Back again, finally. Following a programme where it was quite honestly a struggle finding a lot to write about (Bargain Hunt, in case you’ve forgotten) to one where I could’ve spent about sixty years writing about it. And did actually spend very nearly that long digging out a complete broadcast history, such is the way Radio Times covered Children’s BBC listings for much of the 80s and 90s. So, non-specific brand of sticky tape to hand, try not to burn your house down with your tinsel, wire hanger and lit candle advent crown, and settle down for…

6: Blue Peter

(Shown 5951 times, 1958-2021)

Okay, let’s get it all out of the way: here’s one I made earlier, sticky-back plastic, get down Shep, Richard Bacon’s nostrils, Joey Deacon, marvellous knockers, tedious edgelord stand-ups on clip shows pretending they laughed when the garden got vandalised, and an elephant doing a big ol’ poo on the studio floor. Me foot!

While it might not exactly have been Tiswas (indeed, on an episode of Room 101, Nick Hancock dismissed it as “Oh no! More school!”), there can be little argument that it’s a quintessentially British piece of kids’ TV that ultimately meant a lot to generations of children. Even if for many, the main thing that it meant was “What’s on Children’s ITV?”.

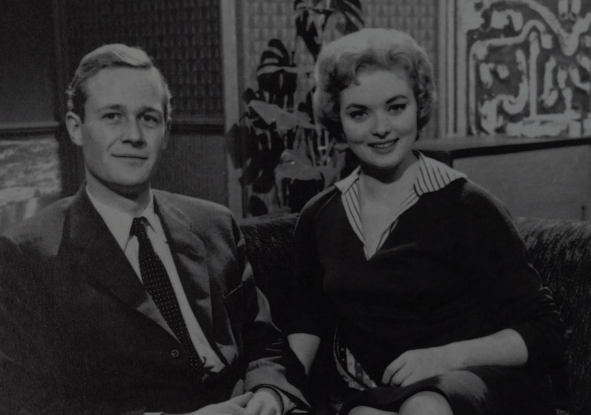

Everything was so different when Blue Peter was originally piped aboard the HMS Television in October 1958. Sandwiched between a mid-afternoon closedown (preceded by Quick and Easy Dressmaking: 1. Jacket with Hood) and “exciting film series about the Fifth US Cavalry” Boots and Saddles, S1E1 of Blue Peter arrived with the modest descriptor “Toys, model railways, games, stories, cartoons: A new weekly programme for Younger Viewers, with Christopher Trace and Leila Williams”. That seemed to be a lot to pack into the modest fifteen minute slot it was afforded.

A relatively common assumption seems to be that erstwhile BP editor Biddy Baxter created the series (Baxter herself begins her written history of the show dismissing that very notion), but at that time she was still busying herself producing sound effects for radio drama. The original producer of the programme was actually John Hunter Blair, who was given a mission by Head of Children’s Programmes Owen Reed to come up with a format designed to appeal to five- to eight-year-olds. That particular subset of inbetweenies were deemed too old to still be watching With Mother, but too young to find any appeal in proto-yoof magazine programme Studio E.

On paper, Hunter Blair seemed unsuited to coming up with such a format. Single and childless, the eccentric Hunter Blair preferred loftier pursuits such as composing operas and learning to speak various languages. However, he was armed with a wide range of knowledge on hobbies and interests that had entertained himself during childhood, and as an adult was keen to share his infectious enthusiasm with children. He had a particular affinity for model trains, to the extent that his office at the BBC hosted an intricate layout for his 00-gauge models, which he’d routinely play with while coming up with programme ideas.

