-

Splashdown! It’s The 100 Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes Of All Time (14 and 13)

It’s Saturday. It’s 12:15pm. The Weatherman just told us how rubbish the weather this weekend will be, so it’s time for… um.

14: Escape to the Country

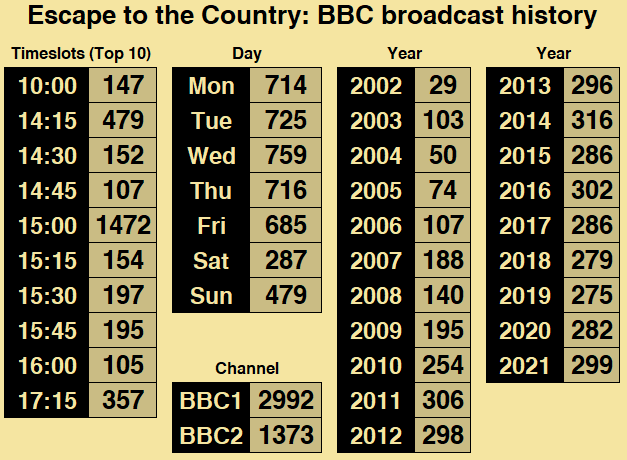

(Shown 4365 times, 2002-2021)

Richie: “Still, I did my bit for the country.”

Eddie: “What, you stayed in the town?”

Richie: “Absolutely.”

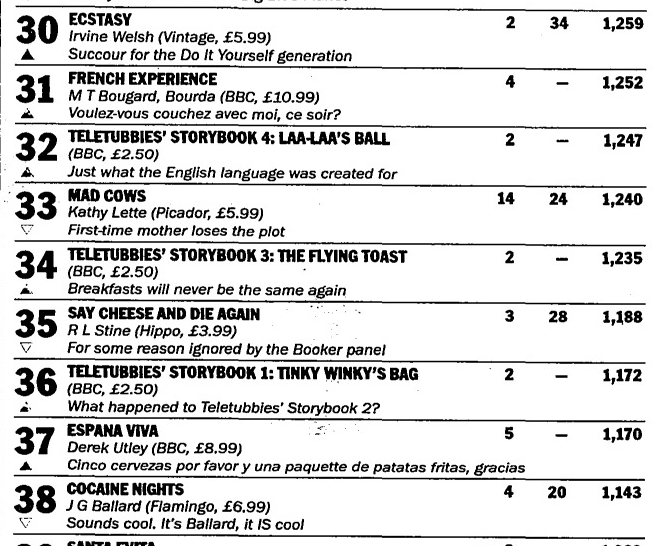

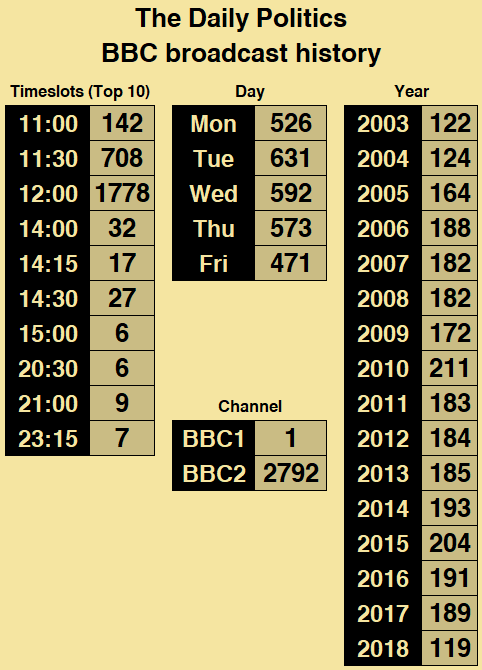

Now admittedly, and it might be my own personal circumstances at play here, but it does seem like the much of this chart falls into one of two categories. Category One is all the programmes that have been part of the TV landscape throughout what feels like our entire lives: your Panoramas, your Matches of the Day, your Songses of Praises. Category Two comprises programmes that seem to have amassed a huge episode count seemingly out of nowhere, mainly due to the camouflage of being on when most people are at work, college and/or school. That category includes The Daily Politics, Ready Steady Cook, Cash in the Attic and this next entry on the list.

For those who usually find themselves working/learning/sensibly doing something else when it’s normally on, Escape to the Country falls firmly into the Someone Buying A House And Maybe Living In It genre, and as these things go, it’s a pretty big deal. Generally, the action involves potential home buyers tiring of life in the Big City, and are surprised to learn that their two-bed London terraced home is worth a cajillion pounds, so they’re off to buy something massive near some fields.

I mean, very nice, but how fast is the broadband there? The buyers will look at three or four suitably sprawling properties in their chosen location, including one ‘mystery house’ chosen by the production team. SPOILER: The mystery home isn’t haunted or anything fun like that, it’s basically just Another Very Nice House But The Kitchen Is Upstairs Or Something. Once all that’s done, the buyers are asked to guess the asking prices of each house, the real asking prices are revealed, and they’re asked to reveal which one they’d like to buy. And sometimes they do, which provides some material for a future episode.

As far as I’m personally concerned, it’s something to angry up my blood as I spend an unhealthy amount of time working and still need to consider selling an internal organ whenever it’s time for a big supermarket shop. However, for many it’s clearly a lovely little slice of afternoon escapism. Not everyone is cynical as me, and feels happy for some people who can sell the Balham semi they paid £3000 for in 1978 and can subsequently afford to buy a third of Leicestershire. And that’s only partly a lazy assumption, by the way. The Independent on Sunday picked out the first episode as a Pick of the Day back in October 2002, their write up casually mentioning “an extended family from Basildon, who have a budget of £600,000, are looking for a mansion in Derbyshire”. Ooh, let’s all root for the plucky ragtag family. Collective prayer that they get a mansion they like, everyone.

But anyway.

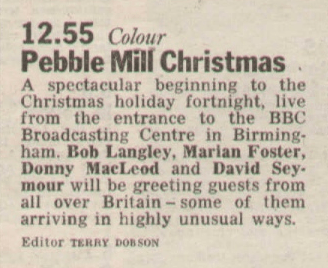

The programme began all the way back in October 2002, in a mid-afternoon BBC2 slot, arriving with the following billing in the Radio Times:

Hoping to “go green”, a young London couple want a country house. Catherine Gee gives them some options, in the first of a new series in which city-dwellers wanting to move to the country are found homes.It would quickly go on to become a regular for the channel, proving popular enough to receive a short repeat run on weekday morning BBC1 in the run-up to a new series in October 2004. At the time, the premise of the programme focused on families looking to leave behind the urban rat race for a rural idyll, but much of the initial ‘action’ involved the potential buyers viewing potential homes on a laptop in their city house, picking a pair of dwellings to visit in person, along with a third ‘mystery’ house. Ooh, mystery house, that’s a bit spooky… oh, it’s just that one bedroom is behind a big curtain.

From the sixth series onwards, all four potential homes would be viewed in person by the buyers, along with a ‘taster’ day where the contributors are invited to sample delights of the local community, learn a little about the area and visit a few local attractions. A few series later, the number of homes was reduced to just three – retaining, obviously, The Mystery House (attic smells of tuna, third bedroom exists only in two dimensions, etc). And that’s where the format pretty much landed for the final time – it’s stayed that way ever since.

In September 2012, as Escape to… neared its testimonial anniversary, first-run episodes were promoted to plum afternoon slots on BBC One, though revised repeats of the series had been airing on BBC One in a similar slot since 2009. In fact, the programme has been the initial beneficiary of BBC One ending the channel’s long-running Children’s BBC strand, which had been in place since the early days of the Television Service, that first non-CBBC late afternoon schedule in December 2009 dominated by a young couple’s quest to find an East Sussex home with a suitably huge kitchen.

Such longevity would usually generate a spin-off or two, and that’s very much the case with Escape to the Country. January 2017 saw the first episode of catch-up series I Escaped to the Country, with currently in its seventh series, and there was even a variant looking at those lucky enough to escape Normal Island in 2014’s Escape to the Continent. And, if rural living doesn’t butter your crumpet, 2019 saw the first episode of Escape to the Perfect Town, catering for those who get antsy if they wander too far from a Tesco Metro.

There’s even an Australian version of the series, Escape from the City airing on ABC from 2019. Indeed, the original UK version is popular enough in the antipodes to have warranted a pair of Region 4 DVDs from Aussie disc supremos Shock Entertainment – a pair of box sets totalling nineteen discs.

“Quality of life, Stu.” It’s even made a (modest) impact in the US, with the programme having appeared on US Netflix and Prime Video. Not a bad feat getting traction where huge houses are largely the default setting in all but the bigger cities, but it’s in the UK where Escape to the Country is truly an immovable feast.

13: Grandstand

(Shown 4500 times, 1958-2007)

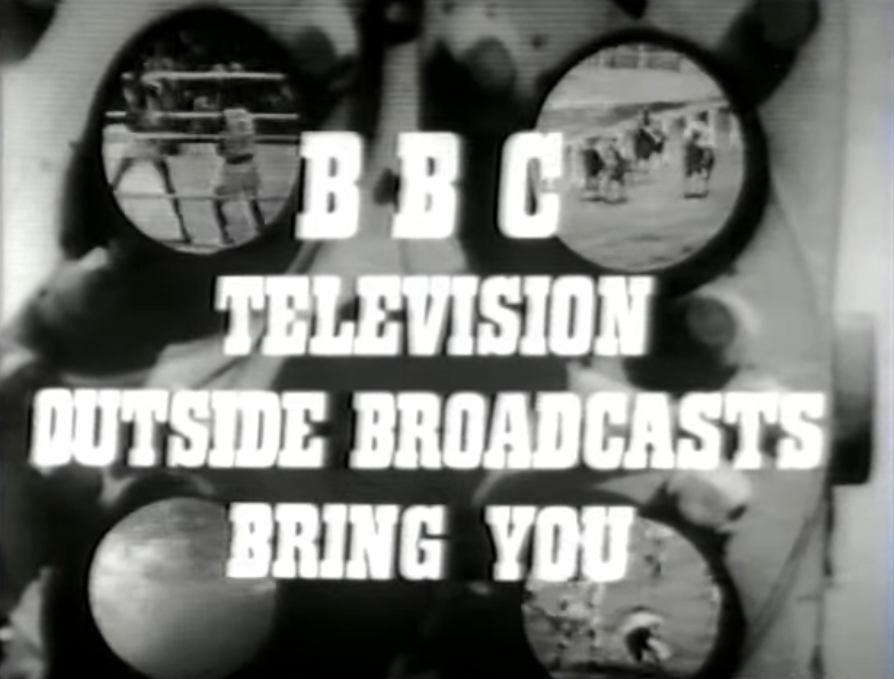

By the 1950s, the BBC Television Service had a problem with sport. Basically, it kept bursting out everywhere – especially on Saturdays – and it HAD to be contained. 1954 had seen the introduction of midweek sporting roundup Sportsview, which arrived with a mission to enthral viewers with the latest news, views and personalities from the world of sport. All very good, but with a runtime between twenty and thirty minutes on any given week, there was only so much room for actual sporting action. Conversely, on Saturday afternoons there was lots of space to broadcast live sport, the resulting BBC-tv schedule akin to a bull let loose in a Sports Direct. Sport was ruddy well everywhere. Live sports coverage was exempt from the Postmaster General’s broadcasting hours restrictions, so Saturday afternoons were pretty much a Linekeresque tap-in for BBC schedulers.

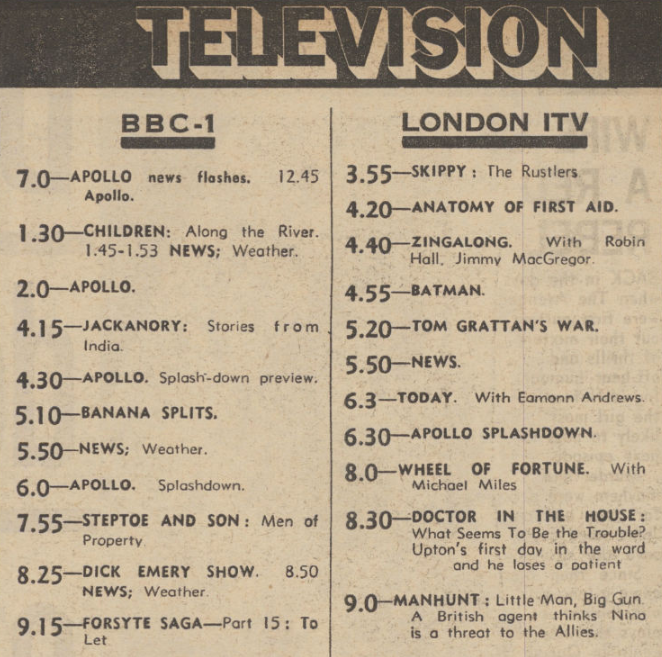

Picking a Saturday at random to give an example, 8 September 1956 saw the following schedule in the Radio Times:

1.50pm: Twenty minutes of Motor Racing from the British Automobile Racing Club’s September Meeting at Goodwood, including The Madgwick Cup, a five-lap race for cars up to 1,100cc. But no time to focus on that, because at 2.10pm viewers were whisked away to the Derby Baths in Blackpool for the National Swimming and Diving Championships. But don’t get too attached to that, because at 2.25pm we’re back off to the Motor Racing for twenty minutes, then back to the Derby Baths at 2.45pm. Who will win the big prize there? You’d better hope it’s decided by 3pm, because then we’re off to Farnborough for an Air Display by the Society of British Aircraft Constructors.

