-

So, Has the BBC Run Out of Ideas?

Because it does kind of seem that way, doesn’t it? The schedules dominated by the same old programmes that seem to have been kicking around forever. But – is that really the case? Or, with the main BBC channels being the home for as wide an audience as possible, isn’t it just that the BBC’s programme roster has only ever been refreshed at a leisurely pace?

Well, given I’ve got a ton of programme info to play with (now including all of 2022 and 2023), we can try to look a little deeper into that theory.

If you remember back as far as yesterday, I published decade-by-decade breakdowns of programmes broadcast most frequently by the BBC. That revealed a little about the changes – or lack thereof – in programming policies over BBC Television’s history. Here, we’ll break things down into a slightly smaller chunks and see how much carry-over there is between each five-year period.

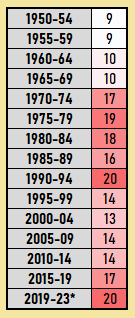

We’ll use the BBC’s TV programming between 1936-39 and 1946-49 as the foundation of this, then look at five-year chunks from 1950 onwards, looking at the 30 most-broadcast programmes from each period. If a programme was also in the Top 30 for the previous period, it gets highlighted and added to a total. The higher the total for that period, the lower the amount of programme turnover for that particular spell. The lower the total, the most inventive the Beeb were (likely) being during that spell, giving increased schedule space to new programmes.

Okay, here we go. Ready for some info tables?

NOTE: To make things fair for the most recent time period, instead of just calculating “2020-2023” (meaning the churn level would likely be lower, as you’re only looking at a four-year rather than five-year spell), I’ve calculated numbers for 2019-2023, and compared it to a comparable list running from 2014-2018. Oh, and this only accounts for programmes broadcast on the (as was) BBC Television Service, and BBC1 and BBC2 from 1964 onwards.

That was a long list, wasn’t it? Here’s the key info, shorn of programme detail:

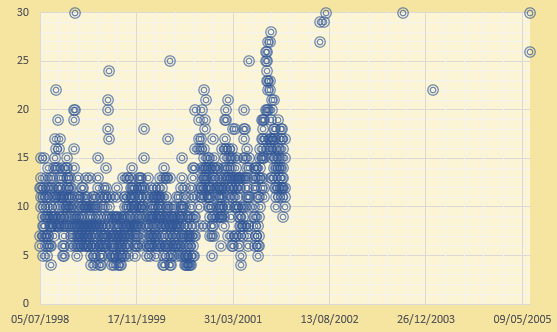

As we can see from the above, the lack of imagination in the BBC schedules really got going from 1970 onwards, and reached a high point (or low point, if you prefer) in the first half of the 1990s. Things got better around the turn of the millennium, but a lack of imagination and risk-taking started to spread as the present day approached. And so, we’re at a point where two-thirds of the BBC’s most-shown programmes were also amongst the most-shown shows from five years earlier.

And so, in conclusion, if we’re pondering the question ‘Has the BBC Run Out of Ideas?’, going by the evidence above, the answer is pretty much “Yeah, but it’s not the first time.” Though, of course, this is pretty telling…

In our next module, T888, we’ll be looking at Social Behaviour of Animals and the History of Wood.

-

The Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes of All-Time: Post-Match Statstravaganza

Okay, now the Big Final Reveal is out of the way, and we’ve identified the two programmes broadcast more than any other on the main BBC channels, let’s get granular. After all, with so much lovely data to build statistical sandcastles with, we can pull that programme information into some other shapes too.

For example, it’s one thing giving all that weight to programmes broadcast as daytime filler, but what about restricting the list to broadcasts going out to audiences sitting down for a proper evening’s televiewing? Or lists of most-shown shows from each decade, helping identify the changing face of BBC Television since 1936? Or just stuff shown on Sundays? And other things, too.

Well, strap in, because here come some ordered lists, without any of that fusty old detail getting in the way. Starting off with a list of:

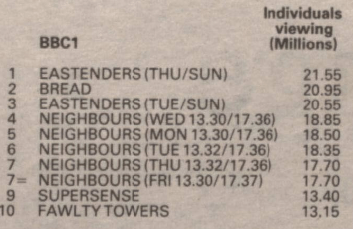

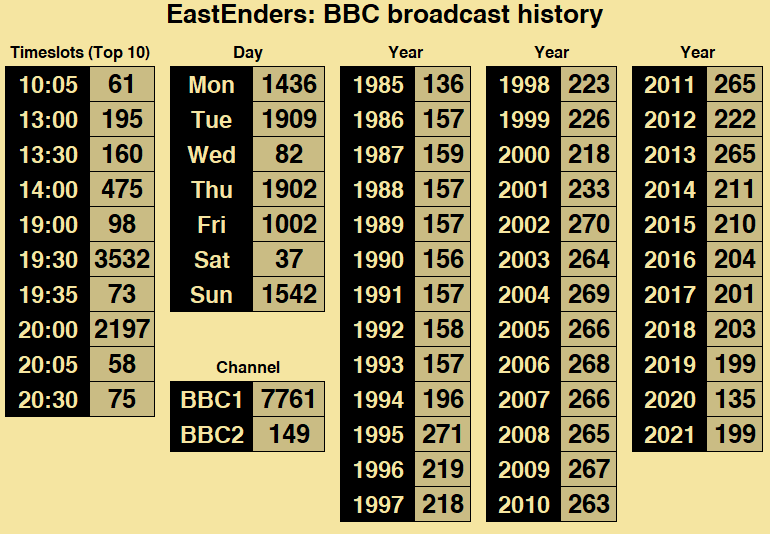

PRIMETIME BROADCASTS ONLY

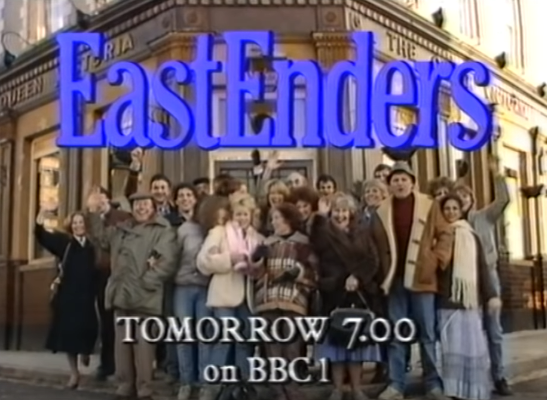

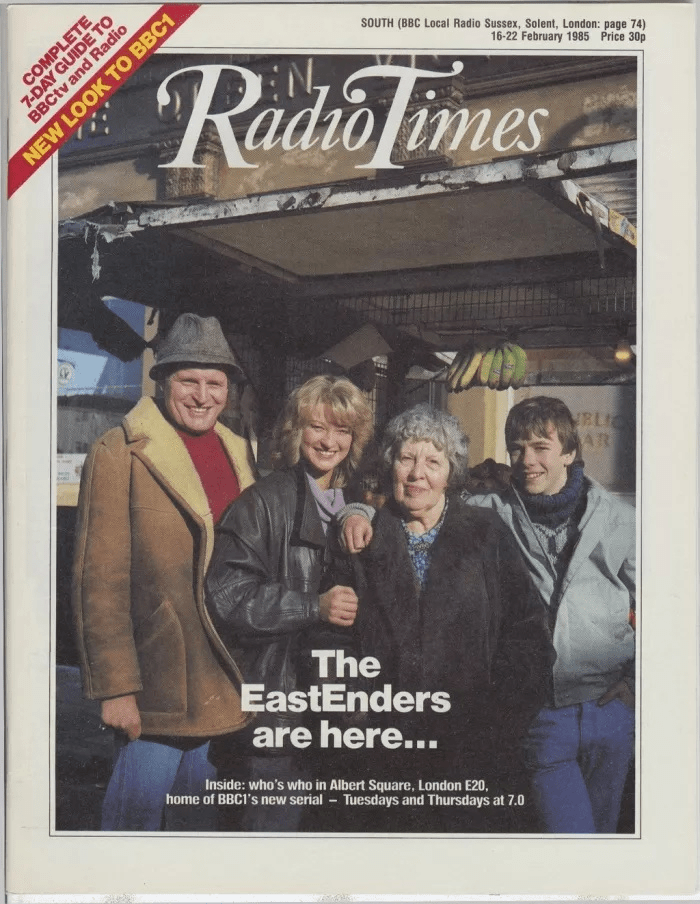

Now, it’s arguable what constitutes ‘primetime’, but the most common categorisation I’ve seen suggests 7pm to 11pm. So, that’s what I’ve calculated and come up with the following list. And, despite being shorn of those Sunday omnibuses, the regulars at the Queen Vic still have enough in the tank to roar past all the other contenders.

- EastEnders

Broadcast 6116 times

BBC1 1985-2021, BBC2 2011-2021 - The One Show

3333 times

BBC1 2007-2021, BBC2 2011-2021 - Match of the Day

2563 times

BBC1 1966-2021, BBC2 1964-2020 - Panorama

2124 times

BBC-tv 1953-1964, BBC1 1964-2021, BBC2 2012 - Top of the Pops

2097 times

BBC1 1964-2012, BBC2 1996-2021 - Gardeners’ World

1521 times

BBC2 1968-2021 - Question Time

1383 times

BBC1 1979-2021 - A Question of Sport

1380 times

BBC1 1975-2021, BBC2 2011-2013 - Twenty-Four Hours / 24 Hours

1360 times

BBC1 1965-1972 - Wogan

1107 times

BBC1 1982-1993 - University Challenge

1096 times

BBC2 1994-2021 - Holby City

1075 times

BBC1 1999-2021, BBC2 2012-2021 - Top Gear

1074 times

BBC1 2020-2021, BBC2 1978-2020 - Points of View

1035 times

BBC-tv 1962-1964, BBC1 1964-1999 - Tomorrow’s World

975 times

BBC1 1965-2003 - Casualty

935 times

BBC1 1986-2021 - Watchdog

881 times

BBC1 1988-2019 - Mastermind

881 times

BBC1 1972-1997, BBC2 2003-2021 - The Money Programme

833 times

BBC1 1974-1974, BBC2 1966-2009 - Party Political Broadcast (etc)

832 times

BBC-tv 1950-1963, BBC1 1969-2021, BBC2 1969-2009 - QI

755 times

BBC1 2009-2011, BBC2 2003-2021 - Snooker

728 times

BBC-tv 1950-1955, BBC1 1978-1997, BBC2 1978-2020 - Omnibus

720 times

BBC1 1967-2001, BBC2 1967-2006 - Have I Got News for You

700 times

BBC1 2007-2021, BBC2 1990-2021 - Late Night Line-Up

694 times

BBC2 1964-1972 - The World About Us

677 times

BBC2 1967-1986 - Z Cars

674 times

BBC-tv 1962-1964, BBC1 1964-1978, BBC2 1993-1993 - Dad’s Army

670 times

BBC1 1968-2020, BBC2 1983-2021 - Tonight

653 times

BBC-tv 1957-1964, BBC1 1964-1979 - Sportsnight

533 times

BBC1 1968-1997, BBC2 1995-1995

Onto lists of most broadcast things by decade…

1930s/40s

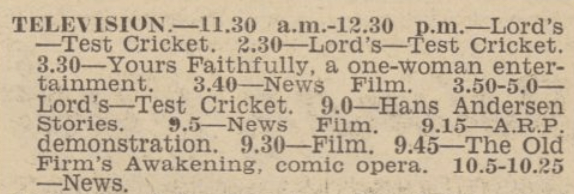

Starting off with a pseudo-decade collected together due to There Being No Telly Before 1936 and That Bloody War Ruining Things For Everybody. Which, as you’ll see, doesn’t make an especially illuminating list, due to most programme titles at the time being descriptive rather than snappy (“First Aid in the Home” or “In Your Garden: The Construction of a Small Lily Pond“), meaning there are some very low episode counts (often operating under vague titles like ‘Variety‘) making the cut here.

[EDIT: Figures for Picture Page corrected, with thanks to Daniel James Webb for pointing out the lower-than-expected total there. And then corrected some of the other numbers, too.]