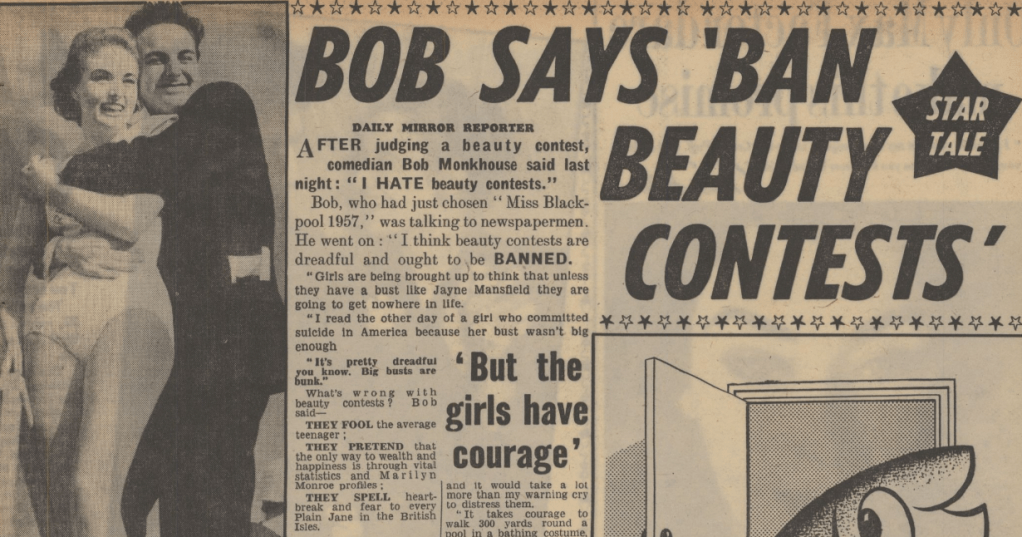

Hunter Blair’s fondness for all things Hornby certainly helped when it came to finding half of the original hosting duo. Actor Christopher Trace shared that enthusiasm, and spent the entire interview for the forthcoming hosting role playing model trains with his interviewer. The other hosting role was filled by Leila Williams, former Miss Great Britain, former host of Six-Five Special and who’d once taken advice from Frankie Vaughan to work on disguising her Staffordshire accent if she wanted to break into the world of showbiz. And who, going by the tabloids of 1959, once dumped Robin Day to start going out with Fred Mudd of the Muddlarks instead. Who she’d go on to marry, so fair enough.

For a title that would go on to (arguably) become more famous than any other in the history of British kids’ TV, the process of picking out the title ‘Blue Peter’ was similarly relaxed. As Biddy Baxter recounts the events in her book on the series (Blue Peter: The Inside Story), an early meeting between Leila, Chris and John included the editor musing that “Blue Peter would be a good name for the programme”. When asked by Leila what that title meant, John mused that “blue is a child’s favourite colour, isn’t it?”. What about ‘Peter’, asked Chris. “Peter is the name of a child’s friend, of course”, came the reply. Pub? Pub. It didn’t hurt that it happened to share the name of a flag raised by a ship before leaving port, tying in nicely with the programme’s quest to set sail on the sea of adventure.

Of course, all things in moderation. There was only a fifteen minute slot to fill, after all. And as such, the most action-packed part of early editions was the footage of a three-masted schooner running the titular flag up a pole in the title sequence. Once that starter was out of the way, a more sedate studio-based approach comprised the main course, often involving Leila playing with dolls and a besuited Chris mucking about with trains. Not the worst job in the world, of course, but not quite matching the vicarious glamour of Trace’s one-time role as stand-in for Charlton Heston in Ben Hur. Which isn’t a bad thing to have on your CV when you’re acting as surrogate Cool Older Brother to the nation’s children, of course.

Time would change that. Within a few years, the runtime extended from fifteen to twenty minutes, then twenty-five minutes (or occasionally longer if there was a sizeable gap in the schedule). The dolls and model trains were put back on the shelf, and livelier segments were brought in. On such occasion saw a lion cub brought into the studio, which turned out to be far less sedate than planned – the cub’s boisterousness causing lacerations on the arm of its handler while an unflappable Trace kept the interview under control.

While in Chris Trace and Leila Williams, the programme featured a pair of spritely young things, were in front of the camera, that wasn’t quite as true behind it. Showrunner John Hunter Blair suffered from a heart condition, and a couple of years into the show’s run that suffering increased, until one day he was no longer able to make it to his office-slash-playroom. While recuperating away from the BBC, a series of temporary producers stepped in, many armed with fresh ideas for the fledgling series. These weren’t always good ideas – the notion of having the programme alternate between “boy’s week” and “girl’s week” on a weekly basis – just ensured half the audience switched off each week.

