Into the top five. And where some programmes in the list are hard to find out much information, he’s one where there’s way too much to feasabily include. Still, here’s a good old bash at it – get comfy for over 6,300 words about…

5: Cricket

(Shown 6250 times, 1938-2021)

PROLOGUE: A lot to get through here, but if you’d like even more detail on the history of cricket on BBC TV, take a look at the book “…and welcome to the highlights: 61 years of BBC TV cricket” (by Chris Broad and Daniel Waddell, 1999) which goes into even more detail, and which has been a huge help on writing this update.

By WG Grace’s soupy beard, we’ve reached the last sporting entry on the rundown, and it’s a biggie. Something that has aired on BBC Television in every non-war year between 1938 and 1999. Something that’s was pretty damn ubiquitous throughout TV’s formative years in general. Indeed, for a spell in the late 1950s, it had become so omnipresent the evening BBC News bulletin was usually billed as News and Cricket Scores during the summer months.

Admittedly, when it comes to that overall ‘episode’ count, it doesn’t hurt that given the long-winded nature of the sport, TV coverage of cricket often required dipping in and out of action to make room for other programmes. But hey, it’s billings we’re counting here, and billings are something cricket generates in spades. Or unusually wide cricket bats.

Anyway, and this won’t be much of a surprise given the popularity of Test Match Special on The Light Programme and Radios Two through Five, cricket first became a broadcasting fixture on the radio1. At a very early stage in the medium’s life, in fact; the first broadcast instances coming in 1923, starting with Men’s Talk: Cricket, by “Mr F.B. Wilson” (most likely Frederic “Freddy” Bonhôte Wilson, a keen batsman and cricket captain for Cambridge University, later sports journalist of high regard) airing on 2LO London at 9.55pm on Thursday 17 May. A mere ten minute natter about the sport it may have been, but the tap had been turned on.

[*UPDATE: Thanks to Guy Barry for writing in with the following (thanks Guy!):

TMS has been on several different networks but not normally, as far as I’m aware, Radio 2. (A check on Programme Index reveals two half-hour broadcasts in 1981, and that’s it.) It would take too long to go through all the various changes in detail but its main homes have been the Light Programme, Network Three, Radio 3 medium wave, the old Radio 5, Radio 3 FM, Radio 4 long wave and Radio 5 Sports Extra (with occasional outings on Radio 5 Live).

Incidentally the last-ever broadcast of TMS on analogue radio was in July this year – separate content on Radio 4 LW is being discontinued next March, in advance of the transmitters being switched off completely. From next year TMS will be a digital-only broadcast on Radio 5 Sports Extra. END OF UPDATE]

2ZY Manchester aired Talk on Cricket, by John Molyneux on 26 May that year, with 25 whole minutes to play with, while the following spring saw a whole (if generally untitled) series looking at the sport in more depth (“No. 4: J.W. Cameron, M.A. on fielding” etc). As far as concentrated cricket programming went, the first regular strands were born in Scotland, with Cricket Corner (hosted by Mr C. H. Webster) starting in June 1925 on 2BD Aberdeen and airing each Friday evening, and Cricket Talk airing on 5SC Glasgow from August of the same year.

Save for the curiously-titled programmes like Around the Clubs – Local Cricket Prospects going out on 5SX Swansea, or Mr John Fleming: Some Cricket Prospects on 2BE Belfast, both in April 1926, it does appear much talk was of the game in general, rather than any specific updates on the sport, and certainly no live match coverage. Curious-sounding outliers like The Annual Ball of the Swansea Football and Cricket Club, Relayed from the Patti Pavilion were more common, in fact.

The changed on 7 May 1927, with 2LO broadcasting the very-much-as-it-says-on-the-tin The Start of Cricket, offering the first day’s play from the Oval between Surrey and Hampshire. The Radio Times of the day billed it thusly:

“This evening all of them who could not enjoy the match from under the shadow of the historic gas-works will be able to hear it described by one of the most famous of living cricketers, who is also one of the most expert critics of the game.”

The expert mouth delivering those descriptions belonged to Middlesex and England batsman Pelham “Plum” Warner, one of just two people to be awarded Wisden Cricketer of the Year on two occasions (1904 and 1921, if you were wondering).

Once the live coverage of batting had opening, it didn’t take long for the first international cricket match to feature on 2LO – a whole week in fact, with Essex versus New Zealand going out on 14 May 1927. To mark the coverage, Stacy Aumonier penned an article for the Radio Times, and following a story about explaining the rules of cricket to an American (“It is a joy for ever to me to know that he went back to the United States thoroughly convinced that cricket was a far more exciting game than baseball!”), he muses on what took so long.

However, the point is that cricket may be and often is the most thrilling game in the world, and the recollection of that afternoon came back to me just now as I was pondering the question of the broadcasting of cricket. There is no question but that the broadcasting of other sports – football, racing, and the Boat Race, etc. – has been among the most successful efforts of the BBC, and it follows therefore that the national game cannot possibly be ignored. I was ill in bed when England played Scotland at Rugger a few months ago, but I listened, and although I don’t understand the game (we played Soccer at my school), I was nearly sick with excitement! But imagine a cricket match towards the end of the season, with perhaps the championship depending on the result – say Yorkshire and Surrey at the Oval. The last day, a sticky wicket, Surrey with eight wickets to fall, wanting one hundred and thirty-seven runs to win. What a chance for the commentators!