Phew, eh? There really should be a little more order to this kind of thing.

Luckily, a set of steady hands were on the way to steady the Saturday sporting tiller. Programme editor Paul Fox, production assistant Bryan Cowgill and presenter-cum-head of Outside Broadcasts Peter Dimmock had all worked wonders within the BBC’s Outside Broadcast team, Fox having created and edited Sportsview (plus the annual BBC Sports Personality of the Year, originally known as Sports Review of the Year), while Dimmock had proved his broadcasting mettle by taking charge of the BBC-tv’s coverage of the Queen’s Coronation, as well as working as main presenter of Sportsview. But it was Cowgill who had an idea that would transform weekend television for decades to come: an umbrella approach to the Saturday sporting portfolio.

Mind you, Peter Dimmock wanted it to be called ‘Out and About!‘, so nobody’s perfect. Peter Dimmock’s stock was certainly high at the time. In the run-up to ITV’s big launch in 1955, the new network had been prepared to offer hefty pay increases to coax the BBC’s top talent over to the Light Network. Then-DG Sir Ian Jacob, displaying the sense of stoicism and stinginess you’d expect from the BBC of the 50s, was largely reluctant to match any such offers, him being well aware that the BBC’s more limited budget would necessitate cuts elsewhere offset any pay jumps.

That wasn’t the case when Director of Television Sir George Barnes rang up to let him know about ITV’s approach to Peter Dimmock. The response from the DG was definitive: “Make any sort of personal relationships for him – as a personal case – that are necessary.”

That was a decision borne of much more than keeping that friendly sports presenter on screen. Dimmock had displayed a special skill in negotiating sports contracts, and in selling the BBC programmes those contracts generated to overseas broadcasters. He’d also built up a series of working relationships with various sporting authorities, which combined with his ease at presenting live sport coverage made for a pretty comprehensive package. On top of everything else, he headed the BBC’s Outside Broadcasts Department, and had served as Sports Adviser to the European Broadcasting Union. If he hopped channels, any replacement would need one hell of a CV.

Dimmock’s experience at working with the Outside Broadcasts Unit would be essential. He’d been a key component in TV coverage of the Queen’s coronation in 1953, serving as producer for coverage of the Coronation Service from Westminster Abbey, having worked closely with sceptical Abbey personnel to prove that the presence of TV cameras need not be a distraction from the main event. Before then, he’d worked on the 1948 Olympics, the first international relay from Calais in 1950 and the funeral of George VI in 1952.

Having been so instrumental in several of the biggest moments in BBC-tv’s life thus far, throwing to live racing from Haydock was hardly a herculean task. Having seen teleprompters in use during his time in the USA, he know how to get the best out of the nascent tech while live to air. In short, the only person who could hope to keep all the levers moving when it came to launching the BBC’s new, sprawling and enthralling Saturday spectacular: Grandstand.

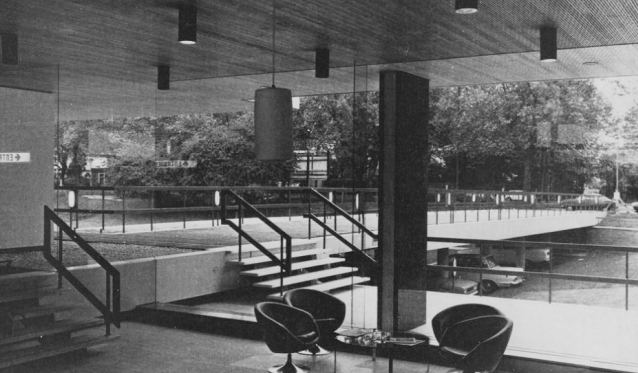

Arriving on Britain’s screens for the first time on 11 October 1958, this was to no small undertaking. A shade under three hours of live television each Saturday, mostly, though not exclusively, devoted to sport – this was a programme from the BBC Television Outside Broadcasts department, after all. Paul Fox took to the Radio Times to explain just how it would all – hopefully – come together, promising that “all the items that used to appear here and there on Saturday afternoons will now come under the Grandstand umbrella”.

With Dimmock at the controls from a swanky new studio at Lime Grove, at least for those first few weeks before his co-anchor – a tyro David Coleman – took sole charge of presentation (allowing Dimmock to move behind the scenes), there were football newsflashes, racing updates (complete with the latest odds), and updates from reporters all around the UK. Fox promised that “sports news of the day will be given as it happens – and, whenever possible, where it happens”, thanks to that BBC Outside Broadcast unit. There was the promise of live horse racing each week, live swimming, motor racing, ice skating and table tennis in the coming weeks. Some of those admittedly easier to capture on camera than others.

There was even the tentative promise of (“if our hopes are realised”) live boxing. But, slightly surprisingly, the callout event on the big preview of Grandstand was… snooker. Not the most obvious draw for the black and white tellies of the time, but this was no ordinary event – Joe Davis, the “greatest snooker player of all time” had signed up for a series of special challenge matches at venues around Britain, taking on top players of the day, such as Walter Donaldson and John Pulman. And, to make it even more of an occasion, Joe’s first match would be against brother and fellow pro Fred Davis.

The action wasn’t just restricted to That England, either. The BBC’s Scottish Outside Broadcast Unit (a branding that conjures up a certain stereotypical image, unless it’s just me picturing an OB van bedecked in tartan) would be on hand to capture action from the World Amateur Team Golf Championship from St Andrews.

It’s fair to say that was a lot to be going on with. The only real hitch was a TV schedule that insisted subsequent children’s programming start airing at 4.45pm, a time which neatly clashes with all the sports results Grandstand would really quite like to tell viewers about. It took until April 1959 before those fifteen critical minutes were finally added to Grandstand’s runtime, allowing for a full Sports Result Service, and an easier route for participants in the football pools to learn they’d need to work for at least another week.

As mentioned, the whole affair being centred around the Outside Broadcast Unit rather than sport specifically gave the programme freedom to wander from its core remit if circumstances required, such as the Henley Regatta or sundry Car Shows. A prime example of this came on 22 February 1964, and an edition promising “the return of the Beatles to the UK, as well as horse racing and rugby union”.

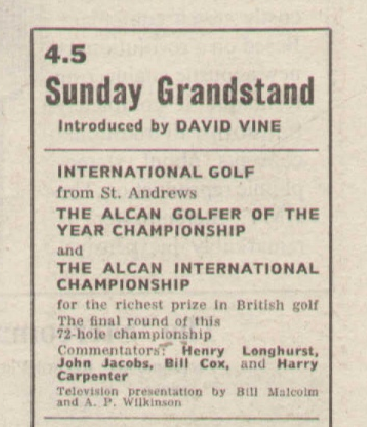

“Ringo! Ringo! Have you heard? Clyde vs Cowdenbeath was postponed!” Unsurprisingly given its position on this list, the programme was a success. So much so, the Grandstand branding swiftly swallowed up key events on the sporting calendar. Alongside regular Saturday afternoon Grandstand, the Radio Times would trumpet the presence of Derby Day Grandstand (from 1960), Cup Final Grandstand (from 1965), World Cup Grandstand (from 1966), Olympic Grandstand (from 1968), and Ryder Cup Grandstand (from 1993), many of which didn’t even air at the weekend. The slow creep of sporting endeavours into the Sabbath also led to occasional airings of Sunday Grandstand from 1967 onwards.

It wasn’t until May 1981 that Sunday Grandstand became a regular fixture, a switch to BBC2 providing the freedom to stretch into the evening schedule. However, the most thrillingly-titled variant was set to arrive on the evening of Tuesday 21 April 1970, where a special edition (step aside, Sportsnight) featured the big Joe Bugner v Ray Patterson boxing match in London, followed by “Apollo 13 Splashdown”. Yep, the return to Earth of moon men James A. Lovell Jr, John L. Swigert Jr and Fred W. Haise Jr led to the programme being rechristened Splashdown Grandstand for a single edition. Just look at this planned programme schedule for the night:

8.0 International Professional Boxing: Joe Bugner v Ray Patterson

8.45 The Main News With Kenneth Kendall

9.0 Apollo 13 Splashdown

9.02 Re-entry due

9.11 Parachutes open

9.16 Splashdown

10.10 On Deck

10.15 International Match of the Day: England v Northern IrelandEpic. Except, of course, a set of fuel cells 180,000 nautical miles from Earth had other ideas. The return flight of the Apollo 13 crew had to be frantically rearranged for the previous Friday, and one of the most exhilarating live broadcasts of the entire space race took place then instead.

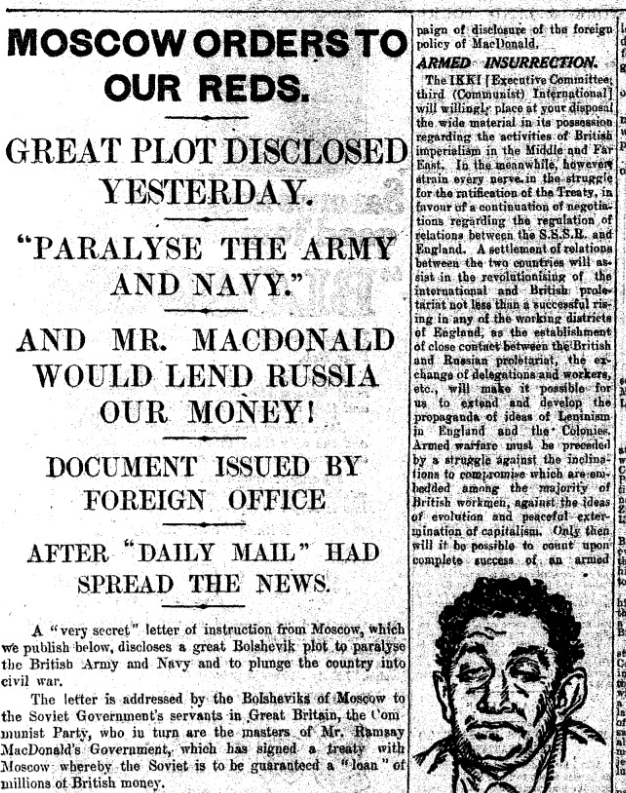

Daily Mail, Fri 17 April 1970

Daily Mirror, Fri 17 April 1970: The Real Splashdown Schedule All very well, but what of our Splashdown Grandstand? Those midweek sporting events instead went out as individual programmes, with the scheduled Splashdown programme replaced by The Dick Emery Show and a rescheduled 24 Hours. Ah, well.

Rewinding slightly, by 1965 Grandstand had a rival on the other side. ITV’s initial reticence to sport receding to make way for World of Sport, which was now very much in play. But while their rival had the winsome Dickie “Last Time I Saw Something Like That The Whole Herd Had To Be Put Down” Davies at the helm, the BBC still held the rights to all the key events, and with Frank Bough sharing hosting duties with David Coleman (the latter frequently off displaying his commentary chops), there was still only one destination for the serious sports fan. World of Sport had Canadian log rolling, Grandstand had Eddie Waring, Football Focus and the Vidiprinter. It was no contest. Especially as Grandstand would be the go to destination for getting those all-important results come 4.45pm. Even now, people of a certain age can only read the Classified Football Results with a particular intonation in their heads.

By the 1980s, a bejumpered Coleman was more at home behind a Question of Sport desk, and with Frank Bough occupied in a similarly wooly vocation on Breakfast Time, it was time for TV’s Mr Unflappability to shine. Step forward Des Lynam. Never had helming several hours of live television on a weekly basis – imagine an election night every seven days, basically – seemed so ruddy effortless. And so, by the late 1980s, Grandstand was cock of the walk. World of Sport had ceased to be, with ITV spending more energy on snaffling exclusivity on individual sporting events – think The Football League, Athletics and Horse Racing – but Grandstand’s greatest foe, and ultimate conqueror, was about to appear from the Sky.

The early days of satellite broadcasting had been no threat to the main broadcasters – nobody was breaking into a sweat over the Screensport Super Cup – but by the mid-1990s, Sky Sports had the budget and the broadcasting bandwidth to do everything Grandstand couldn’t. It could continue live coverage of golfing tournaments, rugby matches or tennis opens way into primetime, with no pressing need to halt coverage in favour of Steve Wright’s People Show or Big Break. And as the pot of available events began to empty, the BBC needed to make more of what it still had. Would people be tuning into Grandstand and hope they enjoyed what they found there, or would they be more enticed by a programme listing for a live Six Nations match?

In the digital EPG age of the noughties, viewers didn’t want to just see that a sprawling Grandstand strand was on, they’d want to know which sport to expect and when. A brand that was once spread across the BBC like sporting butter seemed to be little more than an anachronism kept around out of loyalty more than practicality, and in January 2007 it finally bowed out. By the time of the final Grandstand programme listing, pointing viewers toward the Red Button and BBC website for uninterrupted coverage of the Australian Open or European Figure Skating Championships was the norm, it was clear how the linear Grandstand strand wasn’t really needed any more. The fact that much of that final Saturday edition was shovelled onto BBC2 to make way for a live FA Cup Match of the Day between Luton Town and Blackburn only underlined how inessential the once hardy old brand had become.