- Picture Page | 421 times, 1936-1949

- For the Children | 174 times, 1937-1949

- Starlight | 166 times, 1936-1949

- Cricket | 151 times, 1938-1949

- Music Makers | 144 times, 1936-1949

- Variety | 137 times, 1936-1949

- Cabaret | 123 times, 1936-1946

- Boxing | 92 times, 1936-1949

- In Our Garden | 71 times, 1937-1949

- Friends from the Zoo | 56 times, 1936-1947

- Wimbledon | 52 times, 1937-1949

- Stars in Your Eyes | 49 times, 1946-1949

- Racing | 49 times, 1946-1949

- Forecast of Fashion | 46 times, 1938-1947

- Kaleidoscope | 45 times, 1946-1949

- For the Housewife | 44 times, 1948-1949

- Interval, Time, Weather | 44 times, 1936-1936

- Designed for Women | 42 times, 1947-1949

- Cookery | 42 times, 1946-1948

- Pre-View | 33 times, 1937-1938

- Cartoonists’ Corner | 32 times, 1946-1948

- Gardening | 31 times, 1937-1948

- Theatre Parade | 30 times, 1937-1938

- The Zoo | 29 times, 1938-1949

- Fashion Forecast | 27 times, 1937-1946

- Vanity Fair | 27 times, 1939-1939

- Interval | 27 times, 1937-1939

- Composer at the Piano | 26 times, 1946-1947

- Speaking Personally | 25 times, 1937-1947

- Wrestling | 24 times, 1946-1947

1950s

Onto BBC Television’s first full decade, and things are starting to take shape. with some programmes that would go on to become very familiar to viewers for years to come. Also: “Schools Tuning Signal“.

1. Cricket | 859 times, 1950-1959

2. For the Children | 808 times, 1950-1952

3. Mainly for Women | 765 times, 1955-1959

4. Tonight | 624 times, 1957-1959

5. For the Schools | 442 times, 1957-1959

6. Racing | 371 times, 1950-1959

7. Wimbledon | 313 times, 1950-1959

8. For Women | 241 times, 1951-1955

9. What’s My Line? | 227 times, 1951-1959

10. Today’s Sport | 213 times, 1955-1959

11. The Brains Trust | 199 times, 1956-1959

12. Schools Tuning Signal | 193 times, 1957-1959

13. Lunchtime Cricket Scores | 188 times, 1958-1959

14. Gardening Club | 187 times, 1955-1959

15. The Phil Silvers Show | 177 times, 1957-1959

16. The Burns and Allen Show | 175 times, 1955-1959

16. The Epilogue | 175 times, 1952-1959

18. Sportsview | 174 times, 1954-1959

19. Party Political Broadcast (etc) | 173 times, 1950-1959

20. Andy Pandy | 170 times, 1950-1957

21. In Town Tonight | 165 times, 1954-1956

22. Meeting Point | 154 times, 1956-1959

23. Sports Special | 149 times, 1955-1959

24. About the Home | 144 times, 1952-1955

25. Panorama | 142 times, 1953-1959

26. The Grove Family | 141 times, 1954-1957

27. Wells Fargo | 137 times, 1957-1959

28. I Married Joan | 135 times, 1955-1959

29. For the Very Young | 119 times, 1951-1953

30. This Is Your Life | 116 times, 1955-1959

1960s

Onto the decade when London swang like a pendulum, and it’s nice to consider that lots of cool young things were finishing their tea watching Zena Skinner perfecting a bacon, onion and apple roll in that night’s Town and Around before swanning off down the Kings Road.

1. Town and Around | 2044 times, 1960-1969

2. Play School | 1772 times, 1964-1969

3. Late Night Line-Up | 1530 times, 1964-1969

4. Tonight | 1184 times, 1960-1965

5. Cricket | 981 times, 1960-1969

6. Jackanory | 934 times, 1965-1969

7. Twenty-Four Hours / 24 Hours | 786 times, 1965-1969

8. Blue Peter | 696 times, 1960-1969

9. Grandstand | 664 times, 1960-1969

10. Z Cars | 563 times, 1962-1969

11. Meeting Point | 562 times, 1960-1968

12. Farming | 486 times, 1960-1969

13. The Newcomers | 430 times, 1964-1969

14. Panorama | 398 times, 1960-1969

14. Juke Box Jury | 398 times, 1960-1967

16. Compact | 392 times, 1962-1965

17. Songs of Praise | 384 times, 1961-1969

18. The Magic Roundabout | 370 times, 1965-1969

19. Points of View | 358 times, 1961-1969

20. Gardening Club | 338 times, 1960-1967

21. Top of the Pops | 312 times, 1964-1969

22. Spotlight | 307 times, 1960-1965

23. Apna Hi Ghar Samajhiye | 303 times, 1966-1969

24. Seeing and Believing | 297 times, 1960-1969

25. Signpost | 295 times, 1961-1965

26. Junior Points of View | 290 times, 1963-1969

27. Sunday Story | 271 times, 1961-1968

28. Wimbledon | 270 times, 1960-1969

29. Pure Mathematics | 261 times, 1962-1964

30. Doctor Who | 259 times, 1963-1969

1970s

Into the decade where colour TV became a fixture in the brown and beige living rooms of the UK, and it’s good old Humpty & Co that are making the cathode ray tubes their own.

1. Play School | 4998 times, 1970-1979

2. Jackanory | 2140 times, 1970-1979

3. Nationwide | 2037 times, 1970-1979

4. Pebble Mill | 1305 times, 1972-1979

5. Cricket | 1289 times, 1970-1979

6. Nai Zindagi – Naya Jeevan | 857 times, 1970-1979

7. Blue Peter | 843 times, 1970-1979

8. Grandstand | 782 times, 1970-1979

9. Tonight | 771 times, 1975-1979

10. You and Me | 703 times, 1974-1979

11. The Magic Roundabout | 632 times, 1970-1979

12. Twenty-Four Hours / 24 Hours | 605 times, 1970-1972

13. Tom and Jerry | 572 times, 1970-1979

14. Top of the Pops | 524 times, 1970-1979

15. Songs of Praise | 520 times, 1970-1979

16. Farming | 474 times, 1970-1979

17. The Money Programme | 461 times, 1970-1979

18. Late Night Line-Up | 453 times, 1970-1977

19. The World About Us | 452 times, 1970-1979

20. Panorama | 434 times, 1970-1979

21. Tomorrow’s World | 421 times, 1970-1979

22. Match of the Day | 402 times, 1970-1979

23. Golf | 379 times, 1970-1979

24. Open Door | 373 times, 1973-1979

25. The Old Grey Whistle Test | 370 times, 1971-1979

26. On the Move | 355 times, 1975-1978

27. Midweek | 354 times, 1972-1975

28. Wimbledon | 353 times, 1970-1979

29. Z Cars | 343 times, 1970-1978

30. The Wombles | 338 times, 1973-1979

1980s

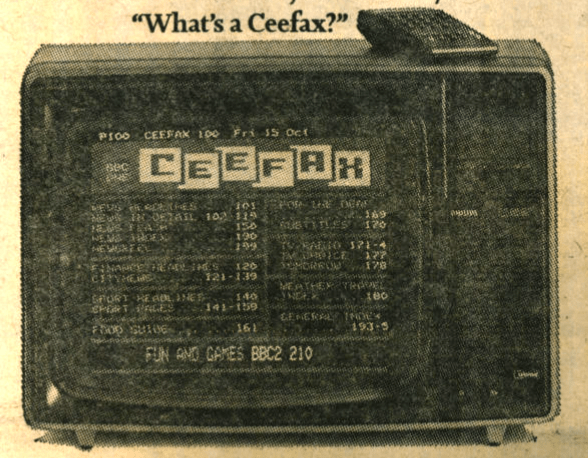

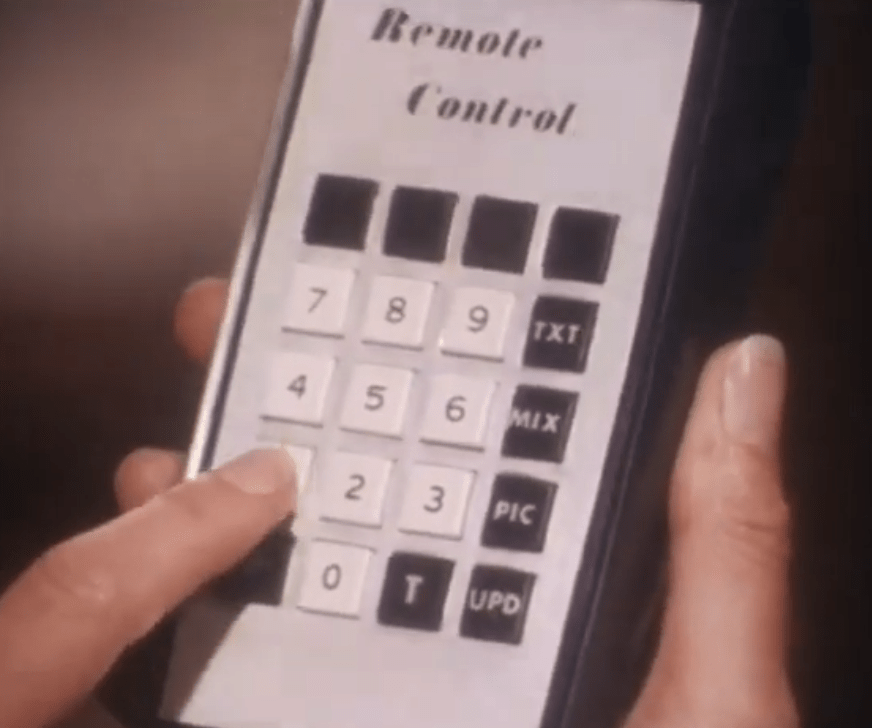

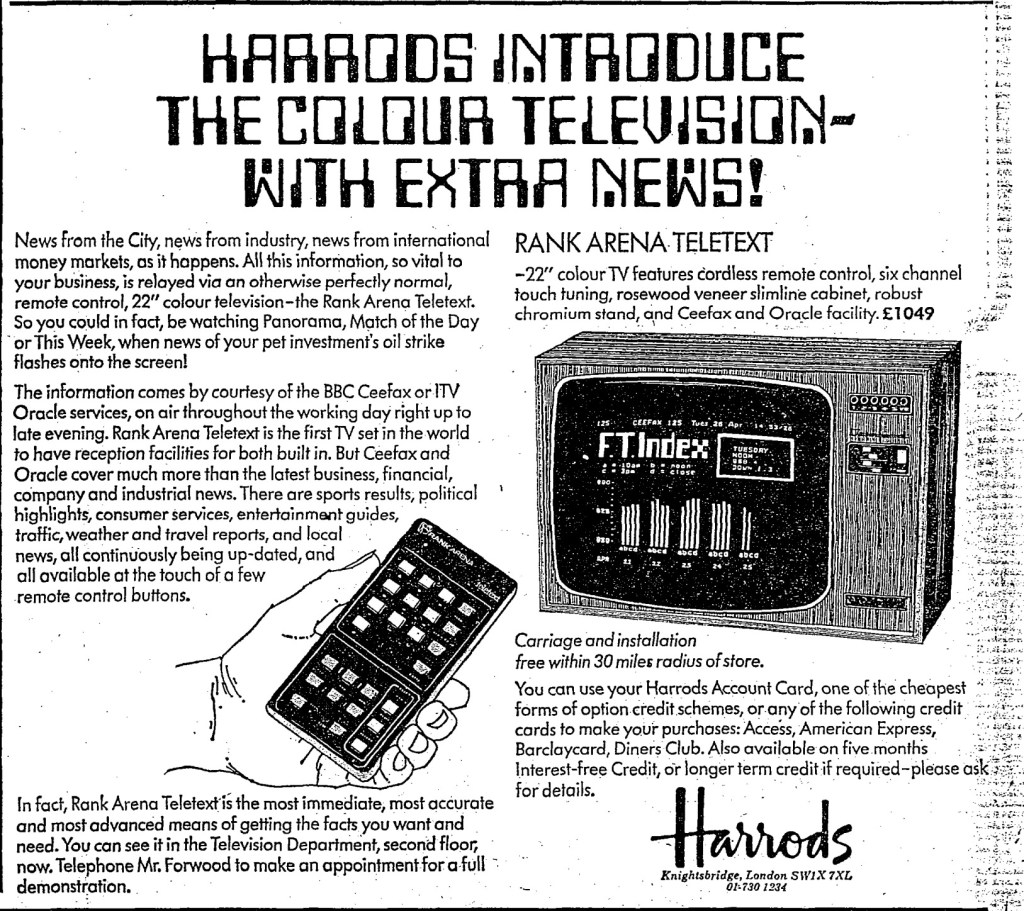

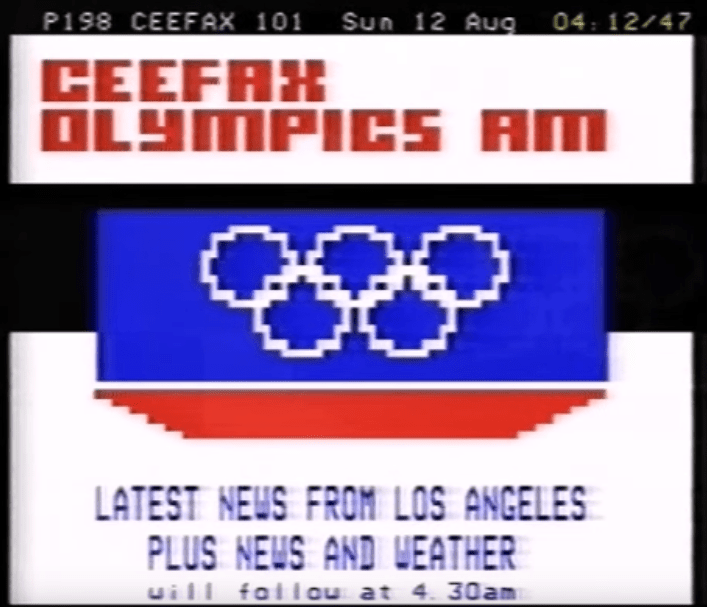

The 1980s saw the home computer revolution fronted by the homegrown likes of Acorn, Amstrad and Sinclair, making it quite fitting that much of the decade saw BBC Micro Mode 7 beamed into the homes of daytime Britain.