(…)

And at that point old ladies in the Midlands (who have never seen cricket played) begin to die of heart-disease from sheet excitement. There is the sound of the Commentator drinking something out of a flask. We all begin to wish it was all over, or that broadcasting had never been invented, or that we were there, or – What a game!

The Most Thrilling Game in the World, by Stacy Aumonier, Radio Times Issue 188, May 1927.

Ten years hence, live commentary on cricket matches had become both popular and commonplace on the wireless, though any related increased death rate of old ladies in the Midlands region remains unrecorded. However, now there was a new game in town: radio with pictures (i.e. telly).

It only took until 24 June 1938 for the BBC’s Outside Broadcast team to experiment with live coverage of the sport, that initial attempt picking a suitably major occasion: The Ashes at Lord’s (sadly, a week not yet included in Genome). Denis Compton and Hedley Verity featured for England, while Bradman and ‘Tiger’ O’Reilly starred for the Aussies. A big occasion for England’s national sport, and one that would surely be shouted from the rooftops in the BBC’s official organ. Surely?

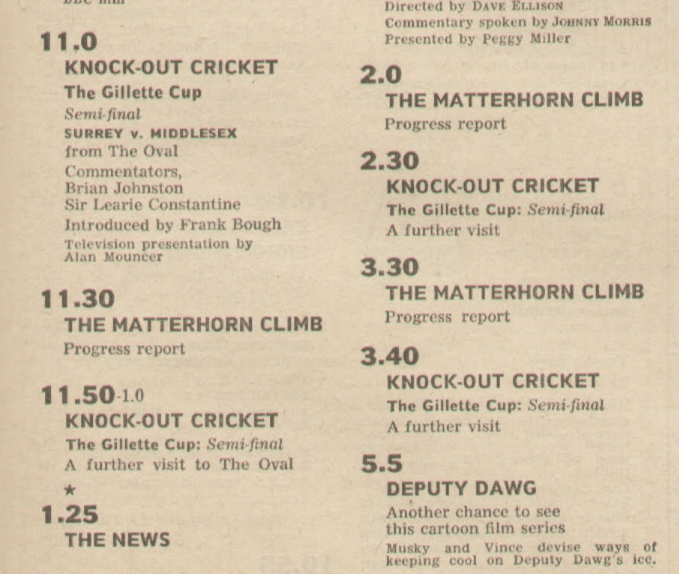

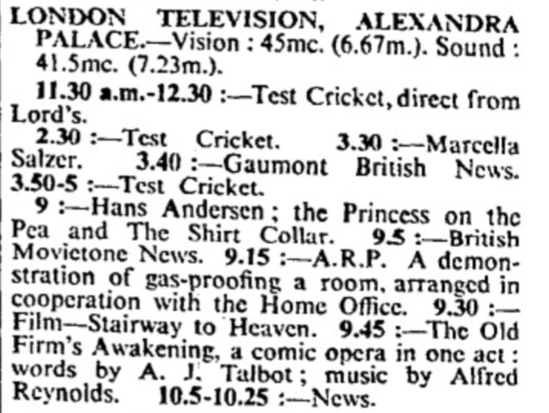

Ah, you know me too well. The Radio Times was reliably coquettish about the broadcasting breakthrough, relegating the coverage to some small print in the corner of a page, casually mentioning that “By kind permission of the MCC, the second Test match between England and Australia will be televised”.

The press were similarly coy about the coverage. The Daily Mirror’s TV listings for that day happily billed the match – broadcast for an hour at 11:30am, another hour at 2:30pm, and once more between 3:50 and 5pm – but accompanying copy regarding television was instead filled with breathless excitement at the BBC’s announcement of forthcoming footage from the India vs The World Polo match airing in a few weeks time.

The Telegraph were a little more excited about the breakthrough, with a statement that “more than three hours of play will be shown on the screen each day” and that “this is the first time that cricket has been televised”. If you’re thinking that’s hardly effusive, consider that The Times’ Broadcasting page merely mentioning that the match “will be described at intervals in the National and Regional [radio] programmes”, with reference to TV coverage only given to readers eagle-eyed enough to pick out the millimetres afforded the television schedule.

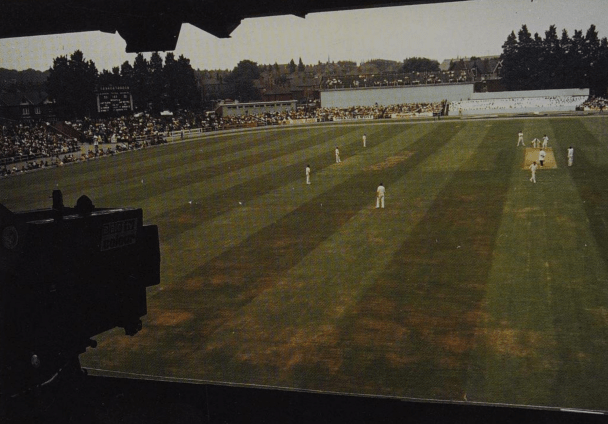

Fortunately those behind the cameras were taking things much more seriously. A lot of the work was carried out by Ian Orr-Ewing, having worked with the suits at Lord’s to procure permission for the match to be televised by a BBC Outside Broadcast team still getting used to broadcasting outside, where the action would be captured by three cameras, each mounted on a turret in a set up described by Orr-Ewing as “so much string and sealing wax”.