Then, it was gone. Broken up for scrap. The following Saturday saw Football Focus officially span off as a standalone programme (which, as far at Electronic Programme Guides had been concerned, it had been for a while anyway), as was the BBC’s Six Nations Rugby coverage. Final Score had the same treatment, once an integral part of Grandstand, now a plucky stat-based orphan left to flourish on its own.

And do you know what? It was fine. When there wasn’t any big sporting event to show on a Saturday afternoon, the BBC no longer felt the need to fling on something sporty for the sake of it. This was an era where Sky Plus was king of the living room. People wanted to be able to record ‘Rugby League’, ‘Swimming’, or ‘Golf’, not use up a valuable chunk of their PVR’s 20GB capacity on several whole hours of sport because that’s how the programme guide had wanted it.

This was the future.

And yet, in a way, it was 1958 all over again.

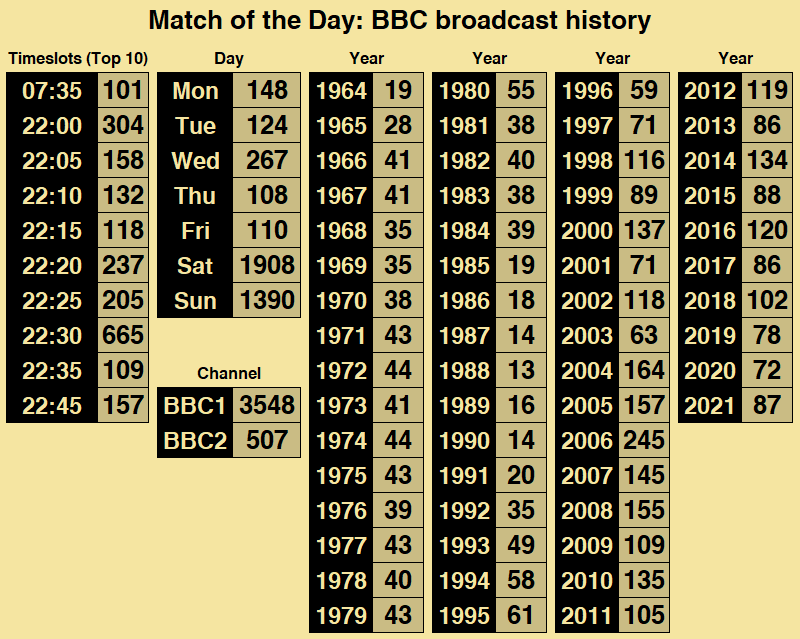

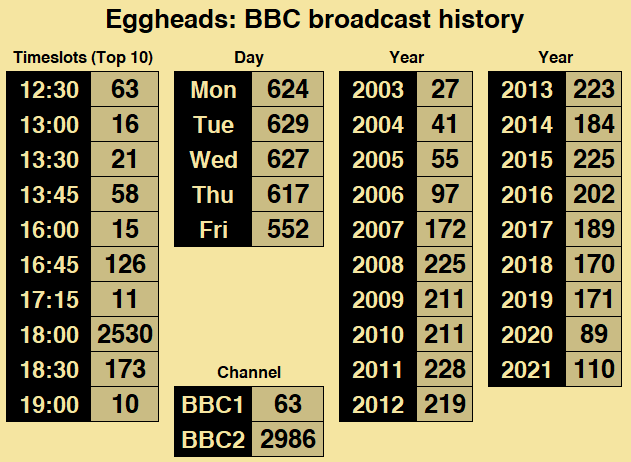

NOTE: Updated figure and table on 16/7/23 to correct the episode counts for 1965 and 1966, plus totals, accordingly. Thanks to eagle-eyed reader @michael_sas for spotting the discrepancy.

There we go, another one out of the way. Phew. Next time: we brush the quivering brim of the Top Ten. Ooh, eh?

Of course, a photo of 70s Des is enough to send anyone’s brim a-quivering. -

Paging Dr Clitterhouse! It’s The 100 Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes Of All Time (16 and 15)

“We interrupt this programme to bring you a football game.”

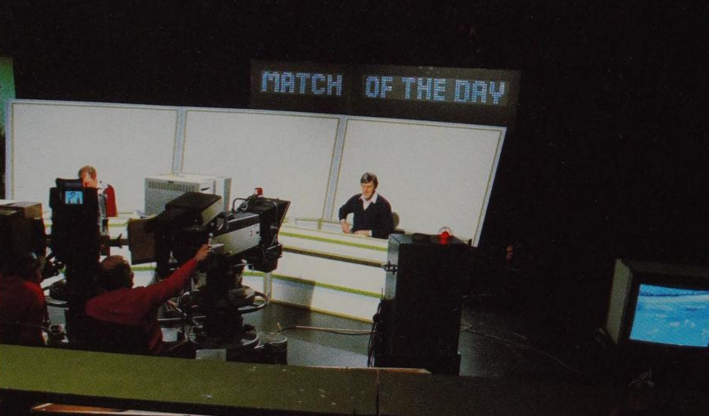

16: Match of the Day

(Shown 4055 times, 1964-2021)

Well, here’s one that was always going to appear, and one where I probably need to clarify the criteria for inclusion. In general with this list, where something had specific programme branding applied to it and it keeps to the core format of the programme, I’m counting it. So, Nationwide Election Special counts, Tweenies Songtime doesn’t. Postman Pat Special Delivery Service please step forward, This Morning With Anne and Nick’s Live Autopsy Hour not so fast.

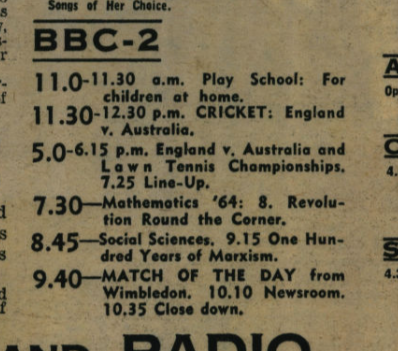

That gets a little more complicated with Match of the Day. For one thing, the first eleven times the title ‘Match of the Day’ appeared in TV listings, it had absolutely nothing to do with football. While MOTD as we’d come to know it first aired on Saturday 22 August 1964, Match of the Day first appeared as a programme title a whole two months earlier. A total of eleven editions of ‘Match of the Day’ aired in relation to the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Championships in 1964 before the moniker was first applied to kickball.

The MOTD branding would go on to become closely aligned to both football and (during Wimbledon fortnight) tennis highlights, with the latter sometimes made clear in the programme title (as Match of the Day from Wimbledon or Wimbledon [YEAR] Match of the Day), but sometimes not.

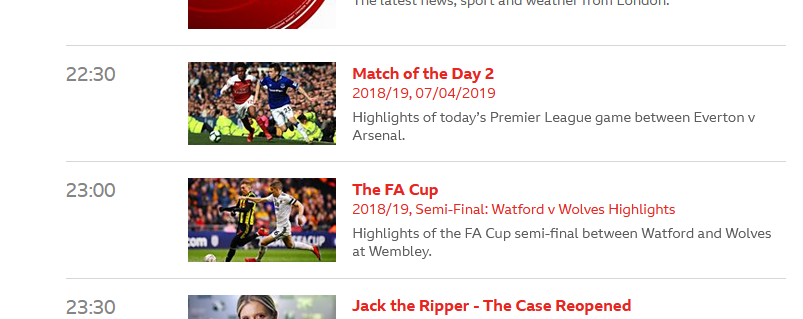

The other complication comes in defining what makes up the ‘core’ MOTD experience. Saturday night football highlights are the main thing you’d associate the brand with, but it’s also been used for live football coverage (sometimes as Match of the Day Live, International Match of the Day or Match of the Day: The Road to Wembley, sometimes as just plain old Match of the Day). And what about Match of the Day 2? Does that count? How about Match of the Day Greats, or …Kickabout, or …Top 10? How about lockdown gap-filler Match of Their Day?

Right, to try and get some kind of vaguely accurate figure here, I’m going to go with the following rule: If it’s tagged as Match of the Day, and the bulk of the content is footage from a football match (or matches, either live or highlights) of a contemporary match, it counts. If it’s not one of those things (so, Kickabout et al), or doesn’t have the MOTD branding, it doesn’t count. Settled? Good.

The waters are, of course, further muddied by the MOTD branding not always being used in programme listings. Since 2014, much of the BBC’s live or highlight coverage of The FA Cup has been billed as ‘The FA Cup’, keeping it away from the (now) more Premier League-focused MOTD name. Which means that, in this age of iPlayer and rights issues, the two sets of highlights are now kept in separate containers. Even when they’re next to each other in the schedule.

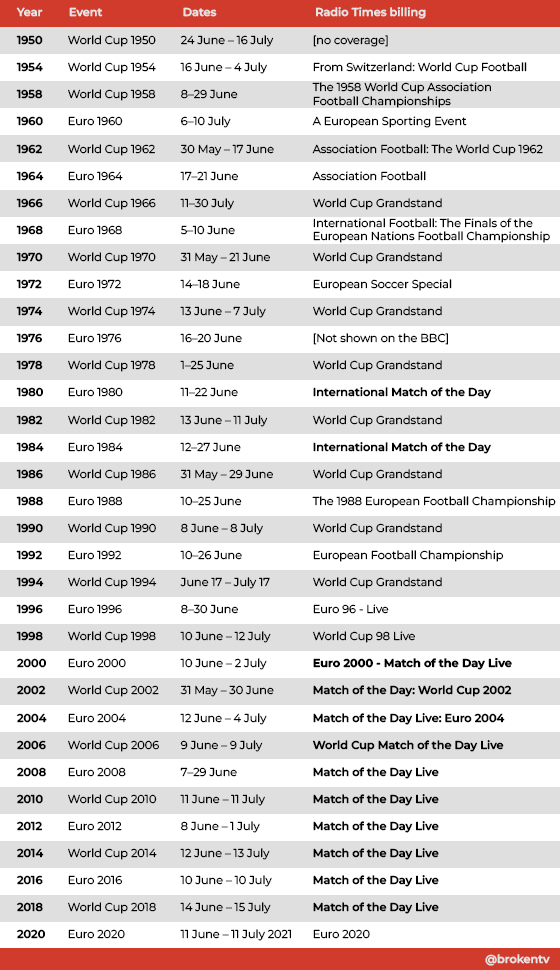

How much better would this be if it had involved Gary Lineker walking across the studio floor to a different desk at 11pm? Like Stephen Fry walking away from the DEF II desk to wheel in the Babylon 2 set in the first ever edition of DEF II? The title World Cup Match of the Day was used when nightly highlights round-ups were broadcast in 1974 (live matches then going out as World Cup Grandstand). Then that title lay dormant for 15 years, with the programme title reused for highlights of Italia ’90 qualifiers in 1989, provided they were on a Saturday – midweek qualifier highlights went out as part of Sportsnight. That is until October 1989, when World Cup Match of the Day was used for a live (midweek) broadcast of the Poland v England qualifier. Then, the programme title hibernated until the 2006 World Cup in Germany, except for the highlights packages for Euro 2000 that used “MotD at Euro 2000” but not for the live matches… look, here’s a table of RT billing titles for every major international football tournament since 1950. Titles included in MotD’s episode count are in bold.

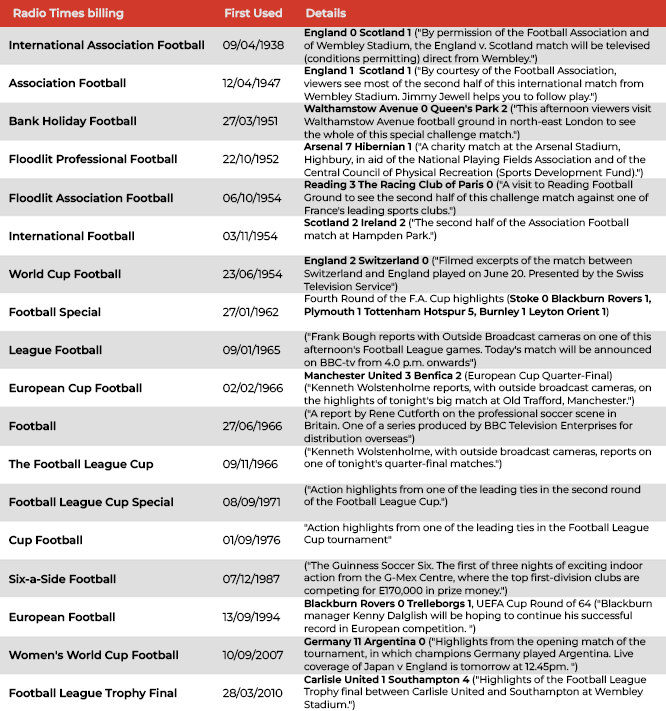

Yes, “A European Sporting Event” for the 1960 final. Very grandiose. Anyway, let’s rewind a bit. Football on the BBC has gone out under a variety of guises – hey, here’s another largely pointless table, this time of non-MotD football match billings in the Radio Times:

The entry for ‘Football’ up there is a bit tenuous, admittedly. The next time just ‘Football’ was used as a programme billing was in 1984, for coverage of the The Courage Soccer Six from Birmingham, so mentally insert that in place if you prefer. So, it’s probably for the best that they settled on another programme title. The above isn’t even a comprehensive list – between 1971 and 1997, the Sportsnight Special branding was used for midweek football matches, mostly but not exclusively for those broadcast live (first: FA Cup Third Round Replay highlights, last: live coverage of AS Monaco v Newcastle United in the UEFA Cup).