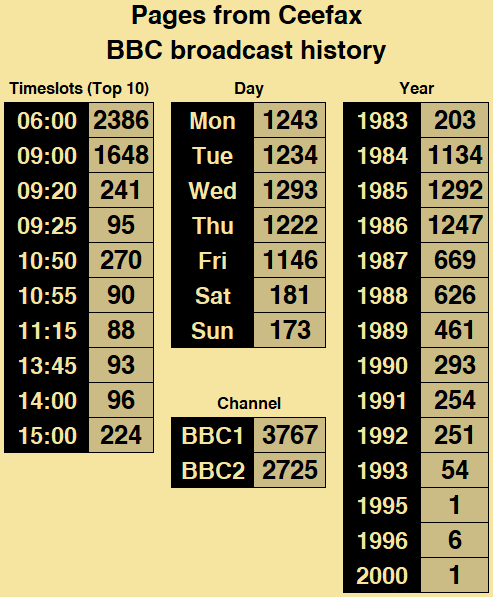

1. Pages from Ceefax | 5634 times, 1983-1989

2. Play School | 3805 times, 1980-1988

3. Breakfast Time | 1727 times, 1983-1989

4. Neighbours | 1633 times, 1986-1989

5. Cricket | 1422 times, 1980-1989

6. You and Me | 1181 times, 1980-1989

7. Snooker | 1176 times, 1980-1989

8. Jackanory | 1123 times, 1980-1989

9. Pebble Mill | 1097 times, 1980-1986

10. Grandstand | 957 times, 1980-1989

11. Blue Peter | 865 times, 1980-1989

12. Nationwide | 845 times, 1980-1983

13. Songs of Praise | 793 times, 1980-1989

14. Wogan | 768 times, 1982-1989

15. EastEnders | 764 times, 1985-1989

16. Five to Eleven | 745 times, 1986-1989

17. Laurel and Hardy | 530 times, 1980-1989

18. Top of the Pops | 526 times, 1980-1989

18. Gardeners’ World | 526 times, 1980-1989

20. Golf | 510 times, 1980-1989

21. Film [xx] (The Film Programme) | 443 times, 1980-1989

22. Farming | 436 times, 1980-1988

23. The Flintstones | 430 times, 1985-1989

24. Points of View | 424 times, 1980-1989

25. Tomorrow’s World | 423 times, 1980-1989

25. Kilroy | 423 times, 1986-1989

27. Playdays | 394 times, 1988-1989

28. See Hear! | 389 times, 1981-1989

28. Grange Hill | 389 times, 1980-1989

30. Dallas | 378 times, 1980-1989

1990s

Here come the nineties, decade of Britpop, Alcopop and antipodean domination of the TV listings, between Home & Away, Prisoner Cell Block H and the show at the top of the pile on BBC1.

1. Neighbours | 5183 times, 1990-1999

2. Playdays | 2989 times, 1990-1999

3. EastEnders | 1981 times, 1990-1999

4. Blue Peter | 1609 times, 1990-1999

5. Kilroy | 1606 times, 1990-1999

6. Westminster | 1236 times, 1990-1999

7. Cricket | 1206 times, 1990-1999

8. Teletubbies | 1180 times, 1997-1999

9. Working Lunch | 1104 times, 1994-1999

10. Grandstand | 1099 times, 1990-1999

11. Snooker | 1048 times, 1990-1999

12. Pages from Ceefax | 859 times, 1990-1996

13. Ready Steady Cook | 774 times, 1994-1999

14. See Hear! | 761 times, 1990-1999

15. Today’s the Day | 741 times, 1993-1999

16. Pebble Mill | 728 times, 1991-1996

17. Can’t Cook Won’t Cook | 689 times, 1995-1999

18. Top of the Pops | 688 times, 1990-1999

19. CountryFile | 681 times, 1990-1999

20. You and Me | 671 times, 1990-1995

21. The Late Show | 643 times, 1990-1995

22. Grange Hill | 638 times, 1990-1999

23. Songs of Praise | 584 times, 1990-1999

23. Good Morning … with Anne and Nick | 584 times, 1992-1996

25. The O Zone | 581 times, 1990-1999

26. BBC Select | 567 times, 1992-1995

27. Match of the Day | 563 times, 1990-1999

28. Film [xx] (The Film Programme) | 560 times, 1990-1999

29. The Weather Show | 550 times, 1996-1999

30. The Learning Zone | 549 times, 1995-1998

2000s

It’s the post-millennial cyberfuture! And the start of Anne Robinson’s rise to global domination.

This is, of course, from Tomorrow’s World reporting on the worldwide web in 1994. But still. 1. Neighbours | 3810 times, 2000-2008

2. EastEnders | 2580 times, 2000-2009

3. Tweenies | 2266 times, 2000-2009

4. The Weakest Link | 2205 times, 2000-2009

5. Working Lunch | 2064 times, 2000-2009

6. Teletubbies | 1797 times, 2000-2009

7. Bargain Hunt | 1761 times, 2000-2009

8. Doctors | 1734 times, 2000-2009

9. Ready Steady Cook | 1631 times, 2000-2009

10. Blue Peter | 1561 times, 2000-2009

11. Arthur | 1453 times, 2000-2009

12. Cash in the Attic | 1375 times, 2002-2009

13. Match of the Day | 1363 times, 2000-2009

14. Flog It! | 1307 times, 2002-2009

15. Snooker | 1305 times, 2000-2009

16. Diagnosis Murder | 1141 times, 2000-2009

17. The Daily Politics | 1134 times, 2003-2009

18. Homes under the Hammer | 1070 times, 2003-2009

19. Kilroy | 977 times, 2000-2004

20. Animal Park | 965 times, 2000-2009

21. To Buy or Not to Buy | 934 times, 2003-2009

22. Murder, She Wrote | 917 times, 2002-2009

23. Scooby-Doo | 908 times, 2002-2009

24. Escape to the Country | 886 times, 2002-2009

25. Grandstand | 879 times, 2000-2007

26. Balamory | 858 times, 2003-2009

27. Fimbles | 839 times, 2002-2009

28. Eggheads | 828 times, 2003-2009

29. Tikkabilla | 765 times, 2003-2009

30. ChuckleVision | 699 times, 2000-2009

2010s

And so, onto the last full decade on the list, and television is drowning in daytime nan-fodder.

1. Homes under the Hammer | 3513 times, 2010-2019

2. Bargain Hunt | 3293 times, 2010-2019

3. Escape to the Country | 2898 times, 2010-2019

4. Flog It! | 2686 times, 2010-2019

5. The ONE Show | 2324 times, 2010-2019

6. EastEnders | 2222 times, 2010-2019

7. Pointless | 2130 times, 2010-2019

8. Doctors | 2078 times, 2010-2019

9. Eggheads | 2022 times, 2010-2019

10. The Daily Politics | 1650 times, 2010-2018

11. Antiques Road Trip | 1229 times, 2010-2019

12. CountryFile | 1195 times, 2010-2019

13. Match of the Day | 1053 times, 2010-2019

14. Holby City | 1043 times, 2010-2019

15. Coast | 1042 times, 2010-2019

16. Cash in the Attic | 856 times, 2010-2017

17. Antiques Roadshow | 847 times, 2010-2019

18. Great British Menu | 832 times, 2010-2019

19. Panorama | 825 times, 2010-2019

20. Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is | 804 times, 2010-2019

21. Rip Off Britain | 738 times, 2010-2019

22. Heir Hunters | 719 times, 2010-2019

23. Question Time | 710 times, 2010-2019

24. The Weakest Link | 706 times, 2010-2013

25. Gardeners’ World | 693 times, 2010-2019

26. Wanted Down Under | 678 times, 2010-2019

27. Great British Railway Journeys | 675 times, 2010-2019

28. The Graham Norton Show | 658 times, 2010-2019

28. A Question of Sport | 658 times, 2010-2019

30. Waybuloo | 641 times, 2010-2012

What about those weekend days, when telly is a very different beast. The full list was, predictably, dominated by weekday programming. So what went out most frequently at the weekend? And, as Saturday Telly is a distinctly different beast to Sunday Telly, here are lists for each:

SATURDAYS

1. Grandstand | 2627 times, 1958-2007

2. Match of the Day | 1847 times, 1964-2021

3. Cricket | 945 times, 1938-2021

4. Saturday Kitchen | 886 times, 2001-2021

5. Casualty | 869 times, 1986-2021

6. Football Focus | 831 times, 1977-2021

7. Final Score | 755 times, 1971-2021

8. Snooker | 734 times, 1952-2021

9. Doctor Who | 728 times, 1963-2017

10. Dad’s Army | 701 times, 1969-2021

11. Flog It! | 534 times, 2002-2021

12. Top of the Pops | 469 times, 1965-2021

13. Golf | 444 times, 1946-2021

14. Weekend 24 | 414 times, 1998-2006

15. Juke Box Jury | 408 times, 1959-1979

16. Dixon of Dock Green | 395 times, 1955-1976

17. Today’s Sport | 388 times, 1956-1980

18. See Hear! | 387 times, 1998-2014

19. The Sky at Night | 386 times, 1957-2013

19. Rugby Special | 386 times, 1966-2005

21. Pointless Celebrities | 375 times, 2012-2021

22. Tennis | 302 times, 1939-2021

23. Scooby-Doo | 301 times, 1976-2012

24. Parkinson | 300 times, 1971-2021

25. Athletics | 296 times, 1947-2021

26. Escape to the Country | 287 times, 2005-2021

27. Bargain Hunt | 279 times, 2008-2021

28. What the Papers Say | 278 times, 1990-2008

29. Arthur | 274 times, 2000-2011

30. TOTP2 | 270 times, 1994-2021

SUNDAYS

Unsurprisingly, Songs of Praise tops the list. But surprisingly, no place in the thirty for That’s Life – while it aired 442 times, 140 of those broadcasts were on other days of the week (mainly Saturdays). That just doesn’t seem right, does it? 1. Songs of Praise | 2790 times, 1961-2021

2. CountryFile | 2083 times, 1988-2021

3. EastEnders | 1538 times, 1985-2017

4. Farming | 1438 times, 1958-1988

5. Match of the Day | 1385 times, 1980-2021

6. Antiques Roadshow | 1059 times, 1979-2021

7. Grandstand | 1011 times, 1966-2007

8. Meeting Point | 716 times, 1956-1968

8. The Money Programme | 716 times, 1973-2007

10. Nai Zindagi – Naya Jeevan | 659 times, 1968-1982

11. The Andrew Marr Show | 644 times, 2007-2021

12. The World About Us | 640 times, 1967-1986

13. Snooker | 607 times, 1957-2021

14. Holby City | 591 times, 2006-2021

15. See Hear! | 576 times, 1981-2000

16. Breakfast with Frost | 575 times, 1993-2005

17. Rugby Special | 549 times, 1975-2005

18. Natural World | 529 times, 1983-2021

19. Cricket | 485 times, 1953-2021

20. Saturday Kitchen Best Bites | 482 times, 2012-2021

21. Escape to the Country | 479 times, 2005-2021

22. Seeing and Believing | 470 times, 1960-1976

23. Bargain Hunt | 459 times, 2005-2021

24. Points of View | 454 times, 1999-2021

25. Everyman | 450 times, 1977-2000

26. Playdays | 449 times, 1988-1997

27. The Sky at Night | 434 times, 1969-2013

28. Lifeline | 416 times, 1986-2021

29. Top Gear | 415 times, 1981-2021

30. This is the Day | 402 times, 1980-1994

POST-WATERSHED BROADCASTS

Next up, how about a list of hot and steamy late-night programming definitely deemed unsuitable for children. Picking out broadcasts purely between 9pm and 5am, here’s a list of most-seen X-rated telly ethemera. Phwoar!