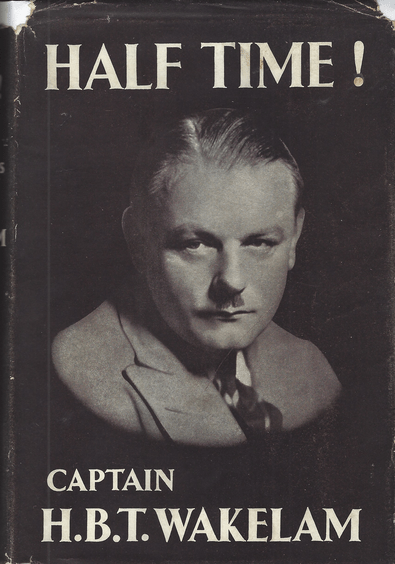

Commentary was provided by Captain Henry “Teddy” Wakelam, who generally operated as a rugby commentator (his 1927 comms for England v Wales at Twickenham comprising the first ever running sports commentary on British airwaves), but who was also skilled at lending his tones to other sports. Wakelam’s first foray into running commentary is worth mentioning here: as it had been a thing that simply hadn’t existed before he rolled up at Twickers that January morning in 1927, he’d been unsure how to play the whole thing. His producer Lance Sieveking had a plan in place for this – at the ground, he introduced Wakelam to a man from St Dunstan’s who’d be sitting next to him throughout the match. That man was blind, and Wakelam was tasked with describing the action to him, rather than the home audience. Thus, the long-standing commentary trick of ‘act as if you’re talking to one person rather than millions’ was born.

Before that first televised test match, Wakelam had mused on how styles of commentary style might need to be adapted for the new medium, in his autobiography Half Time: The Mike and Me (London Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd, 1938). His thinking was that, with live footage of the action being available, the commentator should become more of a compère than mere narrator of all that is happening, adding context where necessary, and not become a “mere talking machine who can tell a good story”.

Harking back to his first-ever radio commentary at Twickenham, on being initially asked to attempt the practice that had recently taken off in the USA, he penned the typically blustery statement “On the principle of ‘try anything once,’ and also with the confined conviction that if an American could do it I could, I agreed.”

With Wakelam on compère duties (history doesn’t seem to have recorded whether he wore a sparkly jacket), that inaugural broadcast was deemed a success. It certainly helped that the match was one where (to go by the match report from the following day’s Times) “the weather was delightful and the wicket true”, with England closing at 409 for 5, and batsman Wally Hammond grabbing an undefeated 210 (“one of the greatest innings of his career”). In fact, that opening broadcast went so well, permission was swiftly granted to allow an additional hour of broadcast at 6.15pm – though as no television was scheduled to be broadcast between 5pm and 9pm that day, it’s questionable how many viewers would have known to tune in for it.

The press were also enthused by the coverage, that weekend’s Sunday Times printing the following review:

The televising of Saturday’s play in the Test Match allowed viewers to see players more intimately than most of the spectators could have done (writes our Television Correspondent). The ball was clearly visible most of the time, particularly when close-ups were given of Bradman at the wicket. A clever piece of television technique was employed as Bradman hurried back to the pavilion, apparently unconcerned at having scored only eighteen. The applauding crowd was brought in as a background to the retreating Australian, Ames crouching down expectantly behind the wicket, Verity wetting his hands as he walked back with the ball, the way in which Bradman kept his eye on the ball until it met the bat – such details were clearly visible.

“Close-Ups” of Ball and Batsmen – Television Success, Sunday Times 26 June 1938

With the coverage widely accepted as a success, the only question that remained was: when could they do it again? This being the very early days of television meant that subsequent Test matches at Headingley and Old Trafford were out, as transmitters weren’t yet in place to beam footage back to London (which contained Britain’s entire TV audience at the time). Luckily, the fifth Test of the series was back in London, at the Oval, meaning London’s televiewers could enjoy more coverage of TV’s latest sport. As quite the treat it was, too – England won by an innings and 579 runs, with Leonard Hutton helping himself to a record-walloping 364 runs.

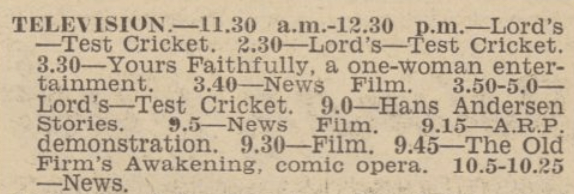

The following summer saw the BBC concentrate on improving their cricket coverage. The start of the first Test against the West Indies on 24 June 1939 saw coverage airing at 11.30am, 2.30pm, 3.50pm and 6pm, while on-topic light relief was offered by Charles Heslop starring in Reginald Arkell’s comedy play Percy Ponsonby Goes to the Test Match at 3.30pm. But this was no small undertaking. It was soon discovered that none of the gates in place at The Oval were large enough to admit the BBC’s Outside Broadcast van, meaning a team of workmen had to be hired the following month to construct a large gate for future broadcasts. Until that has been put in place, interim solutions such as knocking the roof off the van and deflating the tyres had proved fruitless, and instead a thousand feet of cable had to be laid from the OB van’s location outside the ground. Still, with the new gate in place, there’d surely be no interruption to future cricket coverage on the new Television Service. Hoora… sorry, World War What?

