If this blog has a catchphrase, it must be “that took a lot longer than I’d expected”. And this one did. Not so much as down to getting together a programme history of the show in question, but more to do with checking the broadcast histories of the Top Two programmes. And O! The excitement.

On checking through everything, one programme had a large number of broadcasts missing from the database due to being buried under “Children’s BBC starting with…” billings, with the programme title itself in the RT ‘description’. And so, as we’re talking about a programme broadcast more than 10,000 times, it took a lot of checking to see what hadn’t been picked up. So much so, there was a very real chance this next programme might actually have topped the list.

How close did it come to the top? Well, on my initial recheck, if it had been shown just 26 more times, it would be top of the all-time chart. And then, on checking the other programme left to uncover, it looks like several broadcasts couldn’t be counted (due to actually being an unrelated film of the same name). The gap crept ever closer. After all this time, could it come down to a single figure difference? Or even actually end in a draw?

Then I discovered repeats of The Programme At Number One spent three months going out billed as “NEWS followed by… [Programme Title]”, which increased the gap by a load. Hey ho.

But enough of me explaining why Genome ate my homework, let’s take a look at the programme in second place on the list. Apologies to anyone getting this via email – it’s a long one. It’s time to look through the oblong window at:

2. Play School

(Shown 10,575 times, 1964-1988)

When launching a television channel, it’s generally a good idea to pick something really good and important to kick things off. Channel Four had the first episode of Countdown, which everyone remembers. Channel Five had the first episode of Family Affairs, which I needed to look up. ITV, of course, had ‘Inaugural Ceremony at Guildhall‘, which can’t have been that good as it didn’t go on to get a full series.

As the BBC’s first new channel since the launch of the Television Service in 1936, 1964’s plans for BBC-2’s launch night were as fancy as you might expect. Following a brief introduction to the channel, there was the promise of new comedy show The Alberts (featuring, as the RT listing had it, “Ivor Cutler of Y’hup, O.M.P, Professor Bruce Lacey, John Snagge, Sheree Winton, Benito Mussolini, Major John Glenn, Adolf Hitler, David Jacobs, Birma the Elephant (by courtesy of Billy Smart’s Circus) and other celebrities“), followed by a production of Cole Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate. Brilliant. Nothing could possibly go wrong.

Ah.

As fate would transpire, due to a huge fire at Battersea Power Station a mere half-hour before the channel went live, those plans were thrown into candle-lit disarray, and an expectant audience was instead treated to an (initially mute) news bulletin beamed from the nearby but unaffected news studio at Alexandra Palace, as read by Gerald Priestland. That was followed by an evening of captions and apologies. Most British channel launch ever, 10/10, no notes.

And so, as I’m sure you’re already well aware, the first actual programme broadcast on BBC-2 was something commissioned for an audience of under-fives. And, much like Channel Four’s Countdown, it would go on to a very long life on our screens.

Yep, it’s Play School. For a good few generations of young televiewers, a programme that would provide an early introduction into a long fascination with TV. And, personally speaking, the catalyst to one of my earliest distinct memories. On – I think – turning four, in response being told that I’d been born at 11am on my day of birth, I sought confirmation that “I was in time to see that day’s Play School?” Talk about appointment to view television.

The proposal of having a pre-school series in the new channel’s schedules came from BBC2 Head of Programmes Michael Peacock, and by the time of Play School’s launch, the BBC had a new Head of Family Programmes in place to help get those wheels into motion.

Doreen Stephens had been a hugely instrumental figure within 1960s television. Despite only starting her TV career at the age of 40, she’d go on to become Head of Women’s Programmes at the BBC, then (as just mentioned) Head of Family Programmes, before moving to LWT to head up their Children’s, Religious and Adult Education Programming department. Despite initial reluctance in moving away from Women’s Programmes and onto Family Programmes in 1963, she soon revolutionised the department, bringing in fresh faces and minds to help move away from the imperial-era likes of Watch With Mother and introduce programmes like Jackanory, The Magic Roundabout and Play School.

Stephens’ aim was to move away from cotton-wool content like Bill and Ben, instead introducing shows for a generation who’d soon be thrust into the more technical world of the 1970s. Her approach was a success. At a time when the expanding ITV network was bossing the BBC in the ratings, her children’s programmes consistently attracted more viewers than the commercial channel’s own offerings. Indeed, it was that level of success that saw David Frost lure her over to LWT after landing the licence for London’s weekend broadcasting.

A board chaired by Michael Peacock selected Joy Whitby as producer of the new programme. Whitby was duly given a more-than-modest budget of £120 per week (£2,030 in today’s money) to put together five programmes per week, all to be broadcast live. So, in today’s money, that’s a whopping £406 per episode. An unbilled pilot episode of the programme was shown as part of BBC-2’s trade test transmissions on 31 March 1964, presented by Eric Thompson and Judy Kenny. Coincidentally, the script and programme still exist in the BBC’s archives. Y’know, in case anyone working at the BBC Archives is reading this.

All was set for the launch of the full series. The initial working title of Home School had been discarded before this stage, in favour of the friendlier sounding Play School. As programme advisor Nancy Quayle would later explain in the fifteenth anniversary programme Twenty Five Minutes Peace, “play is the child’s first school”.

Whitby had initially joined the BBC to work in their School Broadcasting Department, but working on Play School would be the first of several projects that would land her name in British television history. After liaising with a variety of experts in the fields of childcare, learning and literature to come up with a suitable blueprint, it would go on to win various accolades, including a Guild of Television Producers and Directors Award, and a place in the hearts of children for decades to come. Whitby later left the programme to devise Jackanory (as covered previously) before joining Doreen Stephens at LWT in 1967, but as leaving presents go, the format for Play School is hard to beat.

To outline what parents (and their children) could expect from the new series, Joy Whitby took to the Radio Times.