This image might seem to disprove what I’d just said, but don’t forget the time Jimmy Hill accidentally advised viewers to “put their cocks back” 1. Match of the Day | 2713 times, 1965-2021

2. Late Night Line-Up | 1989 times, 1964-1989

3. Question Time | 1834 times, 1979-2021

4. Snooker | 1539 times, 1977-2021

5. Twenty-Four Hours / 24 Hours | 1390 times, 1965-1972

6. Film [xx] (The Film Programme) | 1335 times, 1971-2018

7. Cricket | 1216 times, 1952-2021

8. Party Political Broadcast (etc) | 891 times, 1950-2021

9. Panorama | 869 times, 1954-2021

10. Have I Got News for You | 856 times, 1990-2021

11. The Graham Norton Show | 837 times, 2001-2021

12. The Late Show | 802 times, 1966-1995

13. Later… with Jools Holland | 794 times, 1992-2021

14. Tonight | 772 times, 1975-1992

15. QI | 734 times, 2003-2021

16. Omnibus | 721 times, 1967-2021

17. The Sky at Night | 717 times, 1957-2013

18. Golf | 613 times, 1953-2021

19. This Week | 610 times, 2003-2019

19. Holby City | 610 times, 2006-2021

21. A Question of Sport | 559 times, 1999-2021

22. Despatch Box | 554 times, 1998-2002

23. The Learning Zone | 547 times, 1995-1998

24. Friday Night with Jonathan Ross | 522 times, 2001-2010

25. Sportsnight | 517 times, 1968-1997

26. BBC Select | 511 times, 1992-1995

27. Mock the Week | 501 times, 2005-2021

28. Top of the Pops | 467 times, 1965-2021

29. Everyman | 466 times, 1977-2001

30. Parkinson | 459 times, 1971-2021

Finally, how about a list of:

Children’s BBC Programmes

Specifically programmes meeting the criteria “weekday BBC1, start time 3:50-5:55, programmes for grown-ups not counted”. Yes, I could have spent ages picking out summer holiday morning CBBC strands and the like, but even I’m not that bloody minded.

1. Blue Peter | 4303 times, 1964-2012

2. Jackanory | 4104 times, 1965-2006

3. Play School | 3831 times, 1968-1985

4. The Magic Roundabout | 904 times, 1965-1984

5. Grange Hill | 830 times, 1978-2008

6. Byker Grove | 502 times, 1989-2005

7. Scooby-Doo | 480 times, 1970-2012

8. ChuckleVision | 385 times, 1988-2009

9. Yogi Bear | 374 times, 1971-1997

10. Popeye | 369 times, 1979-1999

11. Animal Magic | 358 times, 1964-2000

12. The Wombles | 323 times, 1973-1985

13. Laurel and Hardy | 321 times, 1966-1990

14. Rugrats | 315 times, 1994-2004

15. Junior Points of View | 287 times, 1964-1970

16. SuperTed | 259 times, 1983-1995

17. Record Breakers | 257 times, 1983-2001

18. Shaun the Sheep | 251 times, 2007-2012

18. Hector’s House | 251 times, 1968-1975

20. SMart | 250 times, 1994-2010

21. Mona the Vampire | 247 times, 2000-2006

22. Screen Test | 230 times, 1970-1984

23. The Story of Tracy Beaker | 224 times, 2002-2010

23. Crackerjack | 224 times, 1964-1984

25. The Really Wild Show | 217 times, 1986-2004

26. Paddington | 214 times, 1976-1991

26. Deputy Dawg | 214 times, 1964-1980

28. The Cramp Twins | 213 times, 2001-2008

29. The Wild Thornberrys | 204 times, 1999-2004

30. Bananaman | 203 times, 1983-1999

There we go! That probably counts as a fitting epilogue to a very long-winded project. Onto the blog’s next ill-considered escapade – coming soon. Well, soon-ish. It’s going to involve getting a lot more data in place first. But, given the above, you could probably have guessed that.

- EastEnders

-

Play School: A Look Through the Redux Window (Take Two*)

(*Fingers crossed, first attempt to publish resulted in a blank post and WordPress deleting the contents of my draft. So, fingers crossed. Apologies to email subscribers who received a mostly-empty email last night.)

Who wants a bunch more information about Play School? You know you do. But first, a brief aside.

Funny thing, research.

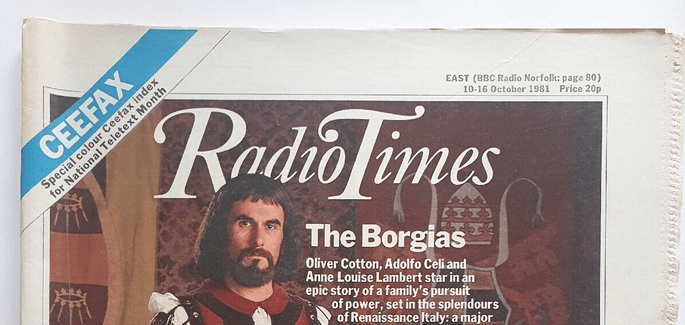

When putting together the write-up on Play School – the most-broadcast BBC programme of all time, of course – I used a variety of sources for background. Old issues of the Radio Times, the British Newspaper Archive’s brilliant archive of The Stage and a number of books came into play, such as Phil Norman’s TV: A History in 100 Programmes, Richard Webber’s That Was the Decade That Was and Ruth Inglis’ The Window in the Corner: A Half Century of Children’s Television. As with a number of entries on the list, Paul R Jackson (no stranger to excellent books about television himself, of course) also provided some brilliant info and clarifications.

And, as with much of the list, contemporary newspaper archives were very handy for finding additional nuggets of information and insight that have rarely resurfaced since original publication. For the most part, that was from a combination of the aforementioned British Newspaper Archive and the Gale Newspaper Archive (which – PROTIP – you can access for free via libraries such as the National Library of Wales). And, in a development which was certainly going to provide some great information, a 1971 Guardian interview with Doreen Stephens, the BBC’s Head of Family Programmes at the time Play School was devised, available on researcher’s pal archive.org.

Using all of this information, I put together the much-abridged history of Play School – as with many programmes on the Top 100 (etc) list, an enjoyable experience on my part, learning a lot I didn’t previously know, and building on lots of information I already-kind-of-sort-of knew from my own childhood. It went online, lots of people read it and hopefully liked it (at least any that didn’t were gratifyingly mute about it). One such person was, as hinted at by the quote at the end of the write-up (and thanks again to Paul R Jackson for sharing the news of it with her) original Play School editor Joy Whitby.

Joy was kind enough to get in touch via email about Play School, and as it turns out, some of the details of that Guardian piece – and my Play School write-up – weren’t quite correct.

For one thing, Play School was entirely Michael Peacock’s idea, rather than just the notion of a pre-school series being his, and passed onto Doreen Stephens to do more work on. In actual fact, Joy was chosen for the Play School role – by a board chaired by Michael Peacock – before Doreen had started her role as Head of Family Programmes. While Doreen was hugely supportive to Joy during her tenure, and remained her friend through to retirement, it was also Michael who went on to commission another daily slot for the Play School team – which ultimately became Jackanory. Joy ran both programmes side by side until, again thanks to Michael’s invitation, she left to join the new London Weekend Television franchise.

That’s not to diminish Doreen Stephen’s hugely impressive time at the BBC, of course. She’d originally turned down various jobs at the BBC before finally agreeing to run Children’s Programmes – but only on the proviso the department’s name be changed to Family Programmes. After her time in that role, the powers that BBC reverted to the old department title: Children’s Programmes.

Joy added that Athene Seyler – Play School’s first ever storyteller, was considered the perfect granny figure, taking the time to reminisce about her childhood. The choice of Zia Mohyeddin as an early Play School storyteller was part of Joy’s decision to give the programme a cosmopolitan feel from the start.

Regarding Doreen Stephens’ tenure heading Family Programmes, when Joy Whitby first met her in her new office, having been told she was a dragon, Stephens welcomed Whitby with something direct and friendly along the lines of: “I didn’t appoint you and you didn’t choose me, but we must get along together…”. Which – as the pair’s long subsequent history of collaboration proved – they evidently did.

Doreen Stephens would later leave her role at LWT in protest at Michael’s dismissal, together with other executives (including Joy Whitby) when he was ousted. This wasn’t due to any particular programme content, it being more likely that commercial pressures being cause of his failure within ITV, especially given the original LWT’s high-falutin’ notions.

As for Joy Whitby’s later series Grasshopper Island, the source of funding was amusingly different. Doreen Stephens initially had nothing to do with the series. Whitby’s secretary at LWT was at a dinner sat next to a young merchant banker, her dining neighbour sharing that there were still people like himself who wanted to finance creative people – in the manner previously seen in the days of Beethoven and Mozart. She told him about the new project, and as a result the banker swiftly got in touch, and raised a consortium who funded Grasshopper Island. Most of the series was shot in Corsica where cast member Frank Muir had a holiday home, Muir being another ex-BBC/LWT executive who had stood by Michael Peacock.

Plus, it’s a boon for people who enjoy seeing Tim Brooke-Taylor playing multiple roles. Which is any right-minded person. Around the same time Brooke-Taylor was doing a similar trick in Orson Welles’ One Man Band, too. Joy Whitby asked Doreen to join the project as general manager, and as a result she ended up not only taking on the task of sorting out contracts and the like, but also in cooking meals for everyone. As Joy points out, “she was a hands-on friend – without any need to pull rank. Much respected and much loved by us all.”

Now, as splendid as screencaps of Tim Brooke-Taylor being frumpy are, how about an extra Play School lists (and if you don’t like lists, what are you doing here?), plus: some camera scripts and a gallery of Play School photos, each courtesy of Paul R Jackson?

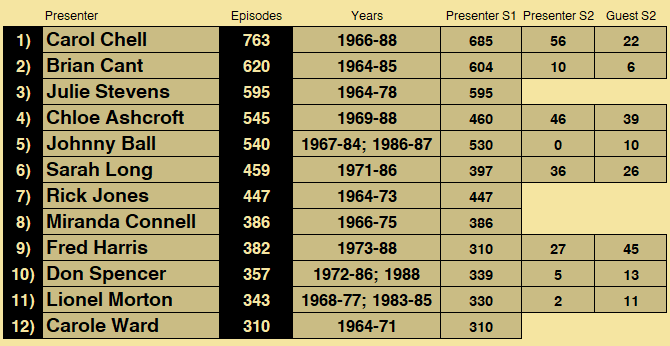

Firstly, here’s a list of PLAY SCHOOL PRESENTERS WITH THE GREATEST NUMBER OF APPEARANCES. Broken down into pre- and post-relaunch totals for good measure:

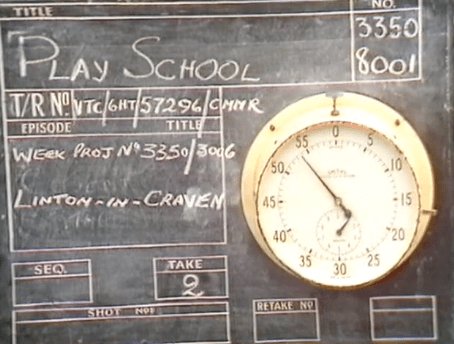

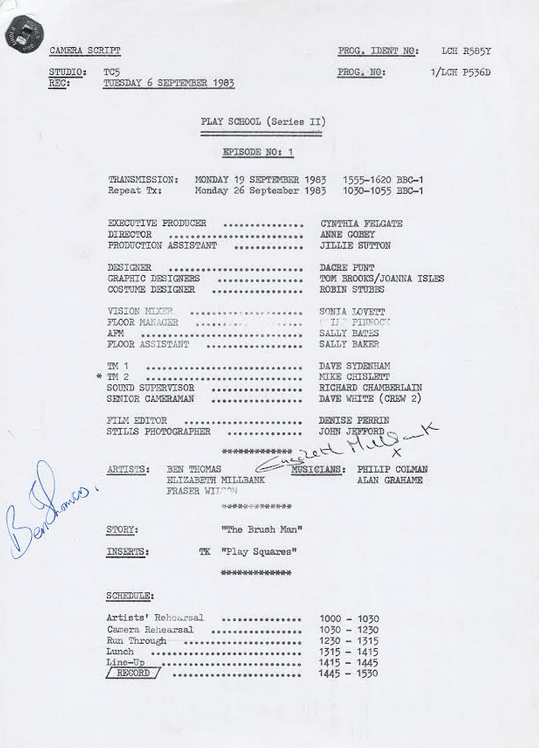

How about some scans? Here’s the front page of the script from Play School’s first episode of Series Two (Recording Tue 6 Sep 1983, TX Mon 19 Sep 1983):