Following the war, the BBC Television Service would resume on 7 June 1946, and only a couple of weeks after that, cricket coverage resumed to lift the spirits of a battered Britain (or at least the bits of it that liked cricket). Lord’s was the location, and India were the opponents. That week’s Radio Times promised that “the television cameras will be exceptionally well-placed for the game”, and a full hour of extra evening coverage was promised each day at 5.30pm. Aiden Crawley was at the lip-mic, accompanied by Brian Johnston (at the start of a commentary career that would last for almost fifty years), the pair promoted by the RT as there to help viewers ‘follow the play’ rather than as mere commentators. Johnston later recalled his decision to move into the ‘play-follower’ box, pointing out that by that point, only four Tests had ever been televised, so the producers, commentators and cameramen were pretty much as new to the broadcasting experience as he was.

Cricket being cricket, and British summers being British summers, 1946 saw the first real instances of something that would become a hallmark of cricket coverage: filling the airtime with something, anything whenever rain stops play. This was a time long before the option of action replays, or even available footage of previous matches. Something needed to be done – as we all know, dead air is a crime – and Crawley and Johnston were the men to do it. Such as the time during the Oval Test of 1946, where viewers were promised ‘a surprise’ during a rain break as the camera slowly panned through the crowd to focus on “the Prime Minister”, who’d been enjoying the match with a small entourage, including “his wife, Mrs Churchill”. Except, of course, it being 1946 and the PM taking time away from Number 10 to attend the match was actually Clement Attlee, along with – crucially – his own wife, Violet Attlee. A correction was duly issued, albeit after the remark had been repeated, and there’s some proof for you that it’s probably better when sports presenters do know at least the basics of politics.

1947 brought a new foil for Johnston, in the name of Jim Swanton, at the time known for his work at the Telegraph and on the radio. On television, he would also go on to fill the role of prank-recipient at the hands of the mischievous Johnners. Such as the time when, on starting his summary of play, finding his braces grabbed and pulled by Johnston, and left to deliver a five-minute summary wondering if or when his cohort would let them snap back against his body.

Not that Swanton was the only stooge in the commentary booth. 1977 saw veteran Aussie mikesman Alan McGilvray feature in the radio commentary box for Test Match Special. During a brief lull in play, Johnston muted his mic and offered his cohort a large slice of sticky chocolate cake. McGilvray duly accepted, and took a generous mouthful, only to hear the words from next to him “that ball just goes off the edge and drops in front of first slip… let’s ask Alan McGilvray if he thought it was a catch.”

As the 1940s came to a close, live television broadcasts were still largely restricted to London-based grounds, but efforts were ongoing to make the most of the coverage. New camera angles were employed – such as positioning a camera to capture action behind the bowler’s arm, providing a much better view of deadly fast bowlers or devious spins. Johnston and Swanton had settled into a real double-act role, and cricket fans returning from work would ensure they’d tune into coverage just before the 6.35pm news, where Swanton’s colourful summaries of the day’s play beat newspaper reports to the punch by several hours. Swanton summarised his technique for a summary that didn’t have any defined duration – it had to start after the end of the final over and finish thirty seconds before 6.35pm prompt – taking the approach of pretending he was merely letting a friend know what they’d just missed. By all accounts, Swanton mastered this art to perfection – though one time the wild gesticulations of the floor manager that time was running out resulted into Jim snapping, whilst on-air, “WILL YOU KEEP STILL?”

1950 brought a new era in the BBC’s TV coverage of cricket, with the first journey outside the capital to broadcast a match, travelling all the way to… Old Trafford? Trent Bridge? Edgbaston? Well, the complexity involved in setting up camera positions meant that the sojourn into the provinces didn’t reach any further than Ilford for a three-day match between Essex and Warwickshire, with scaffolding erected to offer a slightly precarious home to BBC cameras and cameramen – an internal BBC report at the time noting how the operator of Camera One had to move with special care, what with him standing on the edge of a sheer drop.

With coverage completed from Essex, the next trip was north to Trend Bridge for the third Test, marking the most northerly point a live BBC TV Outside Broadcast had been made at the time. The choice of camera positions allowed for a lens to be trained on West Indies spinner Sonny Ramadhin’s bowling hand, giving viewers an inside track on what England’s batters were facing – an innovation that lacked the close-up finesse one might have nowadays, but which generated gushing column inches in the press of the day.

July 1951 saw another landmark moment, with a women’s Test match between England and Australia getting live coverage throughout the day on a Saturday, Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. On top of that, the match commentary team was led by Marjorie Pollard, former England hockey international turned cricketer and founder member of the Women’s Cricket Association. The experience wasn’t entirely new for Pollard – she’d first provided radio commentary for a men’s cricket match in 1935 – and she was perfectly clear about her preferred audio-only role, announcing “I’m no glamour girl and I don’t want to face that dreadful TV instrument”.