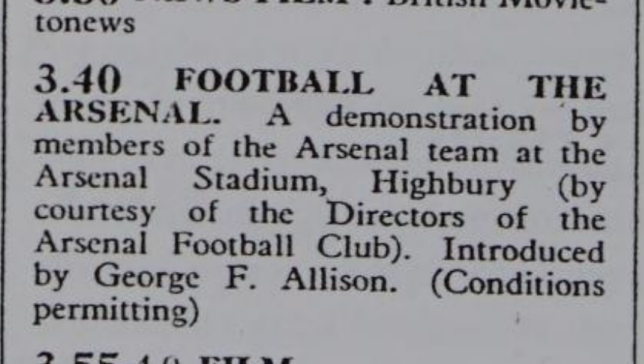

The BBC’s first televised association with Association (Football) dates all the way back to September 1937. That inaugural coverage was, as you may well already be aware, a thrilling tussle between Arsenal and… Arsenal Reserves at Highbury. Yep, fifteen minutes of a training match. While this could easily have been some filmed footage flung out as part of Newsreel, the BBC didn’t take that easier option. The Beeb’s brand new mobile television unit travelled to Highbury to broadcast the footage live. The first ever billed football match (as shown below) was indeed “a demonstration by the members of the Arsenal team” on 16 September 1937, but live footage of football first went out a day earlier – two minutes of soundless but live footage of the Arsenal team went out at 3.45pm the previous day, as part of magazine series Picture Page.

Such was the cost of sending the mobile television unit (around £35, or the price of a pie at Wembley in 2023), a series of broadcasts from the ground were requested to make the whole affair a little more cost effective. As a result, a total of three transmissions were made from the ground, plus (following that brief initial broadcast on Picture Page) a test transmission of Arsenal Reserves versus Millwall Reserves was beamed back to a special viewing room at Ally Pally, so BBC bosses could gauge how suitable this football lark was for public consumption.

The second billed visit to The Arsenal occurred on 17 September that year, which led to another broadcasting first: George Male becoming the first footballer ever to be interviewed on live television. On being questioned about the diversity within the Highbury playing staff, Male proudly proclaimed “they are from Scotland, Yorkshire, Wales, all over the place… provided they are British subjects. We couldn’t put a foreigner in the team”. Plus ca change, eh? As a result (of the broadcast, not Male’s xenophobia), the BBC would go on to broadcast the FA Cup Final between Preston North End and Huddersfield in 1938, followed a year later with the Portsmouth versus Wolves final – the latter listed alongside the caveat “unless anything untoward happens” in the Radio Times (and a warning that “no rediffusion in places of public entertainment will be permitted”).

Following the war, the BBC were keen to show more live football for the demobbed masses, but there was a problem. The Football League – gatekeepers for the bulk of English professional matches – were dead against the idea, calculating that allowing the still-small television audience to watch coverage on tiny monochrome sets would be preferred to the full-3D, full-colour, full-Bovril matchday experience, and stop attending matches in person. Luckily for the BBC, the FA in general were more receptive to the broadcaster. Less luckily for the BBC, technology at the time limited them to covering events within a 20-mile radius of Alexander Palace.

As a result, the next televised football match, taking place on Saturday 19 October 1946, was from the lofty heights of the Athenian Football League, with Amateur Cup holders Barnet entertaining Wealdstone. Even then, the broadcast was far from simple – the permission of a local resident had to be sought so BBC engineers could borrow their phone line, and from another resident to plonk some scaffolding for cameras on their allotment. Thus the programme budget was duly increased to include compensation for damaged crops.

That wasn’t the end of the technical hitches. Despite the promise of “part of the first half and the whole of the second half” in the Radio Times, bad light ultimately curtailed the live broadcast fifteen minutes from the end of the match.

At least anyone watching from those houses in the background could just have looked out of their window. Despite those obstacles, the broadcast was deemed a success, and the BBC would go on to broadcast further (non-Football League) matches from the London area.

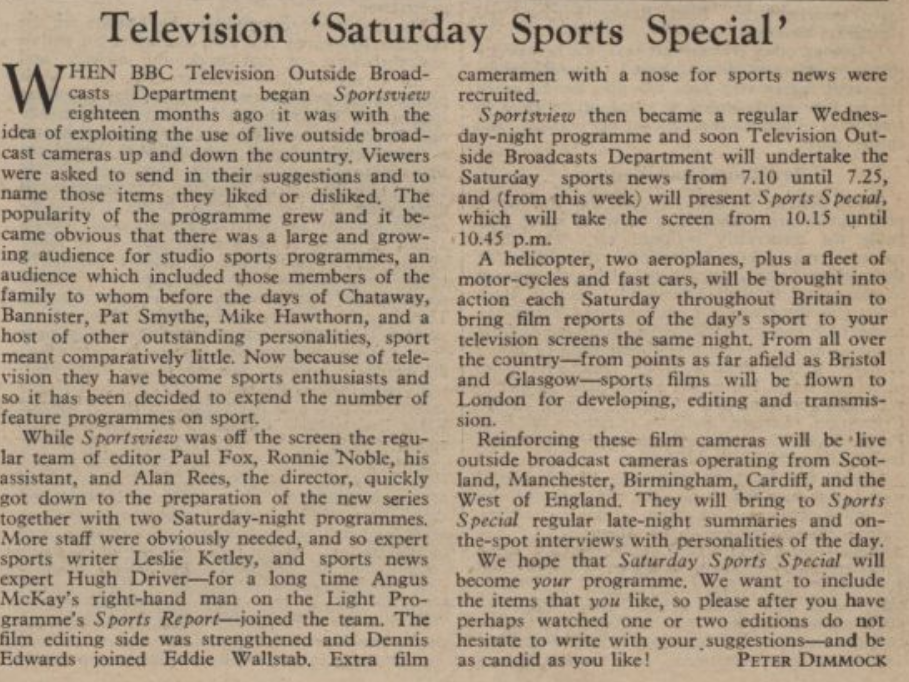

By 1954, the popularity of television had grown, along with the demand for televised sport. As a result, Head of Sport Peter Dimmock along with Paul Fox devised Sportsview, the BBC’s first midweek sporting magazine programme. This offered football match highlights alongside other sports, and soon became must-see viewing for sport fans lucky enough to own a television receiver. That popularity led to Sports Special, a Saturday night spin-off for the series packing a more football-focused remit, with Peter Dimmock taking to the Radio Times to provide exciting details on how “a helicopter, two aeroplanes, plus a fleet of motor-cycles and fast cars” would be employed to rush filmed reports from stadia to studio each week.

Radio Times Issue 1660, 4 Sep 1955 – 10 Sep 1955 Sports Special would go on to run for ten years from 1955, accompanied in October 1958 by Saturday afternoon stablemate Grandstand. However, the very march of progress that made the programme possible in the first place (including, of course, the thrilling assistance of fast cars and helicopters and possibly at least one Milk Tray Man) would lead to its downfall. Match reports being shot on 16mm film meant that on arrival at the studio, footage first had to be processed, returned as wet negatives and frantically edited at Lime Grove by harried editors praying that they’d get the job done in time for transmission. The reliance on filmed reports (and the budget only allowing for a single camera at each match) also carried the risk of a crucial goal being slammed home while the camera operator was changing reels.

Videotape and multi-camera coverage were still only on the horizon, but Sports Special’s days were numbered. What was once a regular weekly treat became a more sporadic offering, and despite rebranding for most weeks as Football Special from late 1961, in April 1965 the programme would air as a Saturday night strand for the last time, by now on the rechristened BBC-1, with a broadcast of that day’s England v Scotland match from Wembley.

But! Hope for football fans was not lost. Over on upstart BBC-2, a new programme had arrived in 1964, opening with the classic Wolstenholme words “Welcome to Match of the Day, the first of a weekly series coming to you every Saturday on BBC-2. As you can hear, we’re in Beatleville for this Liverpool versus Arsenal match”, and ending with a score of 3-2 to the Mighty Reds.

It would go on to become quite popular.

The write-up for that first-ever episode in the Radio Times went as follows:

Today for the first time soccer fans can watch a feature-length version – as opposed to a potted ‘highlights’ version — of a regular League fixture. Which one? That, by agreement with the Football League, remains a secret until 4.0 this afternoon. But Bryan Cowgill, BBC-tv’s sports chief, promises that it will be a top match.

The agreement by which BBC-tv won permission for this came after careful negotiations between Bryan Cowgill and League Secretary Alan Hardaker. It allows for fifty-five minutes of coverage, enough to show the whole development of the game, and for its screening at a more popular hour.

Up to now we have only been able to show ten-minute edited films of any given match. which, effectively meant a machine-gun succession of goal-goal-goal,’ says Cowgill. ‘Now we can fall in line With BBC-2’s policy by offering “depth” treatment of our most popular sport’. To those who think this breakthrough is a further blow to turnstile takings, he offers his experienced opinion that ‘television never kept anyone away from the best in sport.’

In charge of the new venture as producer is Alan Chivers, BBC-tv’s most experienced soccer specialist. He intends to make full use of the technical advantages of 625 lines, and says: ‘We’re no longer restricted mainly to the close-up, With 625’s greater definition we can use wider shots without losing clarity, and so show much more of the overall pattern of a game.’

Radio Times Issue 2128, 20-26 August 1964

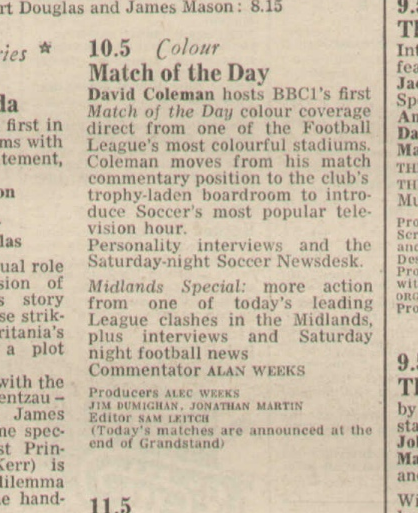

Following the 1966 World Cup, famously won by A British Team Wearing Red (haven’t checked, I presume it was Wales), MOTD made the move from BBC-2 to BBC-1 for the 1966/67 season. Although the programme would move back to BBC-2 for a week in November 1968 so that the first colour edition of the series could be shown. Any football fanatics without a 625-line set that week at least got to watch Hitchcock’s Anatomy of a Murder on BBC1 that night. It wouldn’t be until 15 November 1969 that colour MOTD first arrived on BBC-1 – on the channel’s first official day of colour TV.

If you’re wondering, the first colour programme in the listings for that day: The Weather. Transition to colour TV aside, the core remit of the series – football highlights on a Saturday night – remained unchanged for a long time. Even when events called for a special episode of MOTD, it was usually affixed to standard match highlights, as had been the case on 10 Jan 1970 and the excitingly-billed “Match of the Day Special: 1970 World Cup Draw“. This contained the exciting curveball of having David Coleman reporting from Mexico City’s Maria Isabella Hotel, where the 16 qualifying nations discovered who they’d be playing that summer (“Presented by Telesistema Mexicano”, no less). Even then, as befitting the programme, the bulk of the content that week was still of match highlights from a suitably sodden football ground.

A year before that Mexican jamboree, MOTD had added the first ever slow-motion replays to their coverage, an innovation that would make a huge difference to the way football was covered. And those innovations were increasingly important. At a time when the USA and USSR were in a PR war to get the first boots on the moon, BBC and ITV’s respective football flagships were locked in a similar, if slightly less cosmic, battle.

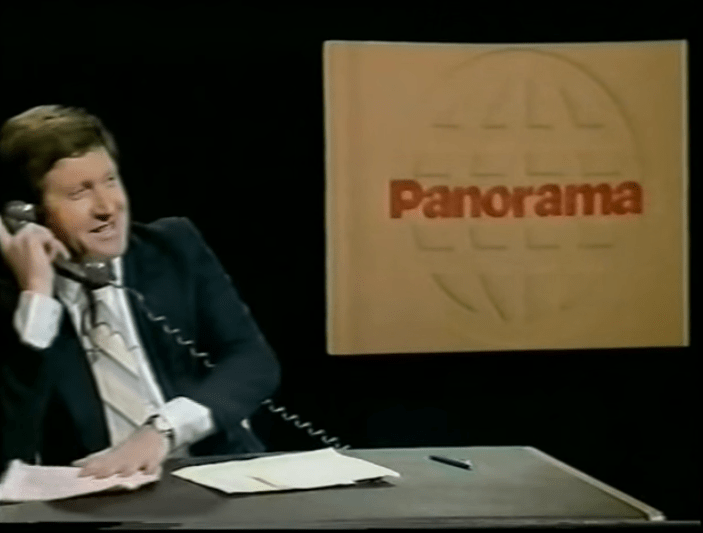

The nature of ITV meant there was no network-wide football highlights programme – the whole story of football on ITV could fill an entry on its own – but the big hitter was undoubtedly LWT’s The Big Match, which tried to add a little Light Entertainment pizazz to the whole affair (oh, okay. Brian Moore and a desk with a phone on it). The battle ultimately became so intense that Michael Grade led a coup to snaffle up exclusive rights to the Football League in 1978, the move was famously reported in the papes as ‘Snatch of the Day‘. Which would have been quite witty had the pun not already been public knowledge since a 1974 anti-pickpocket public information film. Luckily, the Office of Fair Trading put a stop to that nonsense, and Match of the Day was safe. For a while.