…and the front page of the camera script of the final episode of Series Two (and the series as a whole). Recording Wed 3 Mar 1988, TX Fri 11 Mar 1988

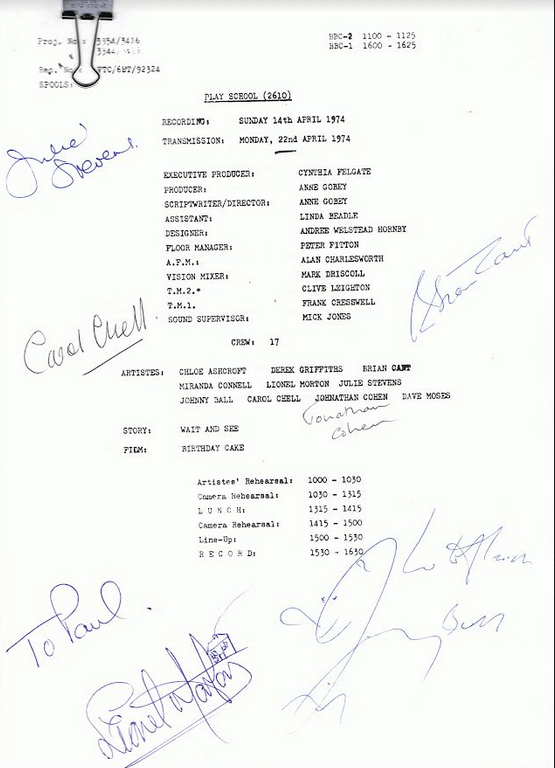

If you prefer Old School Play School, here’s one from the tenth anniversary special (Recording Sun 14 Apr 1974, TX Mon 22 Apr 1974)

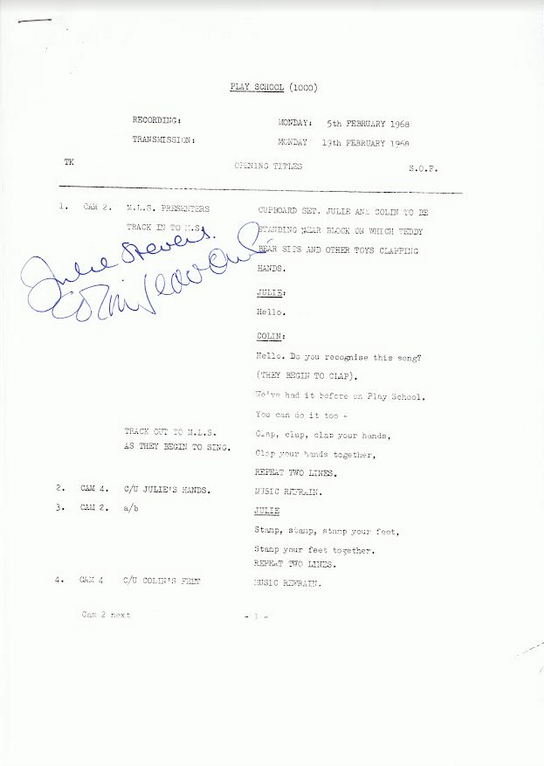

Here’s the front page of the 1000th Play School script (Recording Mon 5 Feb 1968, TX Mon 19 Feb 1968):

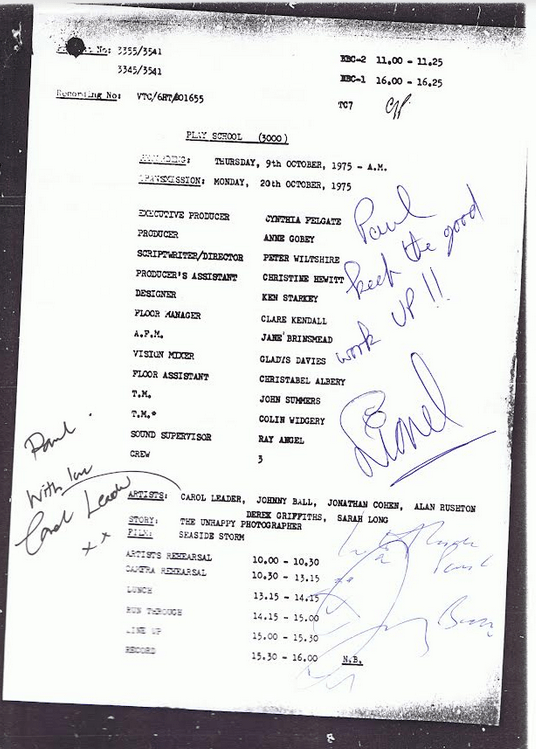

And the 300th episode (Recording Thu 9 Oct 1975, TX Mon 20 Oct 1975):

And – go on, then – the 5000th episode (Recording Mon 25 Jul 1983, TX Mon 12 Sep 1983):

Next the photos! And I can’t think of a better introduction than this group shot from the programme’s 15th anniversary in 1979:

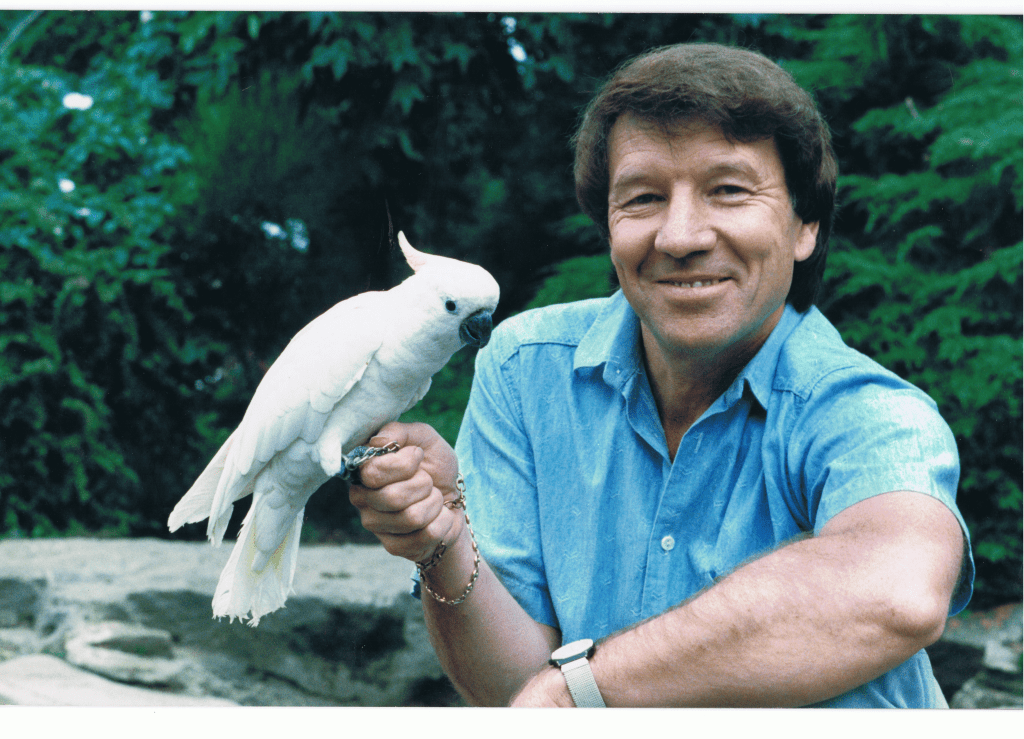

Here’s Australian Play School presenter Don Spencer with the programme’s longest-serving pet, Katoo.

A Lesser Sulphur Crested Cockatoo hailing from Indonesia, or ‘cacatua sulphurea’ if you’re being fancy, Katoo first landed on the Play School set on Wednesday 7 September 1966, aged just one, sticking around until the series ended. Perhaps that lengthy tenure is what led to the feathery diva occasionally refusing to talk on cue, while dancing beautifully with resident pet expert Wendy Duggan… when off camera. Following the end of Play School, Katoo lived with Duggan, surviving until the ripe old age 46 before finally passing away in 2009.

Wendy Duggan and Katoo in 1979.

As mentioned in the piece on Play School, the programme would go on to be a fixture on children’s television around the world. And, befitting the show’s inclusive nature, a number of hosts from the international versions were invited to the BBC for presenting stints on the British original.

Diane Dorgan, Australia’s first female presenter, appeared in her local version of the series between 1966 and 1969, before moving to the UK to present the BBC version between October 1969 and March 1974. The antipodes also provided the series with Don Spencer (Australian version 1968-1992), who presented the BBC version between September 1972 and February 1984, returning as a guest presenter in February 1985 and June 1986, plus in February 1988. An even longer journey was undertaken by New Zealand’s Janine Barry (Jan 1975-Dec 1977), who joined Fred Harris for one edition on 14 August 1981.

A more modest number of air miles were accrued by Play School’s continental contingent, with Miguel Vila (Spain’s La Casa Del Reloj 1971-1973, below) popping over to the UK to join Toni Arthur for a week in August 1973. Further north, Norway’s Lekestue sent Jon Skolmen (1971-1973, also below) for a week presenting the ‘School alongside Carol Chell in November 1971, and producer-writer-presenter Vibeke Saether (1971-1981) appearing alongside Don Spencer on 20 December 1976.

Diane Dorgan, 1966

Miguel Vila

Norway’s Jon Skolmen and Vibeke Saether, 1971 As a bonus, here’s a lovely shot of the New Zealand Play School team, from the Ross Johnston collection:

And how about one of globetrotting Man-About-‘School Don Spencer with Play School Australia’s not-right-at-all-to-British-eyes Humpty from 1983?

As if to prove that Australians are perfectly fine with their wrong-looking Humpty, here he is at the 2016 Logie Awards with several other Play School Australia alumni:

Not that Humpty always gets the limelight, of course. Here’s a photo taken to mark the 45th anniversary of the Australian version, where then-current and former presenters came together to reunite with the team of toys. Perhaps Humpty was feeling a little camera-shy that day.

Finally, to nicely tie everything in with the programme that actually topped the list, here are a pairing of presenters from 1966 – Kerry Francis (top, 20 episodes) and… Ramsay Street’s very own Anne Haddy (bottom left, 44 episodes).

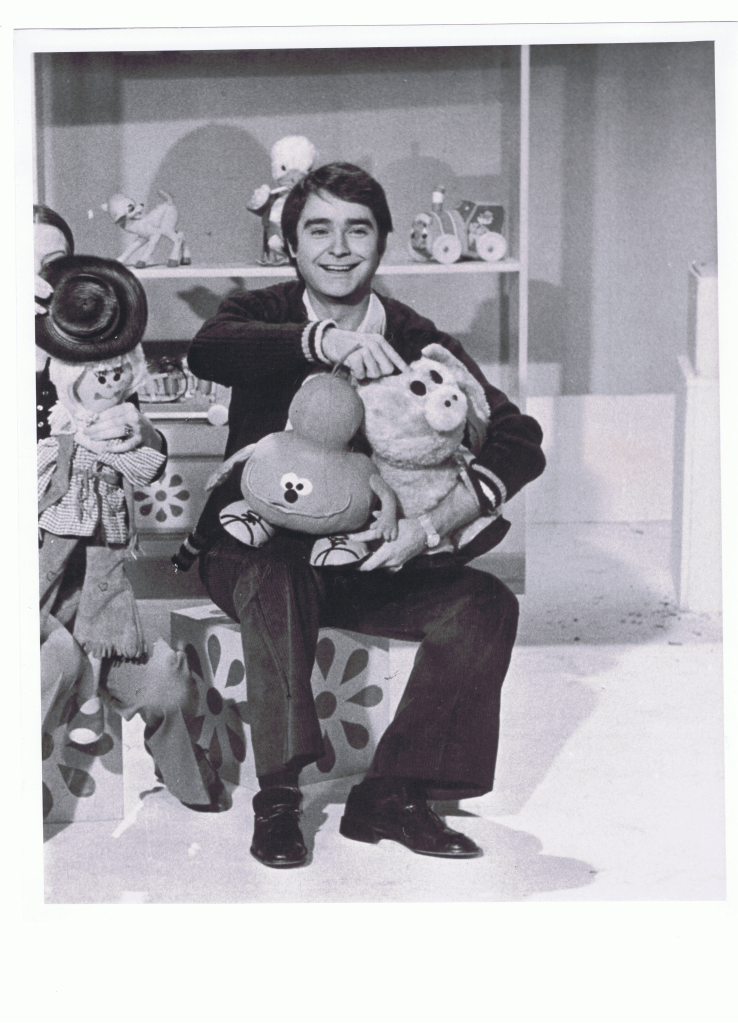

Helen Daniels wasn’t the only Erinsborough regular to appear on the series, either. Here’s Tom “Lou Carpenter” Oliver in 1969. (Tom’s on the left.)