Another grand folly led to the departure of original host Leila Williams, due to producer Clive Parkhurst basically failing to come up with anything for her to do. It wasn’t didn’t seem to be down to any lack of adaptability on Williams’ part – she’d proved perfectly adept at the role, and aside from BP was taking on small film roles and had recently featured in early ITV talent show Bid For Fame. And yet, Williams found herself dropped from several editions of the programme, before leaving on a permanent basis in November 1961. Not that this hampered Williams’ career entirely – she would go on to feature in several other programmes across ITV and BBC, such as hosting the BBC’s primetime vaudeville revival special Kindly Leave The Stage, and a judging role in excellently-named ice dancing competition Hot Ice and Cool Music, alongside a series of minor film roles.

By now, Blue Peter was suffering. Remaining host Chris was left to front the programme alone, and a queue of interim producers wasn’t going to improve the situation any time soon. With it eventually becoming clear Hunter Blair was unable to return to save the ailing programme, the call went out for a new permanent programme editor. And, to the surprise of many, the role was given to an aspiring young producer who a few years previously had been producing – yes! – sound effects for radio drama.

Biddy Baxter was tasked with transforming Blue Peter, but before that could begin she had to see out the remaining three months of her contract with BBC Radio, so experienced drama producer Leonard Chase was recruited to steady the ship for a spell. Immediately seeing the potential for improvement, Chase leant heavily on the factual aspect of the series, straying far from the original remit of “toys, model railways, games, stories, cartoons” and focused on a more wide-ranging view of what might interest the young audience. But there was still the problem of relying on Chris Trace to largely manage the on-camera action on his own.

The search for a new co-presenter was on. An audition was set up where each of four candidates would accompany Christopher Trace in reading a story, completing a Blue Peter make and interviewing a guest. The winning candidate turned out to be Anita West, actress, wife of Goon Show band leader Ray Ellington and mother to two young children. Her first appearance on the programme was alongside regular guest (and infrequent BP guest-presenter) Tony Hart, who would help settle her anxiety when carrying out her initial on-camera makes, until her confidence grew. It seemed sure that she would be a hit with the audience.

Sadly though, problems with her marriage led to a crisis of confidence – in an age where newspapers were fast becoming scandal sheets, any drops of blood in the water would surely have Fleet Street hacks sniffing around her private life. Despite that, West managed to keep her problems well away from her Blue Peter role, performing so well on screen she would soon be offered a full-time contract (a contrast from Leila Williams, who’d only ever been offered month-to-month contracts), along with the offer of working as an announcer at BBC-tv. The production team found themselves taken aback when the offer instead led to West offering her resignation, her tenure on the programme lasting just four months. A replacement co-presenter was needed, and quickly.

The problem was solved with the introduction of a dark-haired, serious and decidedly striking young new host. Valerie Singleton, had been another of the auditionees a few months earlier, losing out on the role to Anita West, but she immediately proved a more than capable presenter. Indeed, her straight-laced manner proved to be a key ingredient the programme had been missing. Her unflappable, authoritative and direct manner proved a suitable counterweight to Trace. Singleton was the cool teacher to complement Trace’s cool big brother mannerisms.

However, from October 1964 the programme began going out on Thursdays as well as Mondays, doubling the workload of the two-hander presenting team. As a result, with Trace pointing out that he as “bloody knackered” (presumably off-screen), a third member of the presenting line-up was added in 1966. Step forward John Noakes.

Trace was still very much the main man, however. The programme’s first two summer assignments – Norway in 1965, Singapore and Borneo in 1966 – focused on the former actor. However, with Trace suffering from vertigo, new boy Noakes soon became the designated action man for the series. Christopher Trace left the programme in 1967 (much to the dismay of Huw Wheldon, who reportedly – if incorrectly – exclaimed “there will be no Blue Peter without Christopher Trace”) to move behind the scenes at feature film production company Spectator. That move failed to work out, but Trace would subsequently make the move to reporting and presenting Nationwide amongst other gigs, plus he’d often take the time to phone the Blue Peter production office whenever he came up with a potential programme idea.

