re glad you clicked on this post. Sadly, the above isn’t true, and the common understanding is now that it originated from the brain of Neville “Not That One” Chamberlain in 1875. But still, CAPTAIN SNOOKER. Though all that would come later. For now, it was deemed a sport not yet ready for the viewing public, small monochrome 405-line sets of the era perhaps not providing the optimal viewing experience. As such, following that initial pair of TV broadcasts for snooker on 14 and 16 April 1937, the sport wouldn’t return to BBC-tv (at least under a standalone billing) until 1950.

The dawn of the atomic age didn’t do too much to make snooker a fixture on British TV, however. The decade only saw a smattering of matches broadcast, including “Walter Donaldson (Present World Champion) v. Joe Davis (Retired Undefeated World Champion)” in September 1950. Throughout the decade, the not-as-retired-as-you-may-have-thought Davis featured more than any other player, such was the box office (well, TV licence fee) appeal of the sport’s most decorated player. Even where he wasn’t a competitor in the televised game, such as 1952’s John Barrie-Rex Williams match, he would turn up to perform a few trick shots between frames, such was his appeal.

Come January 1955, a special session of snooker was broadcast to mark the final event at snooker’s then spiritual home, London’s Leicester Square Hall, the centrepiece of the event being an exhibition match between Joe Davis and his brother Fred – himself no slouch on the baize, going on to win eight World Championships between 1948 and 1958.

As the decade progressed, most snooker coverage was folded into the weekly Sportsview round-up, which featured a “Sportsview Potting Competition” that allowed keen cuesmiths to challenge a top professional. And not just in any standard game of snooker, but a specific layout that proved a little more exciting (and more suitable for a segment of a programme just thirty minutes long). Another strand that proved popular was a feature where Joe Davis – playing solo – would attempt to score as high a break as possible within two minutes. The sporting spectacle was slightly undone in one edition where the referee, displaying his keenness to replace a coloured ball as swiftly as possible, accidentally scattered the remaining in-play balls as he did so.

The only standalone coverage of this era came from The News of the World Tournament, which pitted the best players against each other in a round-robin “American-style” format that was considered by many to be of greater importance than the ‘real’ World Championships – not least as the latter no longer featured people’s favourite Joe Davis.

By 1958, Saturday sporting action was safely enclosed in a great big Grandstand umbrella, with initial episodes making great play of challenge matches featuring, inevitably, Joe Davis. And Grandstand provided a safe haven for snooker for much of the next decade, the sport providing a perfect alternative to throw to whenever an outdoor event found itself hamstrung by unpredictable British weather. However, acting as the sporting equivalent of a supply teacher was no life for a proud sport, and once the Beeb’s favourite player finally retired from the sport in 1964 (Joe Davis, as you’ll have guessed), it seems the BBC had lost interest in the sport. Basing much of your coverage around a single superstar in the twilight of his career hadn’t been much of a long-term plan, as it turned out. When Grandstand producer (and snooker fan) Lawrie Davies left the corporation for a role at Yorkshire in 1965, snooker coverage would also depart the BBC.

Fred Davis vs Warren Simpson, 1960. See how disconcertingly close the crowd are. Anyone else feel a bit claustrophobic looking at this video? On the other side, ITV had been having a lot of success with tournaments largely based around the amateur snooker scene. In 1961, this had involved putting together a tournament that saw four top amateur players face off against a quartet of players from the then-tiny pool of professional players. The matches were in a much friendlier TV format – just five frames per match, broadcast live and being much more competitive than the BBC’s exhibition-match coverage – but given the nature of the game, an keener desire to win often led to cautious matches concluding off-screen, as ITV’s attention had long drifted to the classified football results.

Still, what was there was more compelling than Grandstand’s coverage of the Joe Davis Globetrotters, especially in 1962 when amateur player Mark Wildman made the first ever televised century break on ITV, but with monochrome sets still in use, even that wasn’t enough to keep viewers queueing up (ignoring the easy snooker pun, there) for live coverage – especially when there’s no guarantee they’d get to see the final black of the final frame being slammed home. Conversely, matches being settled within just three of the five frames meant coverage finished much earlier than schedules anticipated, leaving a production team frantically trying to fill an additional hour and hardly resulted in tense, captivating snooker.

This lack of popularity caused concerns for the Billiards Association & Control Council. If only more matches lasted the full five frames, and also happened to be wrapped up in a way that meant everything was done and dusted before the vidiprinter clicked into life with the football scores.

Then… that started to happen. A lot more often. Wahey! Exciting snooker! This is what the public wants! Great job everybod… hang on, the Sunday Times have rumbled what’s been going on.