The construction of a new transmitter at Holme Moss outside Manchester meant that in 1952 cricket’s TV footprint could finally include Old Trafford and Headingley, meaning the BBC could now broadcast pictures from all five Test match grounds. With that year’s Test match visitors being India, an internal BBC memo from veteran radio commentator Rex Alston provided a guide to pronouncing the names of visiting players correctly. Not that Test debutant Fred Trueman was in anywhere near as welcoming a mood, taking three of the first four Indian wickets without a run being scored. The second Test was the commentary box debut of Peter West, a name that would become familiar to TV spectators over the next few decades.

The range of locations from which cricket could be broadcast continued to grow, so much so that provincial regions could now be expected to provide coverage of matches. If STANDARDS were to be maintained, however, guidelines had to be laid down. And laid down they were, with producer Antony Craxton putting out an internal memo on How Things Should Be Done:

Unlike some sports which we cover, cricket on television is, in my opinion, second best to being on the ground. Only one reason is needed to prove this in that it is just not possible to follow the ball often enough, and thus wickets fall unseen. It is therefore most important that the producer of televised cricket should have a pliable plan in his mind as to how best and how faithfully he can reproduce cricket on the screen, realizing that all the action cannot be covered. Above all, he must have a wide knowledge of the game, not only so he can anticipate as far as is possible events on the field, but also to guide his commentators along the best lines of thought.

Then, of course, he ought to be an enthusiastic cricket watcher or player, for any slight relaxation on his part may: result in the missing of a vital catch or an important incident. He must in fact not get bored or feel that cricket produces itself, as has been suggested. There is no doubt that an enthusiastic producer can make a rather dull game into enthralling viewing by clever use of his cameras – not only on the field of play. He must, however, not fall into the major trap of distracting the viewer with off-the-field close-ups at tense moments in the game when all the attention is demanded on the actual play.

Antony Craxton, Internal BBC Memo, 1952

Craxton’s dedication to the art extended as far as setting out preferred positions for cameras around any cricket ground, and what they should capture. He also expressed opinions on how commentary should be handled, recommending that commentary during weekday working hours be a bit more descriptive, as the cricket hardcore are less likely to make up the bulk of the audience. Okay, he said at that time of day the audience were “predominantly of the female sex, and I feel they would prefer more commentary”, but at if nothing else he was at least conscious of the time of day each broadcast aired, and considered how best to meet the needs of that audience.

One major problem encountered by cricket coverage was that the bulk of live coverage came during weekday working hours. Outside of those hours – especially in the period where BBC2 didn’t yet exist to offer an alternative channel – there was a lot more competition. Much of the 1950s saw internal conflict at the Beeb between the Children’s Television department who’d want to keep a place for their programming each day, and the Sports department who’d quite like it to move out of the way in case an important wicket was missed. The sports department went as far as offering commentary adapted for children on Test match days if the Children’s department would surrender half of Children’s Hour to cricket coverage. But, unsurprisingly, no dice. Joanna Spicer, Head of Programme Planning put out a BBC memo in 1957 stating that “while Brian Johnston is more than capable of adjusting his commentary to children, other announcers would not be so good at it.”

This would be a longstanding issue until the arrival of BBC-2 in 1964, where at least the two could peacefully co-exist. Well, aside from any bickering over who got the top bunk of BBC-1, anyway.

By the late 1950s, BBC-tv schedulers decided that the general audience might prefer to see other programmes at the close of cricketing action, but Swanson was understandably less than keen on the plan. As a result, he wrote to Head of Outside Broadcasts Peter Dimmock (a regular name in this rundown), pointing out the sacks of mail his summaries generated from a grateful audience. This was backed up by an internal memo from BBC Sports Organiser Jack Oaten, who believed the summaries to be “of greater importance as a service to the viewer than a good deal of the play earlier in the day”. As a result of this campaign, the summaries survived. At least for the time being.

The hip and swinging sixties saw further changes to the way cricket was covered on the BBC. 1963 saw the introduction of one-day cricket, which ushered in a new sense of immediacy to the sport (well, in the sense that taking a whole day to play a match is better than it taking several), and with such changes afoot some of the old voices behind the coverage such as Johnston and Swanton were nudged out of the TV commentary box in favour of former cricketers.

The start of the end for Johnners et al came during the final Test of the 1961 series between England and Australia. As the final match at the Oval meandered towards a draw, Johnston and guest co-commentator Jack Fingleton passed their time sharing gags, quips and anecdotes, along with musings on the wife of scorer Roy Webber. Head of Outside Broadcasts Peter Dimmock was far from amused, and neither were a number of viewers, who wrote to the broadcaster to complain. Within a few years, Johnston made the switch to radio commentary, his whimsical musings feeling much more at home. In his autobiography (It’s Been a Lot of Fun), Johnston mused that “I’ve always maintained that a TV commentator can never hope to please everybody any of the time. He will also be extremely lucky if he can please anybody all the time.”

1964 saw the arrival in the TV commentary box of Richie Benaud, who’d been a part of the Australian team a few years earlier while Johnston and Fingleton controversially waxed jocular. Already familiar with sharing his views in print and broadcast media, he proved a popular addition. This was no coincidence. Whilst still a player, Benaud attended a three week BBC course on covering sport instead of travelling with the rest of his team to Asia, and would routinely appear at the back of commentary boxes to observe the craft at close quarters. By 1960, he was providing occasional radio commentary for the BBC, before becoming a full-time cricket journalist and commentator following the end of his playing career.