As ever, many thanks to Paul for all the photos and information during the rundown. As mentioned previously, if you want to school yourself to an even great degree in the history of Play School, his Celebration of Play School books one and two are essential texts.

Here he is at ABC Studios along with presenters Alex Papps (2006-) and Rachael Coopes (2011-), from his visit down under in January 2012. Cheers, Paul!

See you again next time with another BBC Broadcasting History InfoBurst!

-

The Two Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes of All-Time: The Grand Final

If this blog has a catchphrase, it must be “that took a lot longer than I’d expected”. And this one did. Not so much as down to getting together a programme history of the show in question, but more to do with checking the broadcast histories of the Top Two programmes. And O! The excitement.

On checking through everything, one programme had a large number of broadcasts missing from the database due to being buried under “Children’s BBC starting with…” billings, with the programme title itself in the RT ‘description’. And so, as we’re talking about a programme broadcast more than 10,000 times, it took a lot of checking to see what hadn’t been picked up. So much so, there was a very real chance this next programme might actually have topped the list.

How close did it come to the top? Well, on my initial recheck, if it had been shown just 26 more times, it would be top of the all-time chart. And then, on checking the other programme left to uncover, it looks like several broadcasts couldn’t be counted (due to actually being an unrelated film of the same name). The gap crept ever closer. After all this time, could it come down to a single figure difference? Or even actually end in a draw?

Then I discovered repeats of The Programme At Number One spent three months going out billed as “NEWS followed by… [Programme Title]”, which increased the gap by a load. Hey ho.

But enough of me explaining why Genome ate my homework, let’s take a look at the programme in second place on the list. Apologies to anyone getting this via email – it’s a long one. It’s time to look through the oblong window at:

2. Play School

(Shown 10,575 times, 1964-1988)

[Many thanks to Paul R Jackson for his help compiling this article, providing a bunch of facts, photos and – marvellously – the quote at the end of the article. Paul is the author of Here’s A House – A Celebration of Play School volumes one and two, so if you’re after a more detailed history of the series, you know where to go. Both are available from the publisher’s website direct: https://www.tvbrain.info/shop]

When launching a television channel, it’s generally a good idea to pick something really good and important to kick things off. Channel Four had the first episode of Countdown, which everyone remembers. Channel Five had the first episode of Family Affairs, which I needed to look up. ITV, of course, had ‘Inaugural Ceremony at Guildhall‘, which can’t have been that good as it didn’t go on to get a full series.

As the BBC’s first new channel since the launch of the Television Service in 1936, 1964’s plans for BBC-2’s launch night were as fancy as you might expect. Following a brief introduction to the channel, there was the promise of new comedy show The Alberts (featuring, as the RT listing had it, “Ivor Cutler of Y’hup, O.M.P, Professor Bruce Lacey, John Snagge, Sheree Winton, Benito Mussolini, Major John Glenn, Adolf Hitler, David Jacobs, Birma the Elephant (by courtesy of Billy Smart’s Circus) and other celebrities“), followed by a production of Cole Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate. Brilliant. Nothing could possibly go wrong.

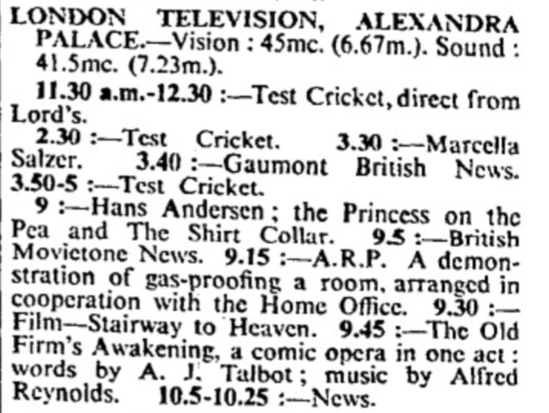

Ah.

As fate would transpire, due to a huge fire at Battersea Power Station a mere half-hour before the channel went live, those plans were thrown into candle-lit disarray, and an expectant audience was instead treated to an (initially mute) news bulletin beamed from the nearby but unaffected news studio at Alexandra Palace, as read by Gerald Priestland. That was followed by an evening of captions and apologies. Most British channel launch ever, 10/10, no notes.

And so, as I’m sure you’re already well aware, the first actual programme broadcast on BBC-2 was something commissioned for an audience of under-fives. And, much like Channel Four’s Countdown, it would go on to a very long life on our screens.

Yep, it’s Play School. For a good few generations of young televiewers, a programme that would provide an early introduction into a long fascination with TV. And, personally speaking, the catalyst to one of my earliest distinct memories. On – I think – turning four, in response being told that I’d been born at 11am on my day of birth, I sought confirmation that “I was in time to see that day’s Play School?” Talk about appointment to view television.

The proposal of having a pre-school series in the new channel’s schedules came from BBC2 Head of Programmes Michael Peacock, and by the time of Play School’s launch, the BBC had a new Head of Family Programmes in place to help get those wheels into motion.

Doreen Stephens had been a hugely instrumental figure within 1960s television. Despite only starting her TV career at the age of 40, she’d go on to become Head of Women’s Programmes at the BBC, then (as just mentioned) Head of Family Programmes, before moving to LWT to head up their Children’s, Religious and Adult Education Programming department. Despite initial reluctance in moving away from Women’s Programmes and onto Family Programmes in 1963, she soon revolutionised the department, bringing in fresh faces and minds to help move away from the imperial-era likes of Watch With Mother and introduce programmes like Jackanory, The Magic Roundabout and Play School.

Stephens’ aim was to move away from cotton-wool content like Bill and Ben, instead introducing shows for a generation who’d soon be thrust into the more technical world of the 1970s. Her approach was a success. At a time when the expanding ITV network was bossing the BBC in the ratings, her children’s programmes consistently attracted more viewers than the commercial channel’s own offerings. Indeed, it was that level of success that saw David Frost lure her over to LWT after landing the licence for London’s weekend broadcasting.

A board chaired by Michael Peacock selected Joy Whitby as producer of the new programme. Whitby was duly given a more-than-modest budget of £120 per week (£2,030 in today’s money) to put together five programmes per week, all to be broadcast live. So, in today’s money, that’s a whopping £406 per episode. An unbilled pilot episode of the programme was shown as part of BBC-2’s trade test transmissions on 31 March 1964, presented by Eric Thompson and Judy Kenny. Coincidentally, the script and programme still exist in the BBC’s archives. Y’know, in case anyone working at the BBC Archives is reading this.

All was set for the launch of the full series. The initial working title of Home School had been discarded before this stage, in favour of the friendlier sounding Play School. As programme advisor Nancy Quayle would later explain in the fifteenth anniversary programme Twenty Five Minutes Peace, “play is the child’s first school”.

One suspects that when Virginia Stride had her audition for the role, she didn’t expect to become front page news the day after her debut. Whitby had initially joined the BBC to work in their School Broadcasting Department, but working on Play School would be the first of several projects that would land her name in British television history. After liaising with a variety of experts in the fields of childcare, learning and literature to come up with a suitable blueprint, it would go on to win various accolades, including a Guild of Television Producers and Directors Award, and a place in the hearts of children for decades to come. Whitby later left the programme to devise Jackanory (as covered previously) before joining Doreen Stephens at LWT in 1967, but as leaving presents go, the format for Play School is hard to beat.

To outline what parents (and their children) could expect from the new series, Joy Whitby took to the Radio Times.

Joy Whitby introduces her new BBC-2 series beginning today which provides ‘nursery school’ for the under-fives

ARE you an exhausted parent of a child under the age of five? If so, Play School may be just what you are looking for. Without actually leaving home, for half an hour every day (from Monday to Friday, beginning today, Tuesday), your child can benefit from the advice of leading authorities on nursery education and enjoy the undivided attention of a changing panel of presenters-young and resourceful men and women, most of them with children of their own. Play School will not be a televised nursery school-room. It will use all the advantages of television to do the job of a nursery school in its own exciting way. Every day our story chair will be occupied by a storyteller of out- standing talent-in this first week Athene Seyler, followed by Charles Leno, Eileen Colwell, and David Kossoff. Through our magic windows we shall invite children to explore the real world which they long to discover-the world of buses and elephants, flowers and snails, rain and shadows. There will be a Pets’ Corner, a Play School garden, songs, and surprises, and opportunities for joining in both new and traditional games. We hope to offer not just another half-hour’s viewing a day. We want the children who attend Play School to take away from it ideas and stimulation to last long after their television sets have been switched off.

Joy Whitby, Radio Times, 18 April 1964

Presenters of that first ever episode: Gordon Rollings and Virginia Stride With the demands of five live episodes per week, running almost every weekday of the year, the decision to use a repertory company of hosts was an obvious one, but each needed to be suited to the role, and the process of getting the right presenters for the programme was delightfully fitting. When Brian Cant, at the time a jobbing dramatic actor, applied for a role in the new series, his audition involved Joy Whitby kicking a box out from under a table and asking Cant to “get in there and row out to sea”. One ad-libbed fishing voyage later, a three month contract on the series was his. Eighteen years later, he would still be a regular Play School player.

In the same way a football squad needs to have a variety of skills and disciplines, Play School’s presenters had a good mix of backgrounds, with Joy Whitby selecting thirteen equally valuable squad members from the off: Virginia Stride and Gordon Rollings (as seen in the first ever episode), Carole Ward, cardboard box interviewee Brian Cant, Judy Kenny, Marian Diamond, Julie Stevens, Terry Frisby (then billed as Terence Holland), the international trio of Rick “Fingerbobs” Jones (Canada), Marla Landi (Italy) and splendidly-named Dibbs Mather (Australia), plus husband and wife Eric Thompson and Phyllida Law. Strength in depth, right at the start of the season.

Each episode had a pairing of squad-rotated presenters, each advised to speak to the camera as if addressing an individual child, an inclusive approach that made viewers feel at home. While the presenting line-up would be freshly rotated, a sense of uniformity was applied each day’s episodes. So, each Monday’s episode would focus on ‘The Useful Box’, Tuesdays would be Dressing Up Day, every Wednesday would focus on pets, each Thursday encouraged viewers to use their imagination, while Fridays would be Science Day.

Another integral part of the new series was each episode’s storytelling segment. Rather than have one of the presenters taking to the storytelling chair each day, a variety of guest storytellers would appear, introducing the young audience to a story, often of their own making. Speaking in 2006 BBC Four documentary The Story of Jackanory, Joy Whitby told of the thinking behind this approach.

“It seemed important to get in and attract people of great quality who might not want to spend all their time doing children’s programmes but who would certainly commit themselves to some performances, and in a way that’s what happened with the storytelling element.”

Joy Whitby, The Story of Jackanory (BBC Four, TX 14/02/2006)And so, starting with actress Athene Seyler in that very first episode, the storyteller segment would soon go on to feature names such as Flora Robson, Roy Castle, Richard Baker, Quentin Blake and a pre-Dad’s Army Arnold Ridley, with many Play School storytellers later going on to perform similar roles in Jackanory.

Interesting to note that Ridley first appeared on BBC-tv in 1936. And also that one of the many stage plays he wrote – Meet Mr Lucifer – was a scathing satire on the addictive nature of television Within the first few months of Play School, a decision was made to expand the remit of storytellers beyond the UK, inviting storytellers from other nations to relate children’s tales from other lands. The practice started in July 1964, with British-Pakistani actor and director Zia Mohyeddin taking to the chair to read a selection of traditional Indian fables.

Daily Mirror, 19 April 1965 The formula was a success with those able to receive BBC-2, so much so that a special edition of the programme aired on its first anniversary in April 1965, with several viewers (and a baby lamb called Sooty) invited to a special tea party at the Riverside TV Studios. However, by that point the reach of the second channel still only extended as far as London, the South-East, East Anglia and the Midlands (with the episode shown on Midlands’ launch day – 23 November 1964 – featuring a bespoke welcome from presenters Marla Landi & Brian Cant).