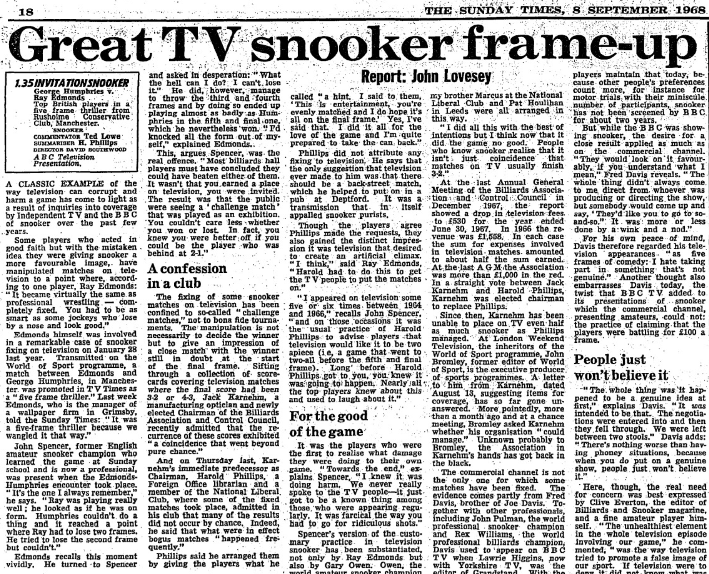

The Sunday Times, 8 Sept 1968 The real giveaway came on 28 January 1967. A invitation match on World of Sport between George Humphries and Ray Edmonds was billed as “a five frame thriller”. In the Sunday Times expose the following year, Edmonds came clean: “It was a five-frame thriller because we wangled it that way.”

It hadn’t been easy. At least according to Edmonds, Humphries had been so off his game, Edmonds accidentally won the second frame of the match, and had to put in some concerted cackhandedness to lose the third and fourth frames. By the time the fifth – and only deliberately competitive – frame came around, both players were so full of yips both players struggled to regain any sense of form. And the viewing audience likely reasoned they’d see a more skilled session of snooker down at the local hall at chucking out time.

This was far from a one-off. In the Sunday Times piece, former chair of the Billiards Association and Control Council Harold Phillips admitted that players of televised exhibition matches were given a reminder that “This is entertainment, you’re evenly matched and I do hope it’s all on the final frame”. Perhaps he followed that up by saying “wink wink”, the report doesn’t make it fully clear.

The issue hadn’t been restricted to matches on ITV. Former world champ Fred Davis stating that the BBC would “look on [close matches] favourably, if you understand what I mean”. As a result, Davis began to treat his exhibition matches on the Beeb as “five frames of comedy”, adding that he hated “taking part in something that’s not genuine”. And so, with the scandal scaring ITV away from the sport and the BBC long having given up on it, snooker would be absent from TV screens entirely.

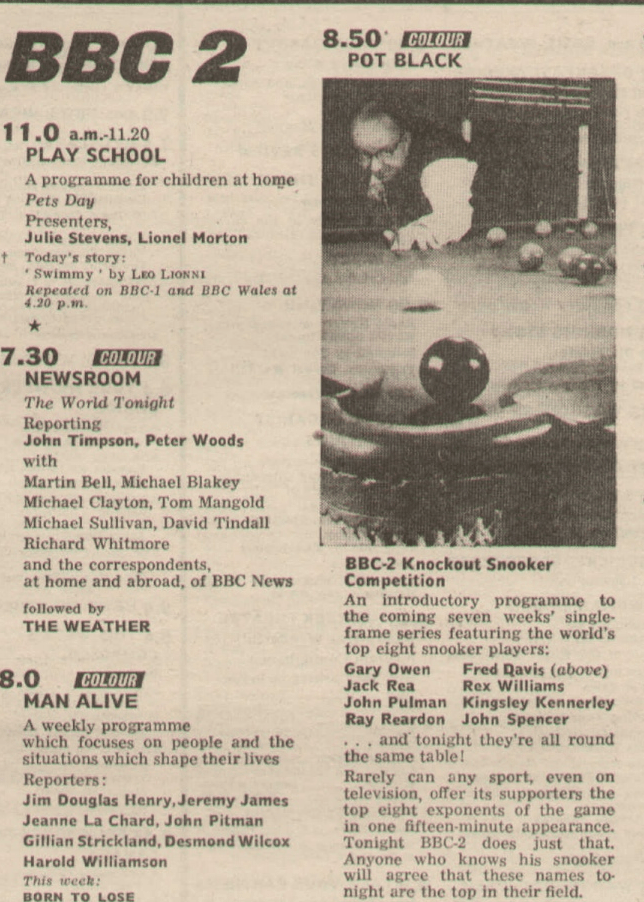

That was, until the advent of colour television on BBC2 and the introduction of a brand new, and very different knockout tournament. One that wouldn’t need thrown frames to manufacture excitement.

“Rarely can any sport, even on television, offer its supporters the top eight exponents of the game in one fifteen-minute appearance. Tonight BBC-2 does just that” boasted the Radio Times listing, and that’s exactly what was on offer here.

Each Wednesday evening, sandwiched between a weighty fifty-minute documentary and an episode of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, a single frame would be played between two of eight top players in a (largely) knockout competition, with one player winning the Pot Black trophy at the end of each series. For those new to the sport, the professionals would be on hand to offer advice (“instead of a pointer, these teachers use a billiard cue”), though given the modest fifteen-minute slot afforded early episodes, any lessons would need to be swiftly delivered.

Despite the popularity of Pot Black, coverage of regular snooker matchplay was still restricted to the BBC’s generic sporting strands. That was to change in the late 1970s, with BBC producer Nick Hunter keen to capitalise on the popularity of the quickfire series. If pre-recorded single frames could attract a BBC-2 audience of four million, Hunter felt that full coverage of snooker tournaments – freed from the shackles of brief Sportsnight highlights – could prove a hit. Players like Ray Reardon and Alex Higgins were helping to forge a new image for the sport within Pot Black, maybe viewers would like to see more of them?