Joy Whitby introduces her new BBC-2 series beginning today which provides ‘nursery school’ for the under-fives

ARE you an exhausted parent of a child under the age of five? If so, Play School may be just what you are looking for. Without actually leaving home, for half an hour every day (from Monday to Friday, beginning today, Tuesday), your child can benefit from the advice of leading authorities on nursery education and enjoy the undivided attention of a changing panel of presenters-young and resourceful men and women, most of them with children of their own. Play School will not be a televised nursery school-room. It will use all the advantages of television to do the job of a nursery school in its own exciting way. Every day our story chair will be occupied by a storyteller of out- standing talent-in this first week Athene Seyler, followed by Charles Leno, Eileen Colwell, and David Kossoff. Through our magic windows we shall invite children to explore the real world which they long to discover-the world of buses and elephants, flowers and snails, rain and shadows. There will be a Pets’ Corner, a Play School garden, songs, and surprises, and opportunities for joining in both new and traditional games. We hope to offer not just another half-hour’s viewing a day. We want the children who attend Play School to take away from it ideas and stimulation to last long after their television sets have been switched off.

Joy Whitby, Radio Times, 18 April 1964

With the demands of five live episodes per week, running almost every weekday of the year, the decision to use a repertory company of hosts was an obvious one, but each needed to be suited to the role, and the process of getting the right presenters for the programme was delightfully fitting. When Brian Cant, at the time a jobbing dramatic actor, applied for a role in the new series, his audition involved Joy Whitby kicking a box out from under a table and asking Cant to “get in there and row out to sea”. One ad-libbed fishing voyage later, a three month contract on the series was his. Eighteen years later, he would still be a regular Play School player.

In the same way a football squad needs to have a variety of skills and disciplines, Play School’s presenters had a good mix of backgrounds, with Joy Whitby selecting thirteen equally valuable squad members from the off: Virginia Stride and Gordon Rollings (as seen in the first ever episode), Carole Ward, cardboard box interviewee Brian Cant, Judy Kenny, Marian Diamond, Julie Stevens, Terry Frisby (then billed as Terence Holland), the international trio of Rick “Fingerbobs” Jones (Canada), Marla Landi (Italy) and splendidly-named Dibbs Mather (Australia), plus husband and wife Eric Thompson and Phyllida Law. Strength in depth, right at the start of the season.

Each episode had a pairing of squad-rotated presenters, each advised to speak to the camera as if addressing an individual child, an inclusive approach that made viewers feel at home. While the presenting line-up would be freshly rotated, a sense of uniformity was applied each day’s episodes. So, each Monday’s episode would focus on ‘The Useful Box’, Tuesdays would be Dressing Up Day, every Wednesday would focus on pets, each Thursday encouraged viewers to use their imagination, while Fridays would be Science Day.

Another integral part of the new series was each episode’s storytelling segment. Rather than have one of the presenters taking to the storytelling chair each day, a variety of guest storytellers would appear, introducing the young audience to a story, often of their own making. Speaking in 2006 BBC Four documentary The Story of Jackanory, Joy Whitby told of the thinking behind this approach.

“It seemed important to get in and attract people of great quality who might not want to spend all their time doing children’s programmes but who would certainly commit themselves to some performances, and in a way that’s what happened with the storytelling element.”

Joy Whitby, The Story of Jackanory (BBC Four, TX 14/02/2006)

And so, starting with actress Athene Seyler in that very first episode, the storyteller segment would soon go on to feature names such as Flora Robson, Roy Castle, Richard Baker, Quentin Blake and a pre-Dad’s Army Arnold Ridley, with many Play School storytellers later going on to perform similar roles in Jackanory.

Within the first few months of Play School, a decision was made to expand the remit of storytellers beyond the UK, inviting storytellers from other nations to relate children’s tales from other lands. The practice started in July 1964, with British-Pakistani actor and director Zia Mohyeddin taking to the chair to read a selection of traditional Indian fables.

The formula was a success with those able to receive BBC-2, so much so that a special edition of the programme aired on its first anniversary in April 1965, with several viewers (and a baby lamb called Sooty) invited to a special tea party at the Riverside TV Studios. However, by that point the reach of the second channel still only extended as far as London, the South-East, East Anglia and the Midlands (with the episode shown on Midlands’ launch day – 23 November 1964 – featuring a bespoke welcome from presenters Marla Landi & Brian Cant).

Even then, Play School could only be viewed in homes containing 625-line compatible sets. Viewers elsewhere in the UK were finally able to knock on the Play School door in July 1965, with the first same-day repeat of the programme on BBC-1, initially for a trial period running the length of the summer holidays. Such was the confidence in the trial, the afternoon broadcasts of Watch With Mother were paused to make room for it. A whole new set of children would be getting to see the famous Play School windows.

With Play School finally making an appearance in regional copies of the Radio Times that hadn’t been carrying BBC-2 listings, Joy Whitby put together a fresh introduction to the programme, this time being able to include evidence of what they programme had brought to those lucky enough to enjoy it.

For the next six weeks* the afternoon edition of ‘Watch with Mother’ on BBC-1 will be replaced by a repeat of ‘Play School’, the morning programme which is running on BBC-2

Can you remember what it was like to be four years old? Everything you saw was new. But your hands were still uncertain servants. Your feet were not allowed to take you exploring far beyond your own front door. Your mind bubbled with ideas but you did not have enough words to express them. This child you once were is Play School’s target audience.

Turn on your set and you will see – a house. The door opens and lets you into a room which very soon you will feel you know: Humpty Dumpty, Jemima, and Teddy live in the toy cupboard by the blackboard. The shelves are full of books. The picture board might show one of your own paintings one day. There is a corner for pets; a table for scientific experiments; seven pegs carry an ever-changing selection of dressing-up clothes; and a large hamper overflows with useful oddments for making things.

So far Play School offers the standard equipment of any good nursery school. But it also has at its disposal all the imaginative resources of television-lights that can transform a blank wall into an apple orchard, lenses that turn men into giants, film that can show anything from a spider spinning its web to a rocket ship on its way to the moon.

Above all, Play School offers a stream of exciting people-not only experts in the field of nursery education but visitors from the world of adult entertainment. Ted Moult describes his farm. George Melly provides an ABC of jazz. Many accept for the first time the challenge of shaping their material without condescension to the needs of this specialised audience. A team of twelve young men and women present the programmes, pairing up a week at a time with changing partners-a system which keeps the chemistry fresh for viewers and performers.This testimonial from a couple of teachers whose daughter has watched Play School from the start is typical of the many letters we receive from parents: ‘Her imagination has been stimulated, her language enriched and the creative ideas which are a feature of the programme have started her on many an hour of effective learning through play.’