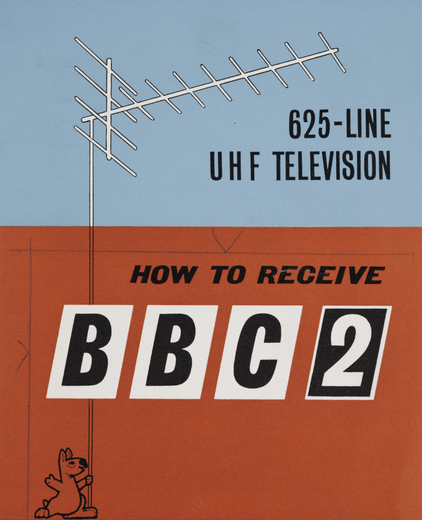

Even then, Play School could only be viewed in homes containing 625-line compatible sets. Viewers elsewhere in the UK were finally able to knock on the Play School door in July 1965, with the first same-day repeat of the programme on BBC-1, initially for a trial period running the length of the summer holidays. Such was the confidence in the trial, the afternoon broadcasts of Watch With Mother were paused to make room for it. A whole new set of children would be getting to see the famous Play School windows.

“Windows ’64.” [Photo courtesy Paul R Jackson] With Play School finally making an appearance in regional copies of the Radio Times that hadn’t been carrying BBC-2 listings, Joy Whitby put together a fresh introduction to the programme, this time being able to include evidence of what they programme had brought to those lucky enough to enjoy it.

For the next six weeks* the afternoon edition of ‘Watch with Mother’ on BBC-1 will be replaced by a repeat of ‘Play School’, the morning programme which is running on BBC-2

Can you remember what it was like to be four years old? Everything you saw was new. But your hands were still uncertain servants. Your feet were not allowed to take you exploring far beyond your own front door. Your mind bubbled with ideas but you did not have enough words to express them. This child you once were is Play School’s target audience.

Turn on your set and you will see – a house. The door opens and lets you into a room which very soon you will feel you know: Humpty Dumpty, Jemima, and Teddy live in the toy cupboard by the blackboard. The shelves are full of books. The picture board might show one of your own paintings one day. There is a corner for pets; a table for scientific experiments; seven pegs carry an ever-changing selection of dressing-up clothes; and a large hamper overflows with useful oddments for making things.

So far Play School offers the standard equipment of any good nursery school. But it also has at its disposal all the imaginative resources of television-lights that can transform a blank wall into an apple orchard, lenses that turn men into giants, film that can show anything from a spider spinning its web to a rocket ship on its way to the moon.

Above all, Play School offers a stream of exciting people-not only experts in the field of nursery education but visitors from the world of adult entertainment. Ted Moult describes his farm. George Melly provides an ABC of jazz. Many accept for the first time the challenge of shaping their material without condescension to the needs of this specialised audience. A team of twelve young men and women present the programmes, pairing up a week at a time with changing partners-a system which keeps the chemistry fresh for viewers and performers.This testimonial from a couple of teachers whose daughter has watched Play School from the start is typical of the many letters we receive from parents: ‘Her imagination has been stimulated, her language enriched and the creative ideas which are a feature of the programme have started her on many an hour of effective learning through play.’

Joy Whitby, Radio Times, 24 July 1965

We hope that this week-with Athene Seyler, Beryl Roques and Brian Cant – what has been true every day for thousands of children on BBC-2 can now be true during the summer holidays for the wider audience on BBC-1.

(*Newspaper reports at the time put the trial run as lasting eight weeks, not six. In the end, the trial ran for a total of eight weeks. Pointing this out doesn’t really add anything of value, but I’ve typed it in now.)Truly, while Open University would go on to become ‘The University of the Air’, Play School was fulfilling a similar remit for pre-schoolers. Avoiding the maternalistic tone of Watch With Mother, this was much closer to speaking to under-fives at their own level – for all that Bill & Ben, The Woodentops or Muffin the Mule had enthralled audiences, there had been a disconnect between the screen and the audience. With Play School, the children were invited to take part, either by sending in pictures in the hope they’d appear on the Play School set, or by playing along with the activities on screen.

Crucially, Play School was honest enough to avoid the assumption the entire audience were on board with the presentation style. As series producer Cynthia Felgate pointed out, “Talking down is really based on the assumption you’re being liked by the child. But if you imagine a tough little boy of four looking in, you soon take the silly smile off your face.”

The high regard that the series was now held in became clear in September 1965. The BBC had made a landmark agreement with the UK’s three main political parties to televise the Labour, Conservative and Liberal Party conferences in full on BBC-2. This was way beyond the scope of any Party Political Broadcast – each day’s coverage was scheduled to run from 9.30am until the close of the day’s play around 5pm. The agreement came with only one caveat from the Beeb: live TV coverage had to be paused at 11am each morning to make way for Play School. Ted Heath nil, Big Ted one.

Play School was back on BBC-1 throughout the summer holidays of 1966, but this time it would be simulcast on both -1 and -2 at 11am each weekday. That’s an impressive feat considering simultaneous broadcasting was an occasion normally reserved for cup finals and royal events, and even then only because BBC-1 and ITV both wanted a piece of the same pie. On top of that, BBC-2 had recently been made available to the majority of the UK, largely meaning only those still using 405-line sets were missing out. Play School was certainly becoming what is known as A Big Deal.

As adoption of BBC-2 increased, Play School was confined to the channel for the next few years, until in November 1968, when Play School started being repeated on a long-term basis on BBC-1 – in the peak post-school time of 4.20pm to boot, albeit only on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays. Tough luck if your home was lumbered with an antique television on the other weekdays, but at least you could spend your Monday and Wednesday afternoons watching vocationally improving fare like Training In Skills or Teaching Maths Today in that same slot. You know, for the really smart under-fives.

By this point, Play School had started going out in full colour on BBC2 (at least on most days, when they were able to use one of the BBC’s colour-capable studios), which helped bring a welcome dash of colour into the worlds of the young audience, and making all that imagination-fuel that bit more vivid.

Many of the cast of presenters would go onto other roles as a result of their time on Play School. Britain’s National Cool Uncle Johnny Ball would move onto a career of winsomely accessible maths, logic and science programmes like Think of a Number, Think Again and the troublingly-titled Johnny Ball Reveals All. The comic chops displayed by Fred Harris led to a brief career change in Marshall and Renwick’s radio comedy The Burkiss Way and LWT’s Burkiss-in-all-but-name sketch comedy End of Part One, before becoming the BBC’s friendly face of computer literacy throughout the 1980s. Meanwhile Brian Cant – long before his memorable stint on This Morning With Richard Not Judy‘s The Organ Gang – moved onto Play School’s first spin-off series, Play Away (broadcast 308 times, 1971-1984).

Play Away was a much, for want of a better word, ‘looser’ affair than Play School, with a heavier emphasis on songs, slapstick and puns than its parent series. As befitting Play Away’s more relaxed aesthetic – a bit like seeing your teacher in the supermarket wearing civvy clothing – it mostly went out on Saturday afternoons, but would get occasional repeats on weekday Children’s BBC, and built up quite a noteworthy cast during its time on air. Regular Play School players were the faces most familiar to the audience, namely Brian Cant (who featured throughout the entire 1971-84 run), Derek Griffiths (1971-73, 1975), Chloe Ashroft (1971-79), Julie Stevens (1971-79), Lionel Morton (1971-77), Carol Chell (1971-80) and Floella (now, of course, Baroness) Benjamin (1977, 1979-84).

There was also room for a fresh intake of Play Away-only players, including (as surely everyone knows by now) a pre-fame Jeremy Irons, but also early gigs for Julie Covington, Anita Dobson, Tony Robinson and Alex Norton. And, despite initially being studio-bound, later series of ‘Away would feature (and heavily involve) an actual studio audience. Plus, the entire run of the series featured Jonathan Cohen heading up the Play Away Band. Quite the ensemble, all in.

Of course, you don’t get anywhere by standing still, and Play School wasn’t afraid to move with the times. For example, the famous title sequence (“Here is a house…”) underwent more regenerations than The Doctor during it’s time on air (well, more or less), the animation often being updated to keep things fresh (if reliably hauntological for much of the run).

And possibly in line with current architectural trends, though I don’t recall a penchant for houses spewing out paint in the mid-1980s. Of course, Play School wouldn’t have been Play School without the involvement of the Play School toys. Inanimate, they may be. Mute, unashamedly so. Integral? Definitely. So, let’s take a moment to mark the input of Humpty (who first appeared in that very first episode on 21 April 1964), Jemima, Big Ted (originally named ‘Teddy’), Little Ted, Dapple the Rocking Horse, Poppy, Bingo the sock dog and Cuckoo. Oh, and not to forget Hamble, terrifying tots since that first ever episode. Co-stars who were at least a little more active were the Play School pets, expertly looked after by Wendy Duggan from 1965 onwards.

Humpty was the best, of course. [Photo courtesy Paul R Jackson] February 1983 saw the introduction of a short-lived companion programme, in the form of Play School Play Ideas. Having originally been a series of spin-off books first published in 1971 (and written by the appropriately-named Ruth Craft), each ten-minute episode ran before regular episodes of the series, but was targeted more at parents who wanted to be ‘one jump ahead’ on some of the ideas from the series. Looking for a choice of recipes for finger paint or play dough? Or a heads-up on the bits and pieces needed to play some of the games at home? Or even some personal feedback from a teacher on the value of the series to nursery attendees? Then this eight-episode series was very much for you.

A larger change came later in 1983, when series editor Cynthia Felgate marked the programme’s move from BBC-2 mornings to BBC-1 mornings (making way for Programmes for Schools and Colleges, which travelled in the opposite direction) by a more literal house move for Play School. A brand new set (sorry, ‘house’), a new theme tune (and accompanying dialogue), plus a switch from two to one main presenter each day, with various guests popping in each week. The new jazzier stylings of the series certainly helped keep things fresh, but time was running out for Play School.

And not just because of EVIL PERILS imposed by the reckless programme (Daily Mirror, Friday 29 Apr 1983) 29 March 1985 saw the last Play School going out as part of the afternoon Children’s BBC schedule, meaning the programme was now a solely morning treat once more, though that was offset by Sunday morning broadcasts of highlights from the previous week. Play School continued in this vein for a few more years (still showing sufficient importance to punch a twenty-minute hole in daily Party Conference coverage each autumn), but there was now an acceptance that slightly older children coming home from school no longer had much interest in the series.

Pretty cool new set, mind. [Photo courtesy Paul R Jackson] When the end came for Play School, it was at the hand of someone who’d been there at the beginning. Anna Home had been a part of the production team right from the very beginning, before moving on to produce Jackanory, plus drama serials such as Carrie’s War, The Canal Children and The Changes. By 1988, Home had become Head of Children’s Programmes, and felt that at the 1990s loomed, Play School was still slightly stuck in the past. Another Play School stalwart delivered the final blow. Cynthia Felgate’s production company Felgate Productions picked up the contract to make the new totem for under-fives: initially called Playbus (later Playdays), which would go on to have quite an impressive run of it’s own. And so, between March and October 1988, a variety of Play School episodes were repeated while energies were concentrated on its successor.

And so, that was the end of Play School. Between 1964 and 1988, it had featured a total of 104 presenters (94 in the original run, 10 in the post-83 reboot), 54 guests, and six clocks. It saw episodes recorded in the Riverside Studios, Television Centre, Lime Grove Studios, Manchester’s Dickenson Road and Oxford Road studios, plus Pebble Mill. It even earned a quartet of repeat broadcasts (all from Christmas 1985) on short-lived digital channel BBC Choice over Christmas 1999 and 2000. Such was the regard the series would still be held in, the Riverside Studios would play host to a Play School reunion in May 2014, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the series. Previous to that, the 2010 Bafta Children’s Awards saw a special award presented to Brian Cant.

Paul R Jackson with presenters Carol Chell, Derek Griffiths and Brian Cant, Riverside Studios, May 2014 [Photo courtesy Paul R Jackson]

Brian Cant and his Plus One for the evening [Photo courtesy Paul R Jackson] Except: it wasn’t quite the end. Such as the success of the series in the UK, overseas broadcasters had been very keen to bottle some of that magic. The Australian version of the programme first aired in 1966, and is still airing on ABC Kids to this day, making it the longest-running children’s show in Australia (and second-longest in the world, after our very own Blue Peter). New Zealand’s adaptation of the series ran from 1972 to 1990, using the original 1964 UK branding for the series throughout.