Benaud’s sense of preparation went as far as putting together a list of phrases to avoid at all costs, including cliches such as “at this point in time”, “I really must say”, “Of course”, and “to be perfectly honest”. Filler phrases all, that add nothing to the illumination of the viewer, with Benaud keen to avoid talking down to viewers. This thoughtful approach would later be underlined to commentary teams by Controller of Sport Jonathan Martin, who would point out that the Titanic was a tragedy, the Ethiopian drought was a disaster, so a mere dropped catch in a Test match should never be deemed a suitable cause for either word.

1964 saw another major change for cricket on the BBC. Namely, the introduction of BBC2. This afforded an extra hour of cricket coverage each evening without the need to trample over children’s programming. Similarly, several uninterrupted hours of coverage could be screened on Sundays without needing to break for mandatory religious programming, starting in May 1965 with the first edition of Sunday Cricket, a series of matches played under knock-out rules, starting with the spectacularly-named International Cavaliers XI taking on a Worcestershire XI. This could run from 2pm to 6.30pm, with only occasional intervals, making a treat for cricket fans lucky enough to own 625-line sets and live in a region that received the new channel.

As Johnston started his migration back to radio, John Arlott made the move in the opposite direction. Another radio commentator of the highest regard, Arlott moved to television for occasional Test matches and would become part of the main commentary team for the Sunday Cricket coverage. However, Arlott’s florid commentary style never felt like a suitable accompaniment to television pictures, and he would move back to radio where this true stengths lay. For both Arlott and Johnston, it’s probably fair to say this was no demotion. Cricket enjoys a rare reputation for being a sport a lot of people prefer to experience over the radio airwaves, especially at a time when TV coverage needed to dip in and out of matches to make way for Watch With Mother or the news.

A more successful – if eccentric – addition to the TV commentary team was former England captain Ted Dexter, whose voice was heard on BBC Television for the first time in 1968. After reducing the amount of time spent at the crease, he’d initially moved into the world of business, as well as dipping his toe into politics, contesting Jim Callaghan’s Cardiff South East seat on behalf of the Conservatives in 1964. For the BBC, he’d take on the role of summariser, taking in a few Test matches each summer, and his association with the Beeb would last over twenty years, despite his other interests. One of which was racing. So much so he’d bring his own portable TV to the ground, so he could keep one eye on the latest action. This proved a boon on an occasion at Canterbury when a power failure caused the BBC’s monitors to fail. Dexter offered up his own screen as a workaround, and the broadcast was able to continue.

Not that electricity was always his friend. On one occasion at Edgbaston, rain had stopped play during a test match. On chatting to Peter West atop the pavilion roof – both holding umbrellas to compensate for lack of shelter – dark storm clouds gathered overhead. As Dexter recalls, “We were just going into the interview and felt a crunch and a jolt in my arm. I said: ‘Peter, I think I’ve been struck by lightning.’ He said: ‘Never mind that, what about Boycott’s innings?’.”

By 1969, the lush greens and cricket, erm, whites could be enjoyed in full colour on the BBC, and a fresh approach was brought to TV coverage. The unflappable Peter West stepped away from the commentary box to became cricket’s first anchorman, a role he would enjoy for the next eighteen years. Former spin rivals Richie Benaud and Jim Laker were now first choice for the commentary box, the latter having moved from ITV in 1968. Ted Bexter and Colin Milburn (and, for a spell, Denis Compton) alternated as summarisers.

In addition to the live cricket coverage the BBC had so rightly been lauded for, highlight programmes were now a feature of the TV schedules. Previously, highlights had been restricted to the closing moments of live coverage, but now they were found to be suitable filling for a Twenty-Four Hours/Late Night News sandwich. With the holy quadrinity of West, Dexter, Laker and Benaud in situ, BBC TV’s cricket team were well equipped to see out the 1970s, able to remain unfazed at the rise of streaking at cricket matches.

The 1980s saw a new spark of popularity for the sport, a particular jolt coming in the 1981 Ashes series, with an unstoppable Ian Botham being the difference between the two sides. Tom Graveney had been added to the commentary line-up following a 1979 appearance as summariser, a stint that would last for fourteen years.

Graveney, a flamboyant batsman who often found himself out of favour by selectors in favour of more workmanlike players, had the humility to dip into his own catalogue of mistakes when passing comment on others. He was far from immune at making occasional gaffes during commentary either – an inadvertent comment about Curtley Amrbose’s bowling style included a remark that “the big fella can get it up any time he likes”, generating a swarm of letters from the amused and the affronted.