Joy Whitby, Radio Times, 24 July 1965

We hope that this week-with Athene Seyler, Beryl Roques and Brian Cant – what has been true every day for thousands of children on BBC-2 can now be true during the summer holidays for the wider audience on BBC-1.

(*Newspaper reports at the time put the trial run as lasting eight weeks, not six. In the end, the trial ran for a total of eight weeks. Pointing this out doesn’t really add anything of value, but I’ve typed it in now.)

Truly, while Open University would go on to become ‘The University of the Air’, Play School was fulfilling a similar remit for pre-schoolers. Avoiding the maternalistic tone of Watch With Mother, this was much closer to speaking to under-fives at their own level – for all that Bill & Ben, The Woodentops or Muffin the Mule had enthralled audiences, there had been a disconnect between the screen and the audience. With Play School, the children were invited to take part, either by sending in pictures in the hope they’d appear on the Play School set, or by playing along with the activities on screen.

Crucially, Play School was honest enough to avoid the assumption the entire audience were on board with the presentation style. As series producer Cynthia Felgate pointed out, “Talking down is really based on the assumption you’re being liked by the child. But if you imagine a tough little boy of four looking in, you soon take the silly smile off your face.”

The high regard that the series was now held in became clear in September 1965. The BBC had made a landmark agreement with the UK’s three main political parties to televise the Labour, Conservative and Liberal Party conferences in full on BBC-2. This was way beyond the scope of any Party Political Broadcast – each day’s coverage was scheduled to run from 9.30am until the close of the day’s play around 5pm. The agreement came with only one caveat from the Beeb: live TV coverage had to be paused at 11am each morning to make way for Play School. Ted Heath nil, Big Ted one.

Play School was back on BBC-1 throughout the summer holidays of 1966, but this time it would be simulcast on both -1 and -2 at 11am each weekday. That’s an impressive feat considering simultaneous broadcasting was an occasion normally reserved for cup finals and royal events, and even then only because BBC-1 and ITV both wanted a piece of the same pie. On top of that, BBC-2 had recently been made available to the majority of the UK, largely meaning only those still using 405-line sets were missing out. Play School was certainly becoming what is known as A Big Deal.

As adoption of BBC-2 increased, Play School was confined to the channel for the next few years, until in November 1968, when Play School started being repeated on a long-term basis on BBC-1 – in the peak post-school time of 4.20pm to boot, albeit only on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays. Tough luck if your home was lumbered with an antique television on the other weekdays, but at least you could spend your Monday and Wednesday afternoons watching vocationally improving fare like Training In Skills or Teaching Maths Today in that same slot. You know, for the really smart under-fives.

By this point, Play School had started going out in full colour on BBC2 (at least on most days, when they were able to use one of the BBC’s colour-capable studios), which helped bring a welcome dash of colour into the worlds of the young audience, and making all that imagination-fuel that bit more vivid.

Many of the cast of presenters would go onto other roles as a result of their time on Play School. Britain’s National Cool Uncle Johnny Ball would move onto a career of winsomely accessible maths, logic and science programmes like Think of a Number, Think Again and the troublingly-titled Johnny Ball Reveals All. The comic chops displayed by Fred Harris led to a brief career change in Marshall and Renwick’s radio comedy The Burkiss Way and LWT’s Burkiss-in-all-but-name sketch comedy End of Part One, before becoming the BBC’s friendly face of computer literacy throughout the 1980s. Meanwhile Brian Cant – long before his memorable stint on This Morning With Richard Not Judy‘s The Organ Gang – moved onto Play School’s first spin-off series, Play Away (broadcast 308 times, 1971-1984).

Play Away was a much, for want of a better word, ‘looser’ affair than Play School, with a heavier emphasis on songs, slapstick and puns than its parent series. As befitting Play Away’s more relaxed aesthetic – a bit like seeing your teacher in the supermarket wearing civvy clothing – it mostly went out on Saturday afternoons, but would get occasional repeats on weekday Children’s BBC, and built up quite a noteworthy cast during its time on air. Regular Play School players were the faces most familiar to the audience, namely Brian Cant (who featured throughout the entire 1971-84 run), Derek Griffiths (1971-73, 1975), Chloe Ashroft (1971-79), Julie Stevens (1971-79), Lionel Morton (1971-77), Carol Chell (1971-80) and Floella (now, of course, Baroness) Benjamin (1977, 1979-84).

There was also room for a fresh intake of Play Away-only players, including (as surely everyone knows by now) a pre-fame Jeremy Irons, but also early gigs for Julie Covington, Anita Dobson, Tony Robinson and Alex Norton. And, despite initially being studio-bound, later series of ‘Away would feature (and heavily involve) an actual studio audience. Plus, the entire run of the series featured Jonathan Cohen heading up the Play Away Band. Quite the ensemble, all in.

Of course, you don’t get anywhere by standing still, and Play School wasn’t afraid to move with the times. For example, the famous title sequence (“Here is a house…”) underwent more regenerations than The Doctor during it’s time on air (well, more or less), the animation often being updated to keep things fresh (if reliably hauntological for much of the run).

Of course, Play School wouldn’t have been Play School without the involvement of the Play School toys. Inanimate, they may be. Mute, unashamedly so. Integral? Definitely. So, let’s take a moment to mark the input of Humpty (who first appeared in that very first episode on 21 April 1964), Jemima, Big Ted (originally named ‘Teddy’), Little Ted, Dapple the Rocking Horse, Poppy, Bingo the sock dog and Cuckoo. Oh, and not to forget Hamble, terrifying tots since that first ever episode. Co-stars who were at least a little more active were the Play School pets, expertly looked after by Wendy Duggan from 1965 onwards.

February 1983 saw the introduction of a short-lived companion programme, in the form of Play School Play Ideas. Having originally been a series of spin-off books first published in 1971 (and written by the appropriately-named Ruth Craft), each ten-minute episode ran before regular episodes of the series, but was targeted more at parents who wanted to be ‘one jump ahead’ on some of the ideas from the series. Looking for a choice of recipes for finger paint or play dough? Or a heads-up on the bits and pieces needed to play some of the games at home? Or even some personal feedback from a teacher on the value of the series to nursery attendees? Then this eight-episode series was very much for you.