The battle of the broadcasters intensified throughout the next few years, though there was a truce of sorts after the channels agreed to alternate ownership of the prime Saturday night highlights slot, meaning MOTD aired on Sunday afternoons throughout the 1980/81 and 1982/83 seasons. However, for 1983/84 there was a new, long-awaited change for both channels: live coverage of Football League matches. It’s almost strange to imagine such a thing at a time when almost every single match in the top five tiers of English football can (legally) be watched live, but that represented the first time live league football would be shown on TV since 1960. Highlights briefly faded into the background. Especially during the start of the 1985/86 season, when disputes over money meant TV was a football-free zone for several months. At least that led to Saint & Greavsie parading West Ham’s leading goalscorer Frank McAvennie around London to see if anyone would recognise him, which is quite fun.

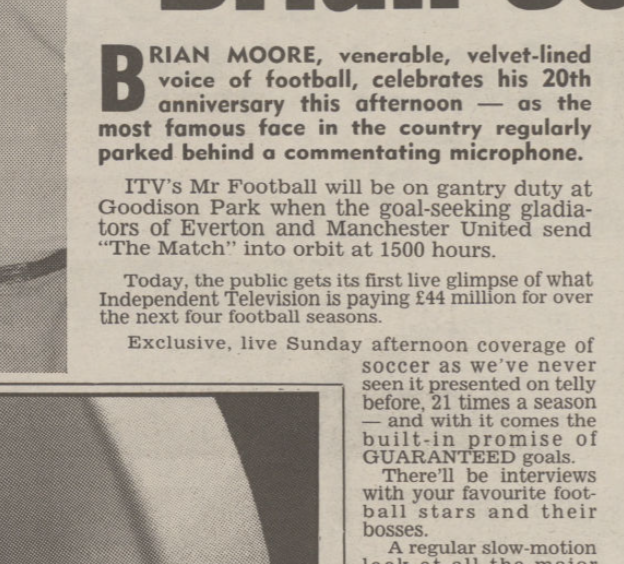

1988 saw a dramatic change to coverage for the Beeb, with ITV paying a (then-)whopping fee for exclusivity. It certainly seems quaint now, but paying £44m for 21 live matches per season was big news at the time, not least as it restricted MOTD to coverage of the FA Cup (and for the most part, a rebranding to Match of the Day: The Road to Wembley).

As football’s post-1990 popularity soared Skywards (insert a Waddle penalty gag here if you must) even bigger changes were afoot. But then you probably already know all about that. At least that meant top division highlights returned to the BBC.

And – if we all pretend those few years of Andy Townsend’s Tactics Truck et al were just a national hallucination – that’s where they’ve stayed ever since. And indeed, the lockdown-era Project Restart even led to the return of Live Top Tier Football to BBC1 after a gap of 32 years.

The mission statement of the programme has certainly changed a lot since Kenneth Wolstenholme’s original trip to Beatleville. The very thing original producer Bryan Cowgill was so happy to be leaving behind – “ten-minute edited films of any given match” – is now the core product of the programme. But, in a world where watching live football on TV is largely restricted to those with a disposable incomes or an illicit IPTV hookup, it’s still appointment television for many, and for everyone else it’s just nice to know it’s still there.

After all, we’ve now seen a vision of the future without Match of the Day. It wasn’t pretty.

NOTE: If you’d like to read a lot more about the history of football on British TV, be sure to take in Steve Williams’ superb Goalmouths over on OffTheTelly.

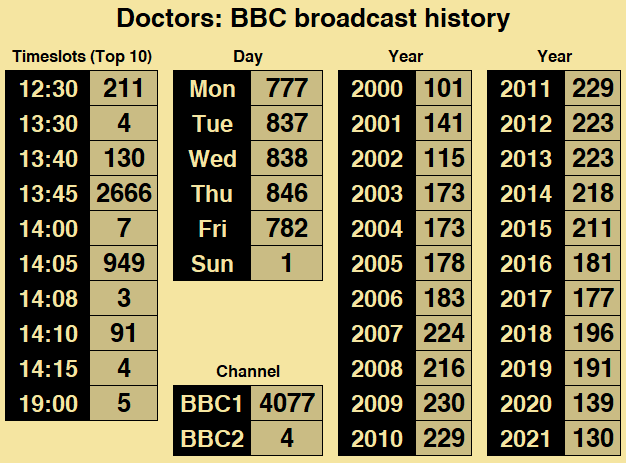

15: Doctors

(Shown 4081 times, 2000-2021)

For a genre of television that has seemed utterly omnipresent since the days of Stooky Bill, it’s actually a little surprising to learn that medical drama series were few and far between in the early days of British television. In the early days of the BBC Television Service, the closest you were likely to get was seeing a concert by someone who’d left the medical profession for the world of music, such as pianist Leslie ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson (5 Dec 1936, Starlight) or Norman Hackforth (4 Feb 1937, The Composer at the Piano).

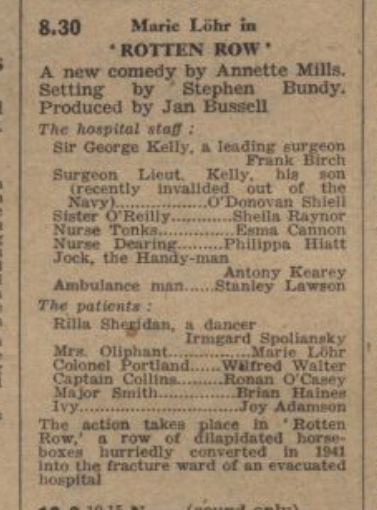

As was the style at the time, there would occasionally be serious factual programming based on medical matters, especially in the post-war years, such as 1947’s I Want to be a Doctor, but dramatic fiction from within doctorly settings were a feature that television simply didn’t seem to fancy. It’s tempting to suggest that the medical profession was deemed sacrosanct when it to TV’s myopic gaze, but that’s swiftly disproved by there being a smattering of comedy plays about the profession. May 1947 saw Annette Mills’ comedy feature Rotten Row, where a dilapidated row of horse boxes is converted into a fracture unit next to an evacuated hospital in post-war London (I repeat: a comedy), while August that year saw the screening of The Amazing Dr Clitterhouse, a comedy thriller by Barre Lyndon.

See, it wasn’t just me having a fever dream. By the late 1940s Britain finally had a National Health Service, so it’s perhaps understandable that television preferred to spend airtime demystifying what went on behind hospital doors. As a result, factual programmes often made an appearance in the Radio Times, such as 1948’s Mass Radiography, (“The Medical Officer in charge of a Mobile X-Ray Unit belonging to the North-West London Regional Hospital Board demonstrates a new technique of diagnosing chest diseases in their-early stages”), or 1949’s medical documentary series Matters of Life and Death (“Episode 7: Dr. F. Avery Jones and Mr. Norman Tanner, a physician and surgeon who have made a special study of gastric and duodenal ulcers, discuss their prevalence and show how they are diagnosed and treated”). All very worthwhile, but hardly using matters medical to offer a sense of escapism for the TV audience.

That changed in 1951, with a six-part television adaptation of Anthony Trollope’s 1855 book The Warden. The first of the Chronicles of Barsetshire series, the book followed the fortunes of Mr Septimus Harding, an elderly warden from Barsetshire-based Hiram’s Hospital. That offering aside, it took the launch of ITV in 1955 to successfully transplant the notion of a medical TV drama into Britain’s cathode-ray tubes. Emergency Ward 10 (ATV, 1957-67) became one of the nascent network’s breakout hits, albeit one that came about due to a misunderstanding. It had been suggested to programme creator Tessa Diamond that a show about daily hospital life might be a hit. It was only after Ward 10 was created that her agent revealed the original suggestion was actually for a documentary series.

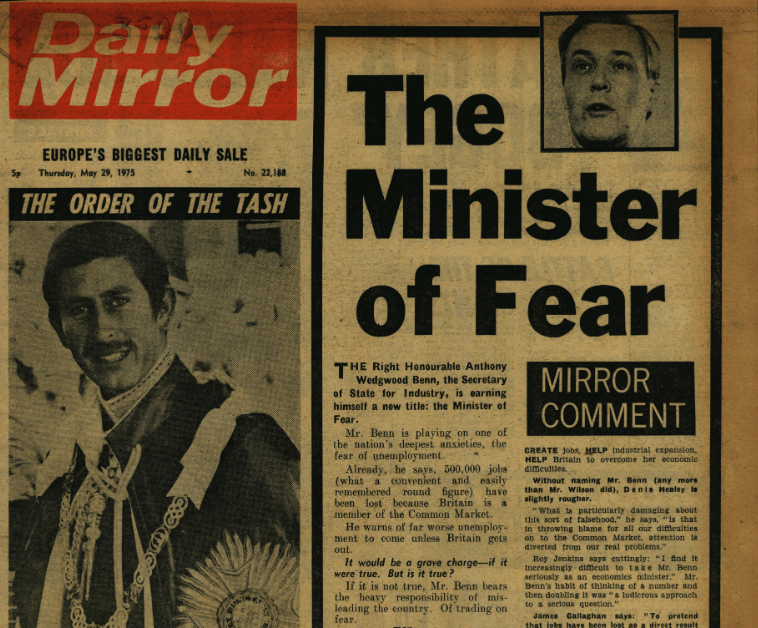

Daily Mirror, Tuesday, Feb. 19, 1957 Once that happy accident was out of the way, the programme quickly became a success. So much so, in ten years on the air it clocked up a total of 1,016 episodes – including in 1964 one that featured an early example of an inter-racial kiss between two actors.

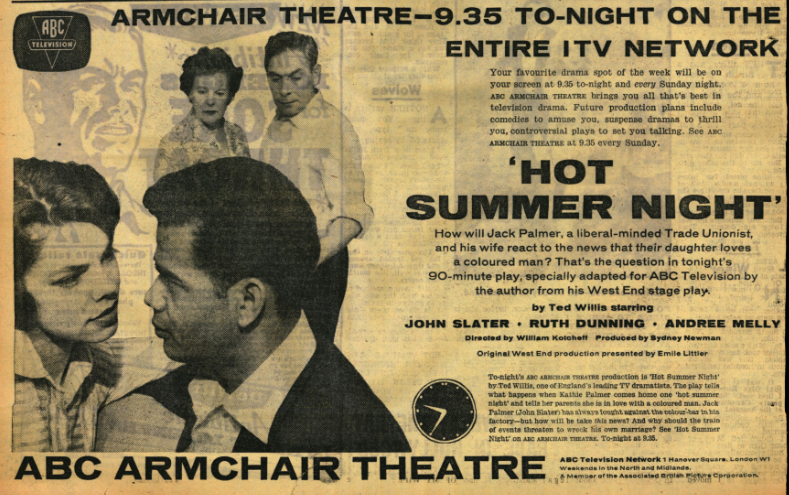

Aside: For a spell, it seems to have been considered television’s first-ever such embrace (coming a full four years before the Star Trek episode “Plato’s Stepchildren”). However, it was actually preceded by both Granada’s 1962 Play of the Week In Your Small Corner, and 1959 ABC Armchair Theatre play Hot Summer Night – both plays featuring Jamaican actor Lloyd Reckord.

An inter-racial relationship being portrayed in a 1959 TV drama? Very progressive. Only billing the three white actors in the newspaper adverts for it? Not so much. Anyway, with Ward 10 proving a success, other medical soap operas would later appear in an attempt to rebottle that magic, such as General Hospital (ATV, 1972-79), Angels (BBC, 1975-83) and Children’s Ward (Children’s ITV, 1989-2000). On top of that, daytime TV found plenty of room for antipodean imports The Young Doctors (Nine Network 1976–1983, airing on ITV from 1982 and Sky Channel from 1989), A Country Practice (Seven, 1981–1994, shown on ITV from 1982 and Sky Channel – in primetime! – from 1984) and Shortland Street (TVNZ 2, 1992–, shown on ITV from 1993).

For those of a certain age, the above image will be closely associated with being off sick from school. As the millennium (and to a lesser extent, the Willennium) neared, the previously-listed Holby City (BBC, 1999-2022) started a residency on BBC1. And, with that proving popular enough for BBC bosses to attempt a daytime version, this was followed a year later by the first episode of… Doctors. Yes, we’ve got to it at last. Phew.

Set in the fictional Midlands town of Letherbridge, the Chris Murray-devised programme follows events within the local doctor’s surgery and the nearby university campus surgery, along with those of the stakeholders within.