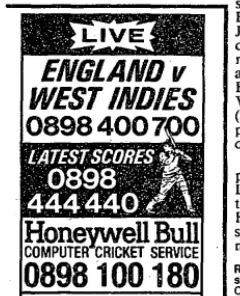

With this being the BBC in the 1980s, it shouldn’t be too surprising that the use of computers was introduced around this time, albeit from a slightly unlikely source. While the Beeb’s main computer evangelist Ian McNaught-Davis was promoting all things micro-based as part of the BBC’s Computer Literacy Project, it was Ted Dexter who was determined to introduce a tech-based solution. His goal was for a computer program to store reams of cricket-based info in a database. Dexter’s business connections let him spread the word around the UK’s tech industry, with the UK arm of American outfit Honeywell expressing an interest. As a result, the Beeb’s old system of expressing the score – physical letters and numbers moved into position on a magnetic board that was duly chromakeyed onto the screen – was replaced with a computer-based equivalent. This, along with Dexter’s database, meant much more relevant information could be thrown on screen in a fraction of the time.

Further innovations came about as the decade progressed. One major change was the use of double-ended coverage. Previously, one fixed camera would be used for the main angle, so at some points action would be viewed behinds the batsman, at other times behind the bowler, the former coming with the risk of action being obscured by the umpire. With double-ended coverage – an innovation first used by Australia’s Nine network – the view could remain behind the bowler, no matter which side of the field they’re bowling from. Similarly, an in-stump camera was employed, another idea first used by Nine. A clever bit of trickery involving a camera around the size of end-to-end packs of Polos placed inside the middle-stump, with a mirror angled to capture action from between the batter’s legs.

As the digital age of broadcasting beckoned in the 1990s – at which point an arms race between BBC and Sky was in place over sports coverage, super slo-mo cameras were deployed, offering a forensic view of action, especially in the event of contentious calls by the umpire. The rise of technological innovation in broadcast even led the ECB to request the BBC’s help in introducing the third umpire. This proto-VAR system was first used in 1992 for the South Africa versus India series, where Karl Liebenberg adopted the third umpire role, using TV replays to aid on-field umpire Cyril Mitchley regarding a run-out decision that saw Sachin Tendulkar dismissed. Television had now become a part of cricket to an extent that would have seemed unimaginable just a few decades earlier.

The BBC was at the top of its game by the late 1990s, but when you’re at the top, everyone wants to knock you down. Not only was subscription-based TV a challenger to the BBC Sport’s coverage – top-flight football had long fallen into the clutches of Sky – but a sport like cricket, with it’s well-to-do audience and break-heavy nature was pure catnip to commercially-funded broadcasters.

And so, in October 1998 – just over sixty years from BBC-tv’s inaugural cricket coverage – came the announcement that Channel Four had secured the live rights to most England home Test matches, with Sky Sports owning exclusive rights to the remainder. That meant £103m pouring into the ECB coffers, and the BBC left with just the rights to radio coverage. Accompanying the TV rights over to Four was the BBC’s voice of cricket for 35 years, Richie Benaud. The silver-voiced Australian would be sticking at the Beeb for their World Cup coverage, but then he’d be making the move to the commercial broadcaster.

And so, with live coverage of the 1999 Cricket World Cup, live TV cricket coverage on the BBC bowed out for a couple of decades. The rights to all live matches within the UK would become exclusive to Sky Sports from 2005, and a year later highlights of England home matches moved to Channel 5. It took until the 2006 Ashes before late-night cricketing highlights reappeared on the BBC.

In 2010, even ITV started riffing on the BBC’s pain by securing live rights to the new Indian Premier League, before adding 2010/11 Ashes highlights to their line-up.

At one point, BBC Studios-owned digital channel Dave had more live cricket rights than the BBC proper come 2016, when it procured live rights to show live coverage of the Caribbean Premier League.

Luckily, even when it comes to high-level live sports rights, what goes around comes around, and in 2020 live cricket coverage finally returned to the BBC. The ECB’s decision to ensure both subscription and free-to-air TV had a share of the pie meant the BBC finally recovered some live rights, and as a result – starting with England’s T20 match against Pakistan on 30 August. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given free-to-air coverage and lockdown preventing a live crowd, the coverage was a ratings hit, the daytime BBC coverage attracting 1.7m viewers compared to Sky Sport’s average of 331,000.

Luckily, for anyone who likes a sense of closure, live cricket is (at the time of writing) once more a fixture on BBC television (and, as programme trails inevitably add, iPlayer). Since 2020 both Men’s and Women’s matches in T20 and The Hundred have been broadcast live on BBCs One and Two, while highlights of One Day Internationals and The Ashes have enjoyed a place on primetime BBC Two.

And long may it continue. Sky may have deep pockets, but money can’t buy history, and the BBC has that in spades. Or unusually wide cricket bats.

EXTRA BONUS CONTENT: With huge thanks to the ever-splendid Paul R Jackson for providing me with a comprehensive list of names throughout the BBC’s cricketing history. Which is handy, because there was no way I could have included everyone in the write-up above. Over to you, Paul!

BBC TV CRICKET (List by Paul R Jackson, October 2023)

Presenters

Peter West 1968-86

Tony Lewis 1987-99 (Tests until 1998)

David Gower 1998

Isha Guha 2020-

Ebony Rainsford-Brent 2022

World Cup (1979; 1983; 1999)

Frank Bough 1979

Tony Lewis 1983; 1999

Peter West 1983

Tony Gubba 1983

Jonathan Agnew 1999

Steve Rider 1999

John Inverdale 1999

Dougie Donnelly 1999

Cavalier Matches (1966-68)

Frank Bough 1966-68

Peter West 1966

Sunday League Matches, BBC Two (1966 & 1969-89; 1993-?)