A larger change came later in 1983, when series editor Cynthia Felgate marked the programme’s move from BBC-2 mornings to BBC-1 mornings (making way for Programmes for Schools and Colleges, which travelled in the opposite direction) by a more literal house move for Play School. A brand new set (sorry, ‘house’), a new theme tune (and accompanying dialogue), plus a switch from two to one main presenter each day, with various guests popping in each week. The new jazzier stylings of the series certainly helped keep things fresh, but time was running out for Play School.

29 March 1985 saw the last Play School going out as part of the afternoon Children’s BBC schedule, meaning the programme was now a solely morning treat once more, though that was offset by Sunday morning broadcasts of highlights from the previous week. Play School continued in this vein for a few more years (still showing sufficient importance to punch a twenty-minute hole in daily Party Conference coverage each autumn), but there was now an acceptance that slightly older children coming home from school no longer had much interest in the series.

When the end came for Play School, it was at the hand of someone who’d been there at the beginning. Anna Home had been a part of the production team right from the very beginning, before moving on to produce Jackanory, plus drama serials such as Carrie’s War, The Canal Children and The Changes. By 1988, Home had become Head of Children’s Programmes, and felt that at the 1990s loomed, Play School was still slightly stuck in the past. Another Play School stalwart delivered the final blow. Cynthia Felgate’s production company Felgate Productions picked up the contract to make the new totem for under-fives: initially called Playbus (later Playdays), which would go on to have quite an impressive run of it’s own. And so, between March and October 1988, a variety of Play School episodes were repeated while energies were concentrated on its successor.

And so, that was the end of Play School. Between 1964 and 1988, it had featured a total of 104 presenters (94 in the original run, 10 in the post-83 reboot), 54 guests, and six clocks. It saw episodes recorded in the Riverside Studios, Television Centre, Lime Grove Studios, Manchester’s Dickenson Road and Oxford Road studios, plus Pebble Mill. It even earned a quartet of repeat broadcasts (all from Christmas 1985) on short-lived digital channel BBC Choice over Christmas 1999 and 2000. Such was the regard the series would still be held in, the Riverside Studios would play host to a Play School reunion in May 2014, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the series. Previous to that, the 2010 Bafta Children’s Awards saw a special award presented to Brian Cant.

Except: it wasn’t quite the end. Such as the success of the series in the UK, overseas broadcasters had been very keen to bottle some of that magic. The Australian version of the programme first aired in 1966, and is still airing on ABC Kids to this day, making it the longest-running children’s show in Australia (and second-longest in the world, after our very own Blue Peter). New Zealand’s adaptation of the series ran from 1972 to 1990, using the original 1964 UK branding for the series throughout.

Non-English speaking countries also got in on the act, with Switzerland’s Das Spielhaus running from 1968 to 1994, Austria’s Das Kleine Haus (from 1969-1975) and Spain’s La Casa del Reloj all getting in on the act. While some of the remakes were wearing pretty loose-fitting clothing (the Swiss version had talking puppets throughout, which is all wrong), some adhered a lot more closely to the original. Such as the Norwegian version Lekestue, which stuck very closely to the original Play School formula.

With such a rich legacy, it’s comforting to know that Joy Whitby’s original low-budget formula would go on to nurture young minds not just in the UK, but around the world. In fact, it’s probably fitting to give the final word to Joy herself.

“Great to see Play School at number two in your list and to know that Jackanory has also made the top ten. What a wonderful testament to the original team who set the template in 1964. It’s gratifying that the programme continues to hold a place in viewers’ hearts with fond memories of all those talented people, both in front and behind the camera.” (Joy Whitby, January 2024)

So, that’s it. The TV programme shown almost-most frequently within the BBC’s entire history. But what’s at number one? Let’s find out right now, shall we? It’s time to join those…

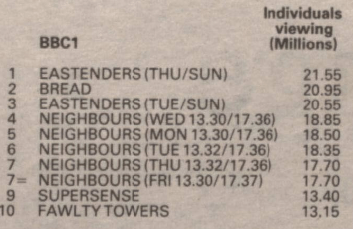

1. Neighbours

(Shown 10,626 times, 1986-2008)

Oh, the irony. Despite using the title ‘The Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes of All-Time’, the programme at number one was a show originally made by and shown on… Australia’s Seven Network. Not even a BBC co-production. So, it’s really the case that Play School is the most-broadcast BBC programme of all-time. It was just pipped to the post by Neighbours. Which, er, isn’t a BBC programme.

That said, the top programme on the list isn’t entirely divorced from British television. Reg Watson, the original architect of Ramsay Street, had created an impressive roster of continuing drama in Australia, such as Prisoner (suffixed ‘Cell Block H‘ in the UK), The Young Doctors and Sons and Daughters, single-handedly filling approximately 36% of ITV’s airtime between 1986 and 1994. But long previous to all that, 1955 saw a tyro Watson leave Australian shores for the UK, and a role at the nascent ATV Midlands. After an initial spell behind the camera directing fare like Noele Gordon ad-magazine Fancy That, then producing the likes of chat show Lunchbox and Godfrey Winn Speaking Personally, Watson championed a proposal for a new weekdaily soap opera devised by Hazel Adair and Peter Lingset.

It was set in the Midlands region – always handy when ATV needed to prove it wasn’t wholly fixated on its London weekend franchise – and was called The Midland Road. Unfortunately, this was in 1958, when a combination of limited broadcasting hours and moneyed franchise holders determined to get their content on screen meant there was limited space in the schedules. It would take until November 1964 before The Midland Road finally reached TV screens, initially in the ATV Midlands region. That is, once it had changed its name to Crossroads.

Watson produced Crossroads for just under a decade before returning to Australia for a role as Head of Drama for storied soapmongers Reg Grundy Productions. The person responsible for that move? Bob Monkhouse. Yes, really. Well, kinda.