Commissioning a brand-new scripted drama to go out in the pre-news slot 12.30pm each weekday – a place you’d usually expect to contain an episode of Changing Rooms, Celebrity Ready Steady Cook or Bargain Hunt – was certainly a brave move by BBC head of daytime programming Jane Lush. To remain receptive to occasional viewers, the programme was to use self-contained stories featuring the key cast rather than having long-running plot strands (a la imperial phase The Bill). In addition, casting cosy drama series stalwart Christopher Timothy as key character Mac McGuire certainly wasn’t going to hurt.

To introduce viewers to the series, the opening episode aired in a primetime-adjacent slot of 6:35pm on Sunday 26 March 2000, with the first regular daytime episode airing the following lunchtime. Under the auspices of showrunner Mal Young, whose vintage included Holby City, Casualty and would later cross the Atlantic to exec produce The Young and the Restless, Doctors proved successful enough to be tried out in a 7pm weekday slot in the summer of 2000. However, it quickly became obvious that a rival soap wasn’t much of a threat to the Emmerdale behemoth, and it returned to the cosier confines of 12.30pm.

And that happy little niche was where it would stay for just over a year and a half, before shifting to a 2.10pm slot in November 2001 in a soapy double-bill with Neighbours. And that was where it stays for several years, Letherbridge being happily twinned with Erinsborough five days per week, making it a Doctors appointment you weren’t likely to miss (oh shut up).

However, in 2007 calamity struck. With the FremantleMedia demanding a whopping £300m from the BBC in return for the rights to Neighbours for the next eight years, the flagship show was instead set to move to Channel Five. The result: a major soap-shaped hole in BBC1’s daytime schedule. What was the BBC to do? Splurge a chunk of programme budget on nabbing the rights to Shortland Street? Fling on repeats of The Sullivans? Nope, by that point Doctors was doing well enough for it to be promoted into that key post-news slot, with the remaining episodes of Neighbours switching to its post-2pm slot.

Doctors continued to perform admirably for the lunchtime audience, but finding a companion for it proved a little more tricky. US drama show Monk was tried out in that slot during December 2007, before long the Neighbours burn-off episodes were restored to the slot while packing its bags and preparing for life on Five. Diagnosis Murder was given a run in that slot a few months later, but April 2008 saw the launch of the BBC’s new secret weapon: Out of the Blue. It was cool. It was sexy. It could air five days per week. And most importantly, it was Australian.

Set in the fashionable Sydney beach suburb of Manly, the action started with a group of thirty-year-old friends returning home for a high school reunion, only for the reunion to end in murder and an investigation into which of them done it. It couldn’t fail. And crucially, it had actually been commissioned by the BBC, so could be tailored to meet the needs and wants of a British audience.

Obviously, it failed. Big time. Ratings were so unspectacular, it was nudged over to BBC2 after just fourteen episodes on BBC1, and lasted less than a year before being cancelled entirely. Not to worry though, Five picked up the repeat rights to the series, and put them out on digital offshoot Fiver. I’m assuming for a much lesser outlay than they’d paid for Neighbours. Diagnosis Murder picked up the post-Doctors reins, and proved a much more popular companion. After all, it is the 62nd most-broadcast programme on the BBC of all time.

Speaking of Doctors (which is what we’re supposed to be doing here, of course), it was the bedrock of the BBC daytime schedule. By 2010, it was picking up a comfortable two million viewers per episode, regularly winning the daytime ratings war. Indeed, some episodes even rated as high as 3.5 million viewers, numbers that EastEnders producers would probably throttle Wellard for nowadays.

And as time went on, those viewing figures only continued to grow. By 2017, they were sitting at a comfortable 2.5 million per episode, at one point reaching a peak of four million (according to a Telegraph link I’m not going to pay to read, so we’ll take Google’s word for it).

Now, as will be abundantly clear from this update, I’ve barely ever watched an episode of Doctors. However, what has become clear to me is that the creative team behind it aren’t afraid not to try something thrillingly different from time to time. The most obvious example of this would be superbly titled episode “The Joe Pasquale Problem“, which involved a patient seeing everyone as Joe Pasquale (special guest for that episode: Joe Pasq… oh, you’ve guessed).

Better still, an episode airing on the telltale date of 31 October 2014 saw character Al “forced to confront his scepticism of the supernatural when he finds a whistle with mysterious powers”. Or, if you prefer, an episode of a daytime soap opera was used as an excuse to put on a production of M R James’ 1904 ghost story Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad. You don’t get that with Emmerdale, do you?

That’s the only episode of Doctors I’ve ever watched, and not going to lie – it was great. The modest budget of a soap episode really helped it capture at least a soupçon of the 1970s aesthetic of the original A Ghost Story for Christmas, which is handy as Jonathan Miller’s 1968 version of the same was a decidedly different beast from the annual anthologies it begat. That Doctors episode is on DailyMotion if you fancy seeing it. And so are plenty more, if you like the sound of the series and would like to catch up.

(By the time you finish that, I might have the next entry on the list written.)

That’s another one in the bag, which isn’t a literal bag. More ‘soon’, if I get out the habit of spending an hour researching something for the sake of a single sentence about something not really connected to the programme I’m meant to be talking about.

-

Silenza: Ne Televisione (The 100 Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes Of All Time, 18 and 17)

On with this list!

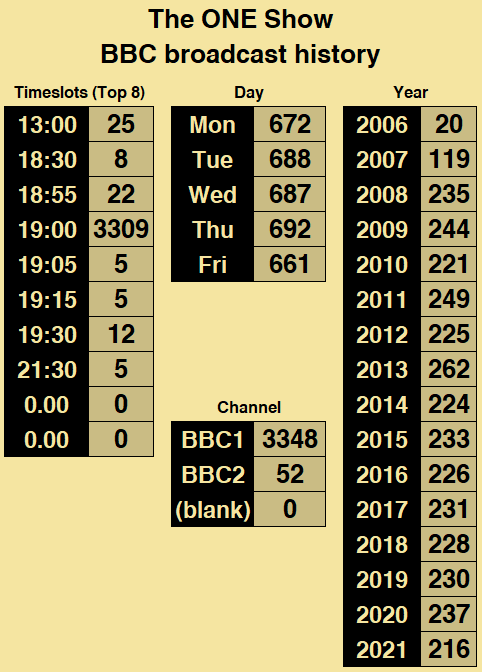

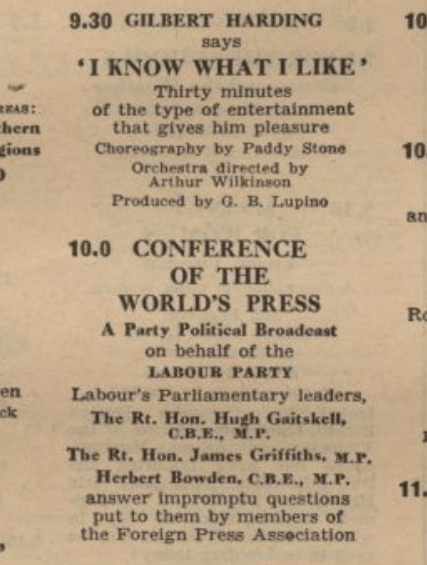

18: The ONE Show

(Shown 3400 times, 2006-2021)

Apparently, ‘ONE’ is capitalised, despite the title being all lower-case in the title sequence. What’s the deal with that?

There are some TV reboots that will never, ever be a success until – against all reasonable logic – they just are. When the BBC initially announced their big new Saturday night Light Entertainment extravaganza was going to be a reboot of sleepy old Come Dancing, many scoffed. And with good cause. Throwing a few newsreaders or athletes into a fusty old format like that wouldn’t be a success! Oh. It was. A huge success.

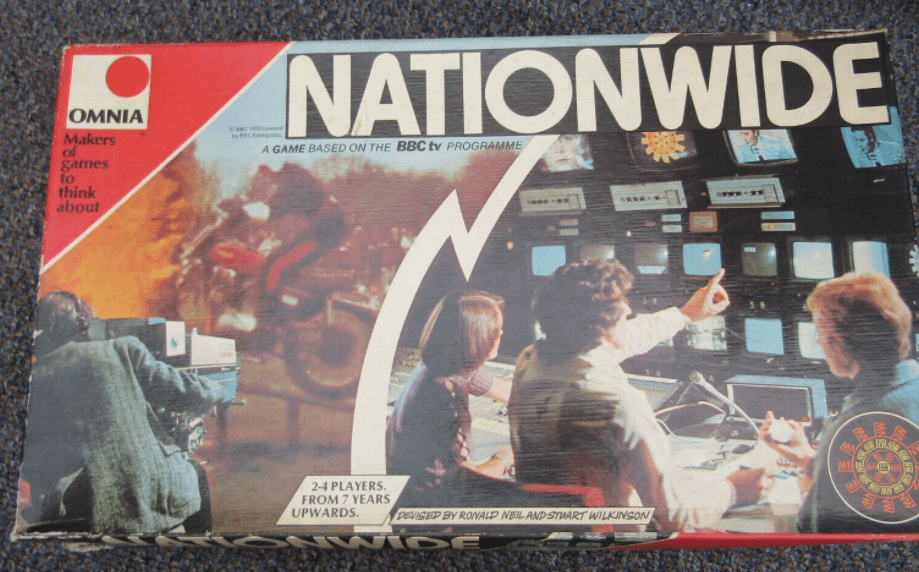

Similarly, when the announcement was made that the BBC were going to blow the dust off Nationwide, plonk Someone Off EastEnders and A Man Off The Football onto the presenting couch and spend four weeks in 2006 waiting to see if anyone would tune in, the reaction was similar. It was even airing at the distinctly 1976 time of 6.55pm each weekday (seemingly done so anchors of the preceding regional news bulletin could throw straight to it). It wasn’t the 1970s any more, you idiots! We’ve all got Motorola RAZR phones now, and now knows that other space-age things are just over the horizon? This is the future!

The Future (2006 Edition). Luckily for the BBC, the bigwigs weren’t listening to idiots like, erm, me. It didn’t hurt that that particular Man Off The Football happened to be Adrian Chiles, whose TV stock was high off the back of Match of the Day 2 and the BBC’s World Cup coverage a couple of years earlier, his particular brand of black country bravura proving a hit with viewers. His initial co-host, actor, presenter and founding Loose Woman Nadia Sawalha was seen as a similarly safe pair of hands. But surely the TV landscape had moved on from such a format?

There was a sense of neatness to what BBC One were doing. ITV had a nicely stripped and stranded schedule each evening – Local and National news from 6pm, Emmerdale at 7pm, and (for three nights each week at the time) Corrie at 7.30pm. In contrast, BBC One had a much more mixed bag at 7pm each evening. Aside from The ONE Show in 2006, there had been 26 different programmes airing on weeknights at or around 7pm – some solid (Question of Sport, Watchdog), some less so (Davina McCall’s short-lived chat show, Davina). Having something settled in that slot would be more likely to attract a loyal audience who, it was hoped, might just stick with BBC One for the evening.

Of the available options, a magazine show made the most sense. There was no way the Beeb were going to try another soap in that slot (cost aside, the spectre of Eldorado still haunted the BBC boardroom), the flop that was Davina suggested a Wogan-style chat show wasn’t the safe option it once was, and game shows were for earlier in the evening. Nationwide reboot everyone? Nationwide reboot. It couldn’t fail.

Even with a title sequence and theme that seem all kinds of wrong to modern eyes. And ears. Still, that answers the question about why ONE is in all caps. No, seriously – it couldn’t fail. In the initial four-week run, critics were not kind. “We can look forward to a future without this patronising pile of TV excrement” quipped the Mirror’s Kevin O’Sullivan, while former Nationwide producer David Hanington wrote to the Guardian to dismiss the programme as “a load of predictable, pedestrian tat”. However, the ratings were solid enough, usually between three and four million per night, though it was another factor that ensured The ONE Show would return.

The programme had been the brainchild of BBC One controller Peter Fincham, who’d only recently been responsible for another 7pm disaster (the aforementioned Davina). Throwing a bunch of time and money a second failed spoiler for Emmerdale would make for some pretty bad optics. And so The ONE Show would return a year later, with a full run beginning in July 2007.

And it would no longer look like it’s being beamed straight from a retail park. Now it was back for a long haul, scales of economy meant production values could be boosted, and the programme was relocated from regional-content-ticking Birmingham to where-the-stars-are London. Breakout ‘star’ of the programme Adrian Chiles became focal point of the series, with Myleene Klass replacing Nadia Sawalha alongside him. From there, the series became the TV fixture we’d all know and sometimes maybe even watch (if it’s only one of the new rubbish Simpsons episodes on Sky One).

There have been bumps along the way. Some of them were especially rocky, like Hardeep Singh Kohli and Carol Thatcher each being dismissed from the show for acts of arseholery, for example. Some were a little more easier for the ONE Show axis to withstand. For example, after a few months on the chair, Klass left on maternity leave, and in came new co-host Christine Bleakley (later Lampard). The on-screen chemistry between Bleakley and Chiles was a winner, and the programme grew in popularity. Somewhere, in ITV’s gothic castle looming over the South Bank, an underling was frantically taking notes.