In colour! Non-English speaking countries also got in on the act, with Switzerland’s Das Spielhaus running from 1968 to 1994, Austria’s Das Kleine Haus (from 1969-1975) and Spain’s La Casa del Reloj all getting in on the act. While some of the remakes were wearing pretty loose-fitting clothing (the Swiss version had talking puppets throughout, which is all wrong), some adhered a lot more closely to the original. Such as the Norwegian version Lekestue, which stuck very closely to the original Play School formula.

With such a rich legacy, it’s comforting to know that Joy Whitby’s original low-budget formula would go on to nurture young minds not just in the UK, but around the world. In fact, it’s probably fitting to give the final word to Joy herself.

“Great to see Play School at number two in your list and to know that Jackanory has also made the top ten. What a wonderful testament to the original team who set the template in 1964. It’s gratifying that the programme continues to hold a place in viewers’ hearts with fond memories of all those talented people, both in front and behind the camera.” (Joy Whitby, January 2024)

So, that’s it. The TV programme shown almost-most frequently within the BBC’s entire history. But what’s at number one? Let’s find out right now, shall we? It’s time to join those…

1. Neighbours

(Shown 10,626 times, 1986-2008)

Oh, the irony. Despite using the title ‘The Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes of All-Time’, the programme at number one was a show originally made by and shown on… Australia’s Seven Network. Not even a BBC co-production. So, it’s really the case that Play School is the most-broadcast BBC programme of all-time. It was just pipped to the post by Neighbours. Which, er, isn’t a BBC programme.

That said, the top programme on the list isn’t entirely divorced from British television. Reg Watson, the original architect of Ramsay Street, had created an impressive roster of continuing drama in Australia, such as Prisoner (suffixed ‘Cell Block H‘ in the UK), The Young Doctors and Sons and Daughters, single-handedly filling approximately 36% of ITV’s airtime between 1986 and 1994. But long previous to all that, 1955 saw a tyro Watson leave Australian shores for the UK, and a role at the nascent ATV Midlands. After an initial spell behind the camera directing fare like Noele Gordon ad-magazine Fancy That, then producing the likes of chat show Lunchbox and Godfrey Winn Speaking Personally, Watson championed a proposal for a new weekdaily soap opera devised by Hazel Adair and Peter Lingset.

It was set in the Midlands region – always handy when ATV needed to prove it wasn’t wholly fixated on its London weekend franchise – and was called The Midland Road. Unfortunately, this was in 1958, when a combination of limited broadcasting hours and moneyed franchise holders determined to get their content on screen meant there was limited space in the schedules. It would take until November 1964 before The Midland Road finally reached TV screens, initially in the ATV Midlands region. That is, once it had changed its name to Crossroads.

It’ll never catch on. Watson produced Crossroads for just under a decade before returning to Australia for a role as Head of Drama for storied soapmongers Reg Grundy Productions. The person responsible for that move? Bob Monkhouse. Yes, really. Well, kinda.

During Watson’s time working for ATV, a certain Mr Reg Grundy was enjoying his Mayfair honeymoon with his bride, Joy Chambers-Grundy. During that spell, the newlyweds met with expatriate and future TV-am tyrant Bruce Gyngell, then working for ATV. Gungell introduced the couple to current ATV big draw Bob, who invited the Grundies over to his St. John’s Wood home for dinner. Ever the gracious host, Monkhouse followed this up with an invitation to ATV’s studio to attend a recording of his hit series The Golden Shot, but not before treating the couple to dinner at the Albany Hotel. To make them feel at home, he also invited along a couple of Australian expats working at the channel – Golden Shot director Mike Lloyd, and… Reg Watson.

The Regs immediately hit it off, and with Grundy planning the formulation of a drama department within his media empire, Watson gave his new friend a crash course in putting together a successful serial. Subsequent trips to the UK saw Grundy seek out Watson for added guidance and advice. The guidance was even more pressing once Grundy’s first proposed drama serial – Class of ’74 – was being devised, mainly by staff more used to working on game shows. Grundy would collate together scenes from the series and get them over to Birmingham for Watson’s input. While Watson’s long-distance advice was valuable, the communications network of the mid-70s was hardly instant.

It’s like a Zoom call, but you have to draw what you think the other person looks like and it costs £7.56 per minute Ultimately, Grundy flew back to the UK to try and coax Watson back to his motherland, if only for as long as it took to help with a flailing Class of ’74. His mission helped by the fact Lew Grade hadn’t got around to renewing Watson’s contract, Grundy offered Watson a much more generous lifestyle than the notoriously penny-pinching ATV, and an initially sceptical Watson agreed to switch 1970s Birmingham for Sydney’s Bayview.

I mean, there are more difficult dilemmas. By the 1980s, Reg Grundy Productions (or as it now was, ‘The Grundy Organization’) was responsible for around 25 hours per week of content on Australian TV – a remarkable amount for an indie production company. In addition to soaps, Grundy quiz shows – both homegrown and adapted from overseas originals – were peppered throughout the TV listings, with Sale of the Century, Ford Superquiz, The New Price is Right, Family Feud, $100,000 Moneymakers and Wheel of Fortune attracting loyal audiences.

That’s a real car, the hosts are actually huge. The Organization (yes, with a ‘z’) also made the move into foreign markets, setting up offices in New York, LA, Hong Kong and London, producing programming for local networks. Beyond TV, the GO had moved into areas such as travel, restaurants, a record label and radio. Basically, with noses in all manner of businesses, the many-headed Grundy business hydra seemed to be unstoppable.

For the drama-based portion of this success, credit goes to Reg Watson’s uncanny ability to devise winning drama formulas. Albert Moran’s book Images & Industry: Television Drama Production in Australia (Australian Screen, 1985) put Watson’s wizardry into context, with some quotes from an unnamed producer within Grundys:

Take Prisoner, for instance. Grundys were approached by Channel 10: “We’re interested in a show, we’d like something vaguely prestigious, Australian oriented. We want it to run one hour per week for sixteen weeks and then we’ll stop.”

So [Ian] Holmes or Reg Grundy gets on the telephone and rings Reg Watson and says, “I’ve made a deal – quick, think of something.” So Reg with his instinct for the audience goes to work, sweats a lot and tears his hair out, goes even greyer and comes up with three or four ideas that he thinks will work. And he puts them to the channel. The Channel picks one and says: “Yes, we’ll go with this.” They ring up. The whole organisation goes into a panic. “They’ve picked X, what are we going to do?”

It’s at that point that Reg sits down at his typewriter and tries to think up a plot to fill in the concept… he wrote a plot for the first episode that was full of short zappy scenes, zappy to stop you thinking about any of them, seventy zaps in forty-five minutes. And then hacks like me are left to make it credible.

Images & Industry: Television Drama Production in Australia, 1985Watson’s transcontinental transfer to Grundys had certainly been a timely one. With Class of ’74 already on air by the time he arrived, the problems with the series were clear (despite early rushes being flown to Birmingham for input from a Watson working through his three months notice). Despite attracting a lot of initial attention, ’74 (later renamed Class of ’75) would see a swift ratings decline and be axed within 18 months. Conversely, The Young Doctors, the first drama serial to be devised under Watson’s tenure, would run for seven years and 1,397 episodes. That was followed by 1977’s The Restless Years (four years, 780 episodes) and 1979’s Prisoner (seven years, 692 episodes). It soon became clear that the ribbon in Watson’s typewriter had been personally inked by God.

In Reg Grundy’s autobiography, the TV mogul refers to the hiring of Reg Watson as “the most important appointment I ever made”. One example of typical Watson foresight came when Watson floated an idea about a new serial to Grundy: “I’ve got this idea for a drama about three families. The whole concept is about communication between the generations.” From small acorns, eh? And indeed, despite the common conception many held about Neighbours (yes, we’ve got there at last), it was a boundary breaking premise in many ways. Borne of Watson’s time working on Crossroads – and his admiration for Granada’s Coronation Street – this was a programme that would become, at least to British eyes, the quintessential Australian drama series.

And not actually all like this. (The Kenny Everett Television Show, s5e1, 30 November 1987) And while the programme itself would soon evolve, that principle of focusing on Ramsay Street’s three families would remain key. One such family was led by self-employed plumber Max Ramsay, whose grandad gave the street its name; next door is widower Jim Robinson, raising four kids with the help of mother-in-law Helen. And, aside from the feuding Ramsays and Robinsons, the third focal point of Ramsay Street was the home of twentysomething bachelor Des Clarke, who’s just rented a room to Daphne Lawrence, who, it turns out (cover your children’s eyes) is a stripper. The Sullivans it ain’t.

As Watson himself would go on to point out, “it changed the way we thought in serial drama. In one of the opening episodes, the grandmother was painting and the grandson was sitting for her. He casually said to her, “Grandma, when you and Grandpa were dating, did you have sex?” Normally, we would have her throw the paintbrush down and say, “Look, I don’t want to discuss this”, but we went the other way and she discussed it with him very sensibly.”

Having been bought by the Seven Network, the new series started promisingly. At least, it did in Melbourne, the setting for the series and focus of Australia’s TV industry. It fared less well in Sydney, where slipping ratings saw it moved from a 5.30pm slot to an earlier home at 3.30pm – hardly ideal for the multi-generational audience the programme was hoping to attract.

[Photo courtesy Paul R Jackson] Then, something surprising happened, especially for a show devised by Reg Watson: the series was cancelled by Seven, after just 170 episodes. Then, as far as the Australian TV industry was concerned, something even more surprising happened – this supposed flop of a serial drama was picked up by rival network Ten.

Canberra Times, Sun 15 Sept 1985 The move was far from straightforward. Despite supposedly no longer wanting anything to do with the series, Seven threatened to sue Grundys over selling a series the network claimed to own the rights to. On top of all that, an accidental fire had destroyed the permanent sets used for the series. Any legal issues were eventually settled, and the series was given a more youth-focused revamp before arriving on Ten, at a much friendlier time of 7pm.

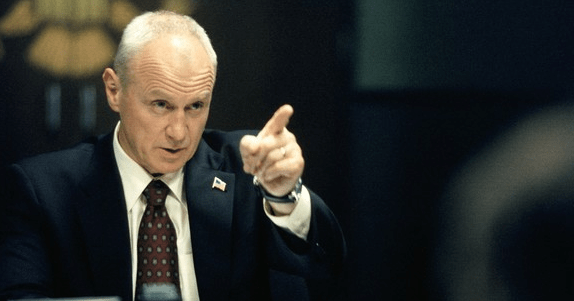

The revamp saw new characters, new sets and a cast comprised mainly of unknowns, such as Jason Donovan, Guy Pearce and Kylie Minogue. Whoever they are. Plus, it kept key actors from the original incarnation of the series, such as the actors who’d go on to play Vice President Jim Prescott in 24, scheming Yorkshire industrialist Charles Widmore in Lost, Secretary of Commerce Mitch Bryce on The West Wing and the Australian ambassador in Flight of the Conchords. Or, if you prefer, Alan Dale.

And, chronologically speaking, this is where the BBC comes in.

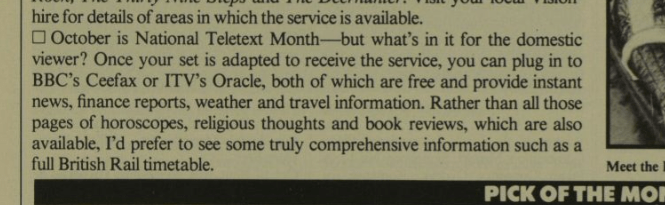

Previously, if there had been anything being shown on daytime BBC1, it would be Programmes for Schools and Colleges, the News, programming for pre-school children, Welsh language content (at least until S4C came along) or Pebble Mill. Occasionally, there’d be live sport, or a political party conference, but aside from that, it would generally be the test card (or Pages from Ceefax by the early 1980s) taking up those afternoon broadcasting hours. That was even the case after broadcasting hours were relaxed to allow for a daytime TV service, meaning ITV franchises were free to put out uninterrupted programming from early morning to late night from October 1972. But, without the increased ad revenue of their rivals, the BBC largely kept away from uninterrupted daytime TV for more than a decade.

It didn’t work out too badly for the commercial channel. A guaranteed 100% audience share for most of each afternoon probably didn’t hurt. By the mid-1980s, BBC1 at least had Breakfast Time to attract an early audience, and gradually, more programmes began to grout the gaps between the end of breakfast TV and the early afternoon Play School repeat, especially now the Schools programming had moved over to BBC2.