During Watson’s time working for ATV, a certain Mr Reg Grundy was enjoying his Mayfair honeymoon with his bride, Joy Chambers-Grundy. During that spell, the newlyweds met with expatriate and future TV-am tyrant Bruce Gyngell, then working for ATV. Gungell introduced the couple to current ATV big draw Bob, who invited the Grundies over to his St. John’s Wood home for dinner. Ever the gracious host, Monkhouse followed this up with an invitation to ATV’s studio to attend a recording of his hit series The Golden Shot, but not before treating the couple to dinner at the Albany Hotel. To make them feel at home, he also invited along a couple of Australian expats working at the channel – Golden Shot director Mike Lloyd, and… Reg Watson.

The Regs immediately hit it off, and with Grundy planning the formulation of a drama department within his media empire, Watson gave his new friend a crash course in putting together a successful serial. Subsequent trips to the UK saw Grundy seek out Watson for added guidance and advice. The guidance was even more pressing once Grundy’s first proposed drama serial – Class of ’74 – was being devised, mainly by staff more used to working on game shows. Grundy would collate together scenes from the series and get them over to Birmingham for Watson’s input. While Watson’s long-distance advice was valuable, the communications network of the mid-70s was hardly instant.

Ultimately, Grundy flew back to the UK to try and coax Watson back to his motherland, if only for as long as it took to help with a flailing Class of ’74. His mission helped by the fact Lew Grade hadn’t got around to renewing Watson’s contract, Grundy offered Watson a much more generous lifestyle than the notoriously penny-pinching ATV, and an initially sceptical Watson agreed to switch 1970s Birmingham for Sydney’s Bayview.

By the 1980s, Reg Grundy Productions (or as it now was, ‘The Grundy Organization’) was responsible for around 25 hours per week of content on Australian TV – a remarkable amount for an indie production company. In addition to soaps, Grundy quiz shows – both homegrown and adapted from overseas originals – were peppered throughout the TV listings, with Sale of the Century, Ford Superquiz, The New Price is Right, Family Feud, $100,000 Moneymakers and Wheel of Fortune attracting loyal audiences.

The Organization (yes, with a ‘z’) also made the move into foreign markets, setting up offices in New York, LA, Hong Kong and London, producing programming for local networks. Beyond TV, the GO had moved into areas such as travel, restaurants, a record label and radio. Basically, with noses in all manner of businesses, the many-headed Grundy business hydra seemed to be unstoppable.

For the drama-based portion of this success, credit goes to Reg Watson’s uncanny ability to devise winning drama formulas. Albert Moran’s book Images & Industry: Television Drama Production in Australia (Australian Screen, 1985) put Watson’s wizardry into context, with some quotes from an unnamed producer within Grundys:

Take Prisoner, for instance. Grundys were approached by Channel 10: “We’re interested in a show, we’d like something vaguely prestigious, Australian oriented. We want it to run one hour per week for sixteen weeks and then we’ll stop.”

So [Ian] Holmes or Reg Grundy gets on the telephone and rings Reg Watson and says, “I’ve made a deal – quick, think of something.” So Reg with his instinct for the audience goes to work, sweats a lot and tears his hair out, goes even greyer and comes up with three or four ideas that he thinks will work. And he puts them to the channel. The Channel picks one and says: “Yes, we’ll go with this.” They ring up. The whole organisation goes into a panic. “They’ve picked X, what are we going to do?”

It’s at that point that Reg sits down at his typewriter and tries to think up a plot to fill in the concept… he wrote a plot for the first episode that was full of short zappy scenes, zappy to stop you thinking about any of them, seventy zaps in forty-five minutes. And then hacks like me are left to make it credible.

Images & Industry: Television Drama Production in Australia, 1985

Watson’s transcontinental transfer to Grundys had certainly been a timely one. With Class of ’74 already on air by the time he arrived, the problems with the series were clear (despite early rushes being flown to Birmingham for input from a Watson working through his three months notice). Despite attracting a lot of initial attention, ’74 (later renamed Class of ’75) would see a swift ratings decline and be axed within 18 months. Conversely, The Young Doctors, the first drama serial to be devised under Watson’s tenure, would run for seven years and 1,397 episodes. That was followed by 1977’s The Restless Years (four years, 780 episodes) and 1979’s Prisoner (seven years, 692 episodes). It soon became clear that the ribbon in Watson’s typewriter had been personally inked by God.

In Reg Grundy’s autobiography, the TV mogul refers to the hiring of Reg Watson as “the most important appointment I ever made”. One example of typical Watson foresight came when Watson floated an idea about a new serial to Grundy: “I’ve got this idea for a drama about three families. The whole concept is about communication between the generations.” From small acorns, eh? And indeed, despite the common conception many held about Neighbours (yes, we’ve got there at last), it was a boundary breaking premise in many ways. Borne of Watson’s time working on Crossroads – and his admiration for Granada’s Coronation Street – this was a programme that would become, at least to British eyes, the quintessential Australian drama series.

And while the programme itself would soon evolve, that principle of focusing on Ramsay Street’s three families would remain key. One such family was led by self-employed plumber Max Ramsay, whose grandad gave the street its name; next door is widower Jim Robinson, raising four kids with the help of mother-in-law Helen. And, aside from the feuding Ramsays and Robinsons, the third focal point of Ramsay Street was the home of twentysomething bachelor Des Clarke, who’s just rented a room to Daphne Lawrence, who, it turns out (cover your children’s eyes) is a stripper. The Sullivans it ain’t.

As Watson himself would go on to point out, “it changed the way we thought in serial drama. In one of the opening episodes, the grandmother was painting and the grandson was sitting for her. He casually said to her, “Grandma, when you and Grandpa were dating, did you have sex?” Normally, we would have her throw the paintbrush down and say, “Look, I don’t want to discuss this”, but we went the other way and she discussed it with him very sensibly.”

Having been bought by the Seven Network, the new series started promisingly. At least, it did in Melbourne, the setting for the series and focus of Australia’s TV industry. It fared less well in Sydney, where slipping ratings saw it moved from a 5.30pm slot to an earlier home at 3.30pm – hardly ideal for the multi-generational audience the programme was hoping to attract.

Then, something surprising happened, especially for a show devised by Reg Watson: the series was cancelled by Seven, after just 170 episodes. Then, as far as the Australian TV industry was concerned, something even more surprising happened – this supposed flop of a serial drama was picked up by rival network Ten.