Another suspension-crunching bump came along in 2010, with the announcement that Friday episodes would be boosted to a full hour… but that those episodes would use Chris Evans as host. Yet another doomed attempt to cram that mid-90s TFI Friday magic into the wrong TV bottle, and which only turned Adrian Chiles against the show, subsequently announcing his departure. In came a new host, 8 Out Of 10 Cats team captain Jason Manford. By the time Manford’s tenure began, Bleakley also departed, in order to team up with Chiles on ITV’s rebooted breakfast show Daybreak (spoiler: it didn’t work out well). In her place came S4C’s Alex Jones, who was set to be the show’s sole five-day host – Manford appearing on Monday to Thursday, and Evans each Friday. All nicely settled now. Good.

For a few months, anyway.

Come November, a tabloid scandal did for Jason Manford’s stint on the series, and in came a series of guest presenters, including Alexander Armstrong, Matt Allwright and Matt “Prime Minister, How Do You Sleep At Night?” Baker. The following year, Matt Baker was appointed perma-host, albeit with guest presenters taking the hotseat each Friday following the departure of Evans.

Let’s not forget this golden moment, either. From that point, things have been a bit more settled for the series. Matt Baker departed (for sensible non-scandal reasons) in December 2019, with more guest hosts initially filling in alongside Alex Jones. April 2021 saw Ronan Keating and ex-England ace Jermaine Jenas appointed as regular co-presenters, where they remain to this very day. With Lauren Laverne also now part of the regular host line-up, the ONE Show, erm, shows no sign of stopping any time soon.

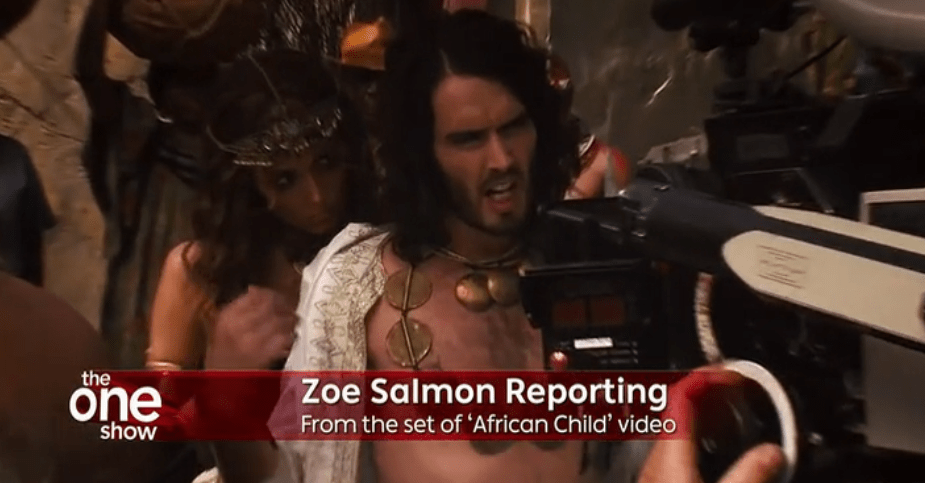

Indeed, The ONE Show even once appeared in cinemas around the world. Well, sort of. The opening scenes of 2010 Jonah Hill/Russell Brand offering Get Him To The Greek included the familiar ONE Show opening titles to the programme as part of on on-location interview with Brand’s wayward rocker Aldous Snow. Might not sound like much, but it’s pretty much the most interesting thing about that film.

Tied in first place with the “I’m not saying I’m Jesus, that’s for others to say” joke stolen from Richard Herring, in fact. You only need to watch the first five minutes of this film, basically. [UPDATE 8pm 06/06/23: With thanks to George Stevens for asking on Twitter about two episodes showing as broadcast on a Saturday and Sunday, I’ve now corrected the episode count. One had been a mislabelled episode of daytime spin-off The One Show: Best of Britain airing on a Sunday, one had been some rogue data that had crept into my database. Fixed ep count above, and fixed table below.]

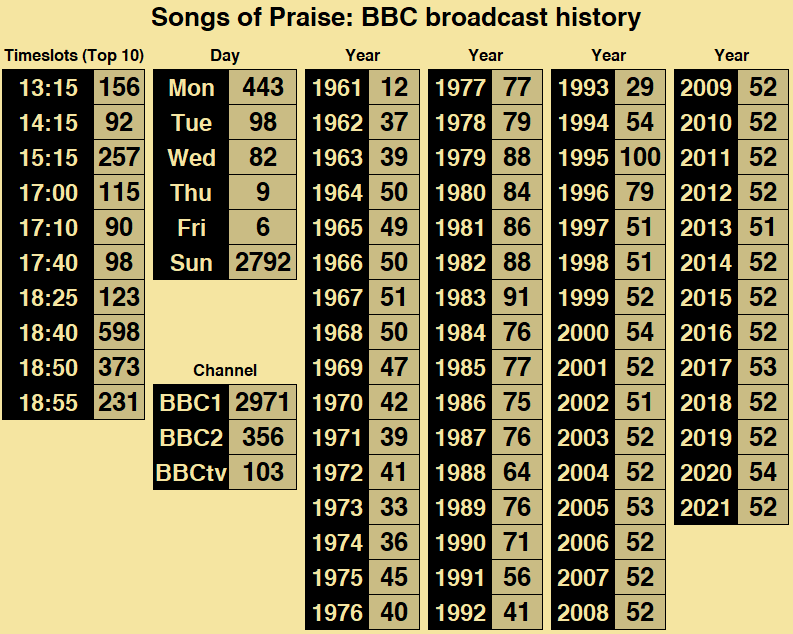

17: Songs of Praise

(Shown 3429 times, 1961-2021)

There aren’t too many British television institutions that started being broadcast solely to Wales. SuperTed, Fireman Sam, the few months in 1994 where BBC2 broadcast Pobol Y Cwm in an afternoon slot (we all remember the Radio Times’ boast that “the Deri Arms could become as famous as the Vic and the Woolpack”). Admittedly, quite a drop-off between those last two*.

(*Side point: there’s such a paucity of British sketch comedy on TV these days, were it still a category in the British Comedy Awards, S4C preschool sketchcom Cacamwnci would win a nomination by default.)

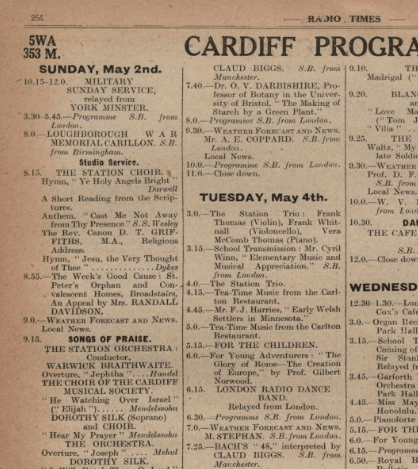

And yet, the Land of Song is the place closely tied to the (eventual) rise of religious programming on British television. Indeed, the title Songs of Praise dates back as far as 96 years into the past thanks to early BBC radio service 5WA Cardiff. Songs of Praise 1.0 first appeared on 2 May 1926 and featured The Station Orchestra (conducted by Warwick Braithwaite), The Choir of the Cardiff Musical Society and soprano Dorothy Silk.

Decades later, a format not dissimilar to Songs of Praise would appear on the nascent BBC Wales television service, going out under the name Dechrau Canu, Dechrau Canmol (“Start Singing, Start Praising”) from New Year’s Day 1961, with a half-hour of community hymn singing from Swansea.

However, there’s a bit of a journey between those two points.

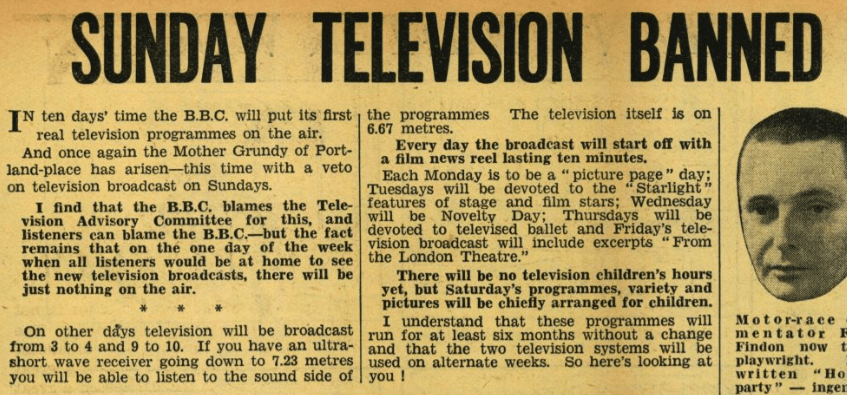

It took a long time to get there, in part thanks to the very concept of television on a Sunday having been initially forbidden by the Television Advisory Committee way back in 1936.

Daily Mirror, Fri 23 Oct 1936. The blanket ban wasn’t to last for long, however. As the Daily Mirror pointed out in the run-up to the launch of regular BBC-tv programming, it was a bit much that anyone who’d worked hard all week to pay for a television set wouldn’t be able to watch the blessed thing on their day of rest. And so, from 1938, Sunday broadcasting trickled onto the Television Service for the first time. That said, the hours were strictly rationed, so as not to tempt churchgoers away from Sunday services.

As far as I can find, Sunday programming on the Television Service back then was surprisingly secular, with everything from puppetry to classical music in place, but save for the occasional teleplay with a religious-sounding name (such as James Bridle’s Tobias and the Angel, or George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan) television seemed very wary of muscling in on the territory of organised religion.

For the most part, radio was the home of religion on the BBC, faith-based programming on television usually being restricted to short televised sermons on Christmas Day, or carol concerts in December. It had been decreed that religion was something best delivered away from the gogglebox, and as such, a block on all television programming on early Sunday evenings would remain in place until the 1950s.

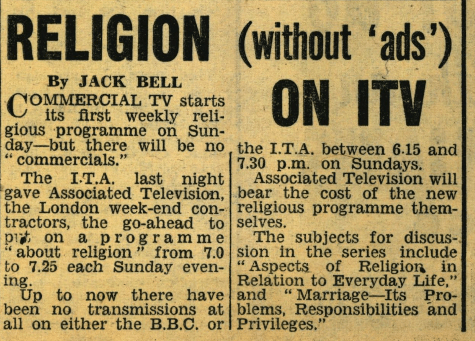

By the early 1950s, religion would become a more commonplace sight on British television. An expansion in Sunday broadcasting hours in 1953 allowed regular Sunday morning broadcasting on the BBC Television Service, and with it the first episode of the long-running Morning Service, the first edition coming from the Moseley Road Methodist Church, Birmingham. For the first time, those unable to travel to church could attend a Sunday service from their own home. In 1955, ITV arrived, turning British television into a duopoly, and the nascent network soon started broadcasting regional sermons from each franchise, along with religious documentaries like About Religion or Living Your Life each Sunday evening.

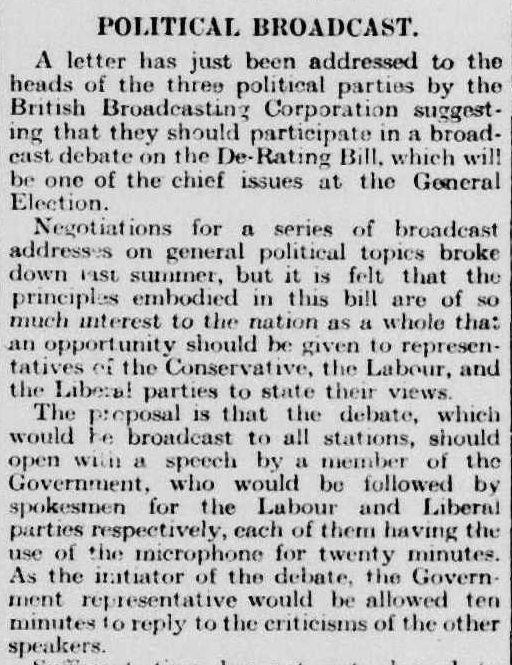

Daily Mirror, 3 Jan 1956 But there was still a hole in the Sunday schedules. Save for a few occasions where the BBC had broadcast an Evening Service, the hours between 6pm and 7pm (generally) saw television broadcasts blacked out, to encourage Britons to get off their armchairs and onto pews. This presented a problem for ITV, who noticed that much of the audience that switched off at 6pm wasn’t tuning back in at 7pm. As a result, the broadcaster lobbied for the removal of the ban, on the proviso that the slot be filled with religious programming, broadcast without commercial breaks.

It took a while before ITV was allowed to fully employ those lost hours, but by 9 March 1958, the 6.15pm break in Sunday broadcasting was finally broken with the first episode of Welsh language hymn compendium Land of Song, a rare network offering from TWW (where it went out under the original Cymraeg title Gwlad y Gan), going out one Sunday in four. It would take another week for the first English-language programme to appear. And so, on 16 March 1958, The Sunday Break broke onto the ITV network, built on the basis of being a televised youth club, featuring dancing, singing and bible readings.

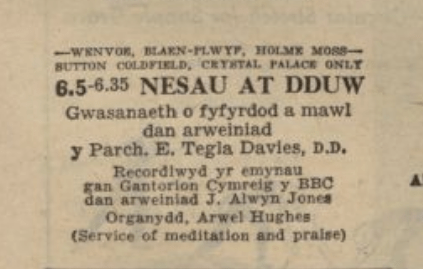

Back on the BBC, it took a while to land on a regular programme to fit that slot. For years at this point, special religious-based programming had been scheduled in that slot to fit in with particular occasions such as Harvest Festivals or Whit Sunday, but generally the hours between 6pm and 7pm on Sundays featured a summary of the weather and a closedown1. Even from 1958, the Corporation would generally offer ten-minute sermon series Sunday Special at 6.10pm before shutting up shop for the remainder of the hour. It took until October 1959 before, in what is fast becoming a running theme, another Welsh-language programme filled that particular gap (or at least most of it).