Corbet Woodall 1966

Frank Bough 1969-73

Peter West 1971

Mike Carey 1972

Peter Walker 1973-89

Gillette Cup

Mike Carey 1972

Benson & Hedges Cup

Peter Walker 1976

Commentators (with a tenure spanning three or more years)

Aidan Crawley 1939;1946-48

E.W. (Jim) Swanton 1946;1948-66

R.C. (Raymond) Robertson-Glasgow 1946;1948

Brian Johnston 1946-69

P.G.H. (Percy) Fender 1946-48

W.B.Franklin 1946-48

Robert Hudson 1947-64

Peter West 1947-86

Richie Benaud (Australia) 1964-70; 1972-99

John Arlott 1965-80

Neil Durden-Smith 1966-68

Jim Laker 1968-85

Peter Walker 1974-89

Christopher Martin-Jenkins 1981-86; 1988; 1995

Tony Lewis 1981; 1983; 1986-(94)

Ralph Dellor 1986-89; 1993

Ray Illingworth 1987-93

Jack Bannister 1988-99

David Gower 1994-99

Jonathan Agnew 1994; 1998-99; 2021-

Simon Mann 1999; 2022

Alison Mitchell 2020-

Isha Guha 2020-

Nick Bright 2021-

Summarisers (with a tenure spanning three or more years)

Jack Fingleton (Australia) 1956;1961

Denis Compton 1958-75

Richie Benaud (Australia) 1960; 1963

Colin Cowdrey 1963; 1969

Ted Dexter 1965; 1968-87

Geoffrey Boycott 1969; 1977-81; 1990-(99)

Ray Illlingworth 1975; 1984-93

Tony Greig 1975-76; 1983

Everton Weekes (West Indies) 1976; 1979

Ian Chappell (Australia) 1977; 1989; 1993; 1997

M.J.K (Mike) Smith 1978-81

Tom Graveney 1979-(93)

Peter Loader 1979; 1983

Ian Botham 1980-81; 1983; 1988

Tony Lewis 1981; 1985-86

Bob Willis 1982-83; 1985-87

Jack Bannister 1983-84; 1987

David Acfield 1987-89?

Mark Nicholas 1989; 1994

Simon Hughes 1992; 1994-99

David Gower 1993; 1998

Colin Croft (West Indies) 1995; 1999

Chris Broad 1995-99

Ravi Shastri (India) 1996; 1999

Dermot Reeve 1997; 1999

Phil Tufnell 2020-

Milestones:

24/6/38 1st televised Test match: England v Australia at Lord’s

27/4/69 1st televised Sunday league match: Middlesex v Yorkshire at Lord’s

30/8/98 Fourth days play England v Sri Lanka at the Oval, last test match coverage until 2020

30/8/20 1st live cricket on BBC since 1999 – T20 England v Pakistan, Emirates Old Trafford

Phew. That was quite a long one, wasn’t it? Next update soon: which might not be quite as lengthy.

5 responses to ““Bart, Elvis and The Baby” – The 5th Most Broadcast BBC Programme of All-Time”

John Arlott always used to do the commentary throughout the first team batting in the various incarnations of the Sunday League. After that he would leave the ground so he never saw the result.

LikeLike

Excellent article as always. (#6 on my list if anyone’s interested.) One small quibble:

“… given the popularity of Test Match Special on The Light Programme and Radios Two through Five… ”

TMS has been on several different networks but not normally, as far as I’m aware, Radio 2. (A check on Programme Index reveals two half-hour broadcasts in 1981, and that’s it.) It would take too long to go through all the various changes in detail but its main homes have been the Light Programme, Network Three, Radio 3 medium wave, the old Radio 5, Radio 3 FM, Radio 4 long wave and Radio 5 Sports Extra (with occasional outings on Radio 5 Live).

Incidentally the last-ever broadcast of TMS on analogue radio was in July this year – separate content on Radio 4 LW is being discontinued next March, in advance of the transmitters being switched off completely. From next year TMS will be a digital-only broadcast on Radio 5 Sports Extra.

LikeLike

Thanks for that Guy – I’ve added your comment into the body of the update as a comment, hope that’s okay! (I’m standing by counting the two 1981 outings for TMS on R2, as that’s the kind of scheduling quirk I always like to see, like the times ITV showed live Champions League football on the ITN News Channel because they didn’t have any other spare channels at the time.)

LikeLike

It’s conceivable that TMS was carried on R2 MW more often than that, or for longer. For technical reasons I won’t go into here, anything that appeared in a panel below the main Radio Times listings has been omitted from Genome/Programme Index, and that includes a lot of programmes during the 70s and 80s where there was a frequency split. I’m guessing that what may have happened here was that R3 MW was unable to carry TMS for some reason, so it was broadcast on R2 MW instead, and only the last half-hour got into the main listings since it was after 10pm when R2 lost its FM frequencies to R1. But without seeing a physical copy of the Radio Times it’s impossible to know.

It was certainly an unusual arrangement, whatever the reason.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kudos for the HMHB reference. Also the 1938 programme “A demonstration on how to gas-proof a room” puts the 1970s scary health and safety films into perspective.

LikeLike