The move was far from straightforward. Despite supposedly no longer wanting anything to do with the series, Seven threatened to sue Grundys over selling a series the network claimed to own the rights to. On top of all that, an accidental fire had destroyed the permanent sets used for the series. Any legal issues were eventually settled, and the series was given a more youth-focused revamp before arriving on Ten, at a much friendlier time of 7pm.

The revamp saw new characters, new sets and a cast comprised mainly of unknowns, such as Jason Donovan, Guy Pearce and Kylie Minogue. Whoever they are. Plus, it kept key actors from the original incarnation of the series, such as the actors who’d go on to play Vice President Jim Prescott in 24, scheming Yorkshire industrialist Charles Widmore in Lost, Secretary of Commerce Mitch Bryce on The West Wing and the Australian ambassador in Flight of the Conchords. Or, if you prefer, Alan Dale.

And, chronologically speaking, this is where the BBC comes in.

Previously, if there had been anything being shown on daytime BBC1, it would be Programmes for Schools and Colleges, the News, programming for pre-school children, Welsh language content (at least until S4C came along) or Pebble Mill. Occasionally, there’d be live sport, or a political party conference, but aside from that, it would generally be the test card (or Pages from Ceefax by the early 1980s) taking up those afternoon broadcasting hours. That was even the case after broadcasting hours were relaxed to allow for a daytime TV service, meaning ITV franchises were free to put out uninterrupted programming from early morning to late night from October 1972. But, without the increased ad revenue of their rivals, the BBC largely kept away from uninterrupted daytime TV for more than a decade.

By the mid-1980s, BBC1 at least had Breakfast Time to attract an early audience, and gradually, more programmes began to grout the gaps between the end of breakfast TV and the early afternoon Play School repeat, especially now the Schools programming had moved over to BBC2.

For instance, plucking out a random midweek line-up from late 1984 reveals Lyn Marshall’s Everyday Yoga and The Yugoslav Way from 9am, a splash of Ceefax at 9.40am, the day’s first Play School at 10:30, BBC Asian Unit regular Gharbar at 10:50, more Ceefax, the afternoon News and Pebble Mill, pre-school lunchtime distractions Gran and Stop-Go!, followed by the early afternoon coupling of Blizzard’s Wonderful Wooden Toys and Star Movie: Joan Fontaine in Sky Giant to take viewers up to Children’s BBC at 3:50pm. It was certainly a lot of stuff, but not a very clear through-line. Especially when ITV were offering a more consistent line-up, including scripted content for grown-ups like The Sullivans, A Country Practice, Take the High Road and Sons and Daughters. In short: the BBC needed to improve its daytime output. And some of those programmes ITV have got their hands on sound interesting. Hmm.

And so, from 27 October 1986, BBC1’s first true daytime line-up made its debut. This was offered a lot more uniformity than the previous ragtag collection of content, with the daytime dominated by original – if inexpensive – programming.

The full-fat daytime line-up wasn’t yet in place, meaning there was still a couple of curios in the 9am hour (Who’s A Pretty Girl Then?, looking at the 1983 Miss Pears competition, followed by magazine programme for disabled people One in Four) before the main daytime schedule kicked off at 10am, with Pamela Armstrong introducing the new daytime service via All in the Day, offering previews of what you might expect to see each morning. After the regularly scheduled children’s programming at 10:25, there was the first episode of long-running thought for the day strand Five to Eleven, with Dora Bryan the inaugural thought-thrower, followed by a special episode of Gardener’s World.

Bob Wellings, Pattie Coldwell and Eamonn Holmes introduced the first episode of Open Air at 11:30 – hard to imagine a daily hour-long programme that talked purely about television nowadays, isn’t it? That was followed by Star Memories, where a top celeb (in this instance Su Pollard) shares their favourite television memories with Nick Ross, new-look bulletin the One O’Clock News and… the first episode of “a new series with all the day-to-day drama of life in a Melbourne suburb”.

While the BBC’s budget didn’t stretch to a homegrown soap along the lines of Take the High Road, it could certainly afford to pick up one imported from Australia. After all, it seemed to be working out pretty well for those lot on ITV, and given this one had been dumped by its original network down under, it was unlikely to have cost a fortune. EastEnders was doing a roaring trade for the channel, proving that viewers would keep coming back for episodes of a soap on BBC1, and the antipodean import provided a superbly sunny counterpoint to the cold concrete of Albert Square.

Talking of cheap, the new daytime schedule could save a few more shillings by repeating the previous day’s episode of Neighbours at 10am each morning. At least it would give people another chance to catch the new acquisition, and it was hardly as if the programme had arrived with any sense of fanfare. On the day of Neighbours’ BBC debut, that day’s Daily Mirror weekly Soap Opera column failed to even mention the series*, while the first column inches spent on the series by the tabloid – a week after the debut episode aired – saw it dismissed as a programme that “could halt emigration to Australia”. In short, certainly not something that would stick around for years, and – say – see a feature-length supercut of early episodes being broadcast on the tenth anniversary of the programme’s channel debut. Heck, no.

Much like how unhelpful schedulers helped Neighbours get canned by Seven, some of the programme’s racier content (by 1986 standards, which is basically just people using the word ‘sex’) appearing adjacent to King Rollo attracted a certain amount of criticism, but luckily the See-Saw strand soon moved over to Daytime on Two. Indeed, the very content that some were unhappy with proved to be catnip to a growing audience of teenage viewers, especially once the youth-friendly post-revamp episodes started airing. The problem was, they were only able to enjoy the programme when sick or on school holidays. What could be done?

As fate would have it, while Daytime on One had settled into a nice little routine, the early-evening 5:35pm valley between the end of Children’s BBC and the start of the Six O’Clock News was peppered with a variety of ill-fitting formats. Throughout 1986 and 1987, it had played host to repeats of The Flintstones, mid-table syndicated sitcom Charles in Charge, teen quiz First Class (which I’ll wager many kids only watched for Konami’s HyperSports and Atari’s Paperboy), winsome Bill Oddie fact-fest Fax!, put-you-off-your-sausages documentary Hospital Watch, [Disgraced Entertainer] Cartoon Time, Kickstart-in-canoes Paddles Up, The Horse of the Year Show, Rippon-fronted pseudo pub-quiz Masterteam, Muppet Babies and Roland Rat – The Series.