Even then, this particular service of meditation and praise only aired on a monthly basis. For the other three Sundays per month, it was back to weather and 45 minutes of nowt from the 6pm hour.

This state of affairs continued until 1 October 1961, when a new programme arrived at 6.15pm, and which would become a fixture on British television. That programme was (deep breath) Songs of Praise (“Finally!” – every single person reading this).

The genesis for Songs of Praise came about due to BBC assistant controller Donald Baverstock happening across a recording of hymn-singing in Welsh. Employing the same producer instincts that had previously led him to devising long-running current affairs series Tonight, Baverstock felt it was something that could appeal to the wider UK audience. It also helped that the BBC had accumulated large outside-broadcast units for the purpose of beaming live sport onto Grandstand each Saturday afternoon, but which had little to do each Sunday.

Surprisingly, it seems the main initial naysayers to this new programme were the BBC’s Religious Broadcasting department. Their flagship offering was Meeting Point (726 episodes, 1956-1968), which covered religion around the world, offered serious discussions on the topic and included documentary films. A weekly programme offering people having a good old sing-song was considered to be a little flippant for such a serious topic. However, an episode of Meeting Point broadcast from BBC Wales’ studio, devoted to choirs singing a series of requested hymns, had been one of the programme’s most popular episodes.

Ultimately, the threat of handing Songs of Praise to Light Entertainment made the Religious Broadcasting department come around to the idea, albeit reluctantly.

It was a format not dissimilar to the aforementioned Dechrau Canu, Dechrau Canmol, which had started in a mid-afternoon slot ten months earlier. And, appropriately enough, the very first (television) Songs of Praise came from the Tabernacle Baptist Chapel in Cardiff, the very same city that provided a venue for the very first edition of (radio) Songs of Praise back in 1926. To cap it all, that first edition was even introduced by Rev Dr Gwilym ap Robert, host of… Dechrau Canu, Dechrau Canmol.

Luckily for Donald Baverstock, the gamble paid off. Songs of Praise quickly became the British TV’s most-watched religious programme. From there, the format was a study and unwavering one: an hour of songs, sermons and readings, coming each week from a different place of worship, ensuring a packed house for each venue (and a memorable Not the Nine O’Clock News sketch a couple of decades later).

By the 1970s, ITV had made an effort to add some glam to their God Slot offering, with Stars on Sunday attracting a variety of well-known names to perform appropriately religious readings and songs. BBC1 however remained resolutely loyal to their trusted Songs of Praise format.

Following 1977’s further relaxation in the rules governing which bits of the Sunday schedule were allocated to faith-based programming, BBC1’s Sunday evening schedule became even more predictable. Songs of Praise would run from 6.40-7.15pm, followed by something decidedly different. Initially, there were episodes of play series Jubilee (“reflecting life in the last 25 years”), later followed in that 7.15 slot by The Onedin Line, Poldark and All Creatures Great and Small. By the 1980s, family-friendly sitcoms would occupy the post-Songs slot, with Banana Sandwiches and Tinned Fruit stalwarts Open All Hours, Hi-De-Hi! and To The Manor Born making themselves at home. Later on, a generation of mid-80s kids followed their Sunday night bath with episodes of Ever Decreasing Circles, Last of the Summer Wine and Sorry!. Perhaps the most pleasing offering of all come in early 1986, when 7.15pm became home to repeats of Hancock’s Half-Hour.

Come January 1993, a change to the restrictions on religious programming meant Songs of Praise moved from that rigid 6.40pm slot, and the slide towards being broadcast earlier in the day began. Initially, Songs slipped back a quarter-hour to 6.25pm, meaning subsequent programmes could begin at the neater time of 7pm. January 1996 saw it nudged back to 6.10pm (occasionally 5.55pm), then to 5.40pm a couple of years later, and from 2010 around the 4.30pm mark. Currently airing in an early afternoon slot, Songs of Praise picks up an audience much more modest that in its 1970s heyday, with figures at around a loyal million or so.

In any case, whether you’re a person of faith or otherwise (I’m classed as ‘otherwise’, so I’ve learned a lot from researching this), there’s something comforting about knowing it’s a topic that the BBC is still keen to cover. Indeed, religious programming is a genre that wouldn’t exist on mainstream telly at all these days were it not for the BBC, unless you’re willing to get into the more evangelical fare in the nosebleed section of Sky’s EPG.

No wonder so many people watch it religiously I’M NOT EVEN SORRY.

Another one down. More soon!

Footnotes

1It might not necessarily be a reference to this practice, but the fake TV listings guide for Chanel 9 in The Fast Show book include the following:

-

Mum’s Tape

It’s one of those moments that pretty much everyone prepares for mentally, possibly years or even decades in advance, yet hits you unexpectedly when it actually happens. Last week, that moment happened to me. My mum died.

Obviously, there’s no ‘best case scenario’ for such a life event. Even your mother gallantly sacrificing herself by coaxing a demented robot Hitler into a spacecraft’s air lock to thwart an Earth-destuction plot would hit you like a bastard. But in the case of me and my family, we pretty much knew that moment was coming for some time, even if we all hoped we were massively mistaken. That doesn’t make it any easier (no robot Hitlers were involved, either. Unless they were some bloody convincing disguises).

At the time of writing this, I don’t even think I’ve fully processed it yet. It’s something that keeps barging into my mind, a gut-kicking suffix to thoughts like “must give Mum a ring to tell her about… oh”. Something where little parcels of sadness occur via nondescript events, like how phoning the dentist pushes my last call to mum a notch down my phone’s ‘recently dialled numbers’ list. And, to keep this on topic for the blog, seeing stuff on telly I know she would’ve loved. BBC Two’s recent retrospective of Barry Humphries’ appearances on the Beeb is precisely the sort of thing I would’ve phoned her to make her aware of. That’s because one trait I was lucky enough to inherit from Mum was a general sense of taste when it comes to Things On The Telly.

Usually the de facto rule when it comes to a parent recommending a piece of popular culture to you is that it’s immediately befouled forever. Well, I can’t like *that* anymore. Tsk. But, my dear old mum was frequently right on the money when it came to films and TV that I might like. Which, considering she was more then forty years my senior and therefore from a generation very different to my own (plus, I was annoyingly keen to avoid liking things that would be obvious, because I’m annoying), is quite a feat.

For most of my childhood, my parents ran a working men’s club1 in a small village a few miles south of Wrexham. For the most parts, one parent would keep things ticking over behind the bar, while the other would be keeping me company in the adjoining house. On busier nights both would be required to operate the pumps, meaning that I was afforded free rein when it came to choosing my evening’s televiewing. They clearly understood that I was sensible enough to pick things at least semi-suitable for myself, and that I was thoughtful enough to cope with what I was watching. Apart from the time at the age of ten when I watched Threads on my own, but anyway.

It’s likely this played into my favour at school. As a largely quiet and introspective child, my knowledge of the previous night’s Absolutely, Blackeyes or, um, Life After George provided me with a veneer of respectability in the eyes of my peers. Having that cultural currency seemed to help me skitter up at least a couple of rungs on the social ladder, meaning I eventually escaped school with only a mild sense of depression and self-loathing. Success!

Here, I’ve picked out a handful of programmes recommended by my dear old Mum. Suffice to say, along with the following there were attempts (as any good parent would make) to get me to watch suitably improving fare like The Railway Children, but I’d say that if any children of the 1980s willingly dashed home to watch The Railway Children, I’ve certainly never met them. Instead, these are a few of the much better things Mum recommended to me.

Bedazzled (Channel Four, 23:15 Sat 5 Jan 1991)

Now, it’s quite likely I’d never have stumbled over this myself, following as it did a four-and-three-quarter hour broadcast of Richard Wagner’s operatic epic Der Ring des Nibelungen: Siegfried2. Thanks to the recommendation of Mum, I stayed up way too late watching what would become one of my favourite ever films, with short order chef Dudley Moore lured into an eternal/infernal contract with the devil himself (aka George Spiggott, aka Peter Cook). To think, had I been born a decade later I might have been raised on the Liz Hurley remake. Brr.

Blackadder II (BBC1, 21:30 Thu 9 Jan 1986)

While my mum definitely had a penchant for historical drama series, I’d later find it a little surprising that she’d been so taken with the original The Black Adder that she’d enthusiastically recommend I stay up late to see the first episode of the sequel going out on original broadcast (Jim Broadbent voice: “What was she like?”). Especially so given that (at the time) it felt much more of an alternative outsider offering than the cosy TV classic it would later become, and I was only 11 years old at the time (and it was a school night). You already know that this was definitely the correct decision on her part.

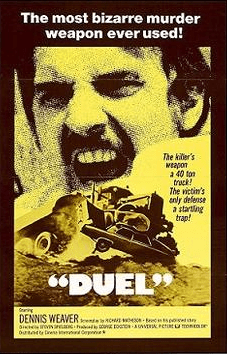

Duel (BBC2, 20:30 Mon 14 Sep 1992)

Not the first film you’d associate Steven Spielberg with – not least as it was made for TV rather than cinema – but this lo-fi affair is every bit as gripping as his later work. And that was definitely the case for my parents when this was first broadcast on BBC2 in October 1975, when their ramshackle rental set decided to go ‘ping’ and suddenly compress the picture into a postage stamp-sized square in the centre of the screen thirty minutes from the end. Undeterred, my Mum and Dad were so determined to see what would happen to Dennis Weaver’s traumatised traveller, they watched the remaining half-hour perched inches from the screen.

Luckily for me, technology had progressed enough by 1992 that I was able to watch the entire thriller without any such concern. And make no mistake, it’s a great film, and one all the better for going into it knowing nothing other than “watch this, you’ll love it”.

The end of analogue television from the Winter Hill transmitter (BBC1, ITV, C4 & Five, Wed 2 Dec 2009)

If ever proof were needed that The Way I Am is down to genetics rather than any learned behaviour, during a phone call from my mum on 3 December 2009, my mum mentioned having stayed up late to see if they’d do anything interesting to mark the shutting down of the local analogue transmitter mast. They didn’t, it just crashed to static in the middle of overnight News 24 coverage. In a perfectly-timed piece of parent-child synchronicity, just days earlier I’d spent an evening writing a lengthy blog post on the exact same topic3 when it had happened to BBC2 the previous month.

Hancock’s Half Hour (BBC1, 19:15 Sun 23 Feb 1986)

Like many kids of my particular vintage, Old Comedy4 was a large part of my television landscape. I was just old enough to experience (and adore) the tail end of Morecambe and Wise’s Thames years, so was delighted when repeats of their BBC shows began in the mid-1980s. Similarly so with repeats of Some Mothers Do ‘Ave ‘Em, Porridge and Dad’s Army. However, perhaps still desperately trying to recover from the expense of setting up colour TV in the first place, any archive programming in black and white was usually the sole preserve of the schedule’s fringes. The likes of The Phil Silvers Show or Leon Erroll would be tucked away in at Too Late O’Clock or Way Too Early O’Clock in the morning, meaning that aside from slapstick compilations of Harold Lloyd or old films (both usually restricted to the niche confines of BBC2), the sensible viewing hours were populated entirely by colour programming.

That changed in 1986, with BBC1’s first primetime foray into black and white archive programming for a number of years, and the last time the channel would ever do so. Following on from a well received Omnibus special on the work of Tony Hancock the previous year, and bolstered by BBC Enterprises’ desire to sell VHS cassettes of Hancock’s Half Hour, the lad himself made a triumphant return to Sunday evenings, with the The Blood Donor (pedant mode: ‘Hancock’ rather than ‘Hancock’s Half Hour’ by that stage, of course) attracting over 15 million viewers. One of whom was me, following an assurance from Mum that I’d love it. Catchphrase on ITV didn’t stand a chance, and a lifelong obsession with events at 23 Railway Cuttings had begun.

People Just Do Nothing (BBC Three, 00:00 Wed 24 Jun 2015)

Even in their later years, the viewing habits of my parents would often surprise me, whether it was Dad using catchphrases from Lee & Herring’s Festival of Fun in everyday conversation (not Fist of Fun, the Just For Laughs coverage they did for Paramount that about 376 people watched), or Mum suddenly displaying a hitherto unannounced knowledge of Hammer Horror films during a BBC2 season of them in the late 1980s.

A peak example of this came as my wife went into both the early stages of labour and hospital with our first child in 2015. The hospital selfishly not wanting me cluttering up their prenatal ward overnight, I left at midnight but needed to get back there as soon as I could the following morning. Living a 45-minute drive from the hospital, I needed to find somewhere closer to crash out for a few hours, and luckily my parents lived just a few miles from there. On arriving at their house shortly past midnight, they were both still awake (they were never morning people), and enjoying the latest antics from the Kurupt FM massive. Because of course they were.

Russell Coight’s All Aussie Adventures (DVD, 2002)