Basically, you didn’t know what to expect while you were coaxing some ketchup onto your mash, and basically nothing seemed to stick around long enough to build an audience. But what DOES that teenage post-CBBC audience want? Step forward typical British teenager Alison Grade.

Alison and her friends had a favourite programme, but it was inconveniently scheduled right in the middle of the school day. This meant that a little creativity was needed if they were able to catch it. Instead of going out to play at lunchtime, they’d find a classroom containing a television, occupy it and tune in. That is, until their scheme was rumbled and a ticking off was issued. Alison returned home that afternoon and told her parents about the incident, and bemoaned the fact their favourite programme was being put out at such an inconvenient hour.

Which, in fairness, is a good idea if your dad happens to be Controller of BBC1 at the time (me saying ‘typical British teenager’ was all a ruse). Speaking in 2021, Michael (now Lord) Grade remarked on how he went into the office the next day and announced “We’re moving Neighbours to 5.35pm, so the kids can watch it when they come home from school”. To pick Neighbours for that original daytime line-up, Grade’s team had scoured through potential imports from around the world before Grade settled on the Erinsborough-based show. The decision to move it to teatimes had arrived in an instant.

The 5:35pm weekday slot was to be taken by the Australian import from Monday 4 January 1988, where it could attract a whole new audience – not that the daytime audience were being left behind. Each episode continued to air for the first time at 1:30pm, as before, all that was effectively changing was the repeats were moving from 9am to the teatime slot.

This presented a fresh problem. With around 300 episodes of the series already being shown, how would new viewers get up to speed on all things Ramsay Street?

Cue Madge Mitchell. Well, Anne Charleston.

To help wrap up the two years of plotlines the new audience had missed out on, Ramsay Street’s very own Madge made the trip to Television Centre to fill everyone in on what they’d missed. Meet the Neighbours only afforded Madge five minutes in the schedules to get everyone caught up, but had a pretty important place in it. 8:10pm on a Saturday night between Paul Daniels and Bergerac.

From there, Neighbours quickly became a firm favourite for millions. Many millions. By the end of 1988, it was regularly posting ratings around the 18 million mark, effortlessly spending most weeks dominating BARB’s BBC1 top ten.

Meanwhile, programme stars Kylie Minogue and Jason Donovan stood astride the world of pop.

To cap all of that, Neighbours would receive one of the highest accolades ever afforded a soap opera: the cast were invited to take part in the 1988 Royal Variety Performance. Does their skit start with someone saying “G’day”? You bloody bet it does.

In a similar manner to how Play School remained superglued to the schedules during Party Conference season, Neighbours had become so ingrained in the BBC schedules that that the afternoon broadcast even interrupted Bank Holiday Grandstand. Take that, Texaco One-Day International from Lord’s!

For the record, only a few occasions were deemed big enough to knock Neighbours out of its lunchtime showing and force everyone to come back at 5:35pm (or later if you’re in Northern Ireland, of course) – or even tune in early when it’s the evening repeat that’s gone AWOL:

Fri 10 April 1992: Rolling afternoon coverage of the 1992 General Election, meaning viewers had to wait until teatime to see the episode where “Harold and Marge want to have their cake and eat it.”

Fri 25 December 1992: The first of only two occasions where Neighbours was deemed big enough for BBC1’s Christmas Day schedule, but only for the lunchtime showing – the evening slot was taken up by Bruce Forsyth’s Christmas Generation Game.

Mon 6 June 1994: Lunchtime broadcast shoved aside for D-Day Remembered, a live international event of commemoration. Hosted by President Mitterrand (presumably the event, rather than the programme).

Mon 25 December 1995: Christmas Day again, and the last appearance of the programme on December 25th. Just in a 12:25 slot, with the early evening taken up by the premiere of Hook.

Thurs 1 January 1998: Bit of a surprise here. It’s New Year’s Day, and again, Neighbours in only on at lunchtime due to the 5pm hour being dominated by From Grange Hill to Albert Square… and Beyond, a programme marking Grange Hill‘s 21st anniversary. Could Neighbours’ grip on the schedules be slipping? Up to that point, the first day of the year (when it fell on a weekday) was no obstacle to a double visit to Ramsay Street.

Thurs 29 June 2000: Only room for an early afternoon showing here, with Wimbledon 2000 and a Euro 2000 semi-final taking up the bulk of the afternoon and evening.

Thurs 20 June 2002: Royal Ascot tramples over the afternoon visit to Erinsborough.

Wed 16 and Fri 18 June 2004: Euro 2004 matches take priority in the evenings, meaning just the daytime showing is broadcast. By this point, The Weakest Link was airing on BBC2, and was rapidly becoming the Beeb’s latest can’t-cancel offering.

From this point on, the act of Not Showing Neighbours became a lot more commonplace on the BBC. World Cup on? Well, people can just watch the episode that’s on later for a few weeks. Bank Holiday? We’re not waiting an extra half-hour to show 102 Dalmatians at teatime.

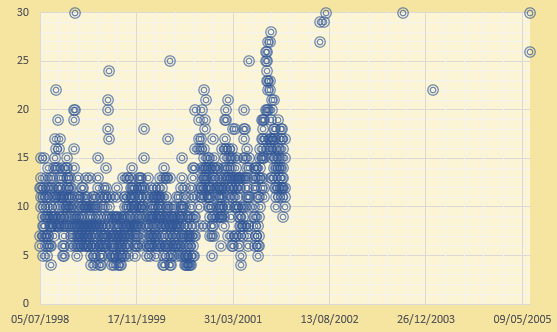

By this point, Neighbours was becoming much less of a draw for the British public. Ten years on from the viewing figures regularly topping 18 million, most episodes were being watched by less than half as many. And, tellingly, other BBC1 programmes were clambering above it in the viewing charts. Without going into a load of detail, here’s a chart showing how often Neighbours appeared in the BARB Top 30 programmes on BBC1 each week, from July 1998 (the earliest week where figures are online) to June 2005 (the last week Neighbours would appear in that Top 30).

There’s no denying that the programme became much less present in these figures from 2002 onwards, after which it practically disappears from view. While that’s partly down to a change in the way figures were listed (viewer numbers were only counted for individual broadcasts from Jan 2002 onwards, rather than aggregate figures for all broadcasts of an episode), that did little to dampen figures for BBC1 stablemate EastEnders, and more important, those viewing figures were already falling. Even with afternoon and evening figures combined, the daily totals were falling, down to around a combined 5 million per day by 2007, and a number that would only sneak into the bottom rung of the chart were aggregate totals still allowed.

And that makes what else happened in 2007 a bit of a shock for the BBC. FremantleMedia, the company then under the conglomerate RTL umbrella responsible for distributing the programme, was set to renegotiate the Beeb’s contract for the series. With ratings slipping, surely they’d ask for a freeze in the sum involved, at most? Instead, they (reportedly) tripled the asking price: a grand sum of £300m for the next eight years of Neighbours. BBC1 controller Peter Fincham went public about the asking price, and declared that Neighbours would be leaving the BBC the following spring. Who would step up to take on the series? The then RTL-owned Channel Five, where it would ultimately stay for the remainder of its time as a broadcast TV programme in the UK.

And so, that was the end of Neighbours on the BBC. It was the channel where the nation – or at least fifteen million-ish inhabitants of it – fell in love with the series. Those who were glued to the series at the time will have their own collection of favourite moments, but here’s my Personal Top 15 Neighbours Moments of All Time. Why not post some of your own in the comments?

15: Seeing someone off Prisoner Cell Block H appear in Neighbours. Of course, it all depends on where your own ITV region was up to in the series. (“It’s Chook!” when Susan Kennedy ( Jackie Woodburne) made her debut)

14: Gayle and Gillian Blakeney (aka the Alessi Twins) appearing in a Pop Will Eat Itself video.

13: Lou Carpenter’s (Tom Oliver) feud with Harold Bishop (Ian Smith)

12: Josh (Jeremy Angerson) tries to win the heart of Beth Brennan (Natalie Imbruglia) by buying her… a copy of military flight simulator F29 Retaliator as she’s ‘into computers’

11: Julie Martin (Julie Mullins) getting killed off. Harsh, but a nation’s common rooms rejoiced.

10: The many regenerations of Lucy Robinson (Kylie Flinker, Sasha Close, Melissa Bell)

9: The times companies paid for product placement in the series knowing their product would eventually reach 15 million viewers on BBC1. Made sense when it was Ocean Software (see 12), not so much when it was Craftmatic Adjustable Beds.

8: The various wizard wheezes of Rick Alessi (Dan Falzan)

7: Seeing someone off Neighbours in Prisoner Cell Block H, normally Harold Bishop (Ian Smith)

6: Finally getting to see Mr Udagawa (Lawrence Mah)

5: The haphazardly-exorcised-on-the-BBC incest storyline

4: Bogan-turned-treasure Joe Mangel (Mark Little) plants marijuana in Mrs Chubb’s (Irene Inescort) garden for a laugh

3: Mrs Mangel’s (Vivean Gray) portrait

2: Chris Lowe (playing himself) roaring into Ramsay Street

1: Bouncer’s dream

WE GOT THERE. Wahey! I’ll be back soon with some post-match analysis – wondering what the chart would look like if I only included primetime broadcasts? And lots more exciting mini-lists? – but for now I need a rest. Cheerio!

8 responses to “The Two Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes of All-Time: The Grand Final”

Buses and elephants, flowers and snails, rain and shadows.

Of course we were all rooting for Claystool to top the chart as it’s among our first telly memories, but, hey, good on yer Neighbours – the soap that launched a thousand celebs. And how many weddings have resounded to the tunes of Mr Anderson or Messrs Stock, Aitken and the hitman?

My daughter recently posted in a family WhatsApp group:

“Anyone know baroness floella Benjamin from ‘playschool’? She’s giving a speech at a conference I’m at with my college”

Older members of the family all got very excited, particularly when it turned out Humpty himself had accompanied Baroness Benjamin. Sadly he wasn’t doing autographs or selfies. Some personalities are beyond mere fame and can only be considered legendary.

Thank you for the incredible feat of producing this chart rundown. It has been, in the true manner of the BBC both informative and entertaining. It’s definitely worthy of a book deal – I’ll watch with interest what develops.

LikeLike

Well done! An absolute tour de force, and I echo Seb’s remarks. Not just a book deal – it’s worthy of a theme night on BBC Two, or even an entire season on BBC Four.

I had Play School at #3, Neighbours at #2, with Newsnight at #1, so I had them in the right order, even though I really wanted Play School to win!

LikeLike

Thanks both! A book deal would be nice, but I think putting something together on Lulu is definitely worth doing…

LikeLike

Thank you for doing this – a real labour of love. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

ITV next?

LikeLike

I don’t think there’s an ITV equivalent of BBC Programme Index – or if there is, it’s not available to the general public.

This exercise would be a lot harder to do for ITV in any case, because of the regional structure of the channel. For about the first 50 years of ITV’s existence it was a patchwork of 15 different regional companies and many programmes weren’t networked. The winner would probably end up being something like “University Challenge” because it was shown in so many different time slots by so many different companies.

(Either that, or something like “Gus Honeybun’s Birthdays” which was shown extremely frequently, but only in one region!)

LikeLike

Our family nest Neighbours moments:

Susan Kennedy falling in a hole.

Toadie being hit by a bouncy castle and being paralysed due to a bullet lodged in him.

Kyle looking at a solar eclipse and going blind

Donna invents the shrugalero

Susan trying to be surrogate for her daughter Libby’s baby

The Cody, Todd, Melissa triangle

Connor learning to read with Spike the Dragon

Dr Nick telling Paul he had cancer so he’d find his research

Karl being the specialist in every medical area in the hospital.

LikeLike

[…] putting together the write-up on Play School – the most-broadcast BBC programme of all time, of course – I used a variety of sources for background. Old issues of the Radio Times, the […]

LikeLike

[…] now the Big Final Reveal is out of the way, and we’ve identified the two programmes broadcast more than any other on […]

LikeLike