Trace’s departure led to more prominence for John Noakes. His role on the programme had come about almost by chance. Biddy Baxter was flicking through the local newspaper while visiting her parents in Leicester, and happened across a theatre review raving about local rep player Noakes, which mentioned his history working as an engineer on DC7s at BOAC. At ease in front of an audience? A day job that involved mucking about with very real aeroplanes? Someone certainly worth meeting in person, with the need for an addition to the BP hosting roster.

Not that there had just been a handful of candidates. On his arrival at TV Centre, Noakes was fiftieth in the queue to audition for the role. He was more than a little nervous, having only appeared on stage in character before, never having had to appear as himself, nor on national TV. On top of that, he was starting to feel disillusioned with the whole performing lark anyway. Despite all that, the nervous energy displayed by the then-31-year-old won over Baxter, and he was handed a three-month contract to join the series from late December 1965.

While history seems to have pegged him as the avuncular figure hosting Go With Noakes alongside canine companion Shep (as well as for breaking down when interviewed about Shep’s passing on BBC1’s teatime infoblast Fax! in the 1980s), his tenure was as action-packed as any in his thirteen years on the programme. Clambering up the mast of the HMS Ganges, setting a record for highest civilian free-fall parachute jump, clattering his way down the Cresta Run and (as pictured above) going full Fred Dibnah while climbing Nelson’s Column. He truly was the programme’s first true Man Of Action.

Noakes would be joined a few years later by Peter Purves, a one-time Doctor Who companion (Steven) who was subsequently too typecast to land any decent acting role after stepping out of the Tardis for the last time. His luck changed on being interviewed for the Blue Peter role, and it didn’t take long to decide he was the man for the job. Before he could get into the lift at Television Centre following his audition, Biddy Baxter and Rosemary Gill collared him and offered him the gig on the spot. He initially planned to stay for six months until more offers of acting roles reached his inbox. He ended up staying for almost thirteen years.

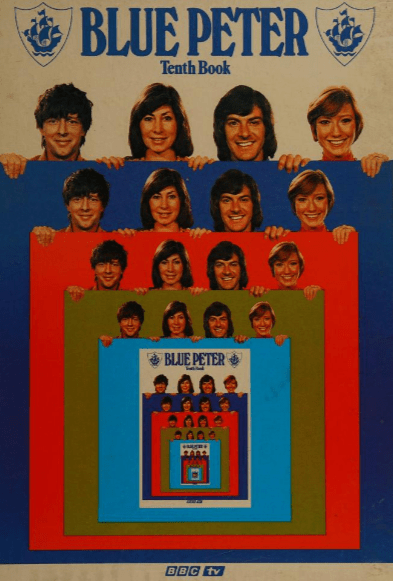

With the three saints of Peter on board from 16 November 1967, the programme’s first true imperial phase could begin. Little wonder that, in his marvellous book covering his personal history of the programme, future programme editor Richard Marson referred to the trio as “unquestionably the most famous presenting team in the show’s history”.

14 September 1970 saw another landmark in the history of the programme – the first ever colour edition of Blue Peter. That change could have come about even earlier – Monica Sims, then Head of Children’s Programmes, contacted BBC-1 Controller Paul Fox about getting some extra funds for the series so that the programme’s summer jaunt could be to somewhere a little more exotic than Cornwall, in keeping with the adventurous excursions from previous years, especially now there was the prospect of the film being broadcast in colour. Fox relented to be main request, but denied the request for the expense of shooting in colour. That decision led to disgruntlement from Fox in 1971, when repeated footage of 1969’s trip to Ceylon could only be broadcast in monochrome on the now multicoloured BBC1. The programme had more success with shooting in colour in May 1970, with director John Adcock being permitted to try out colour film for a trip aboard the QEII. That was just a test – the film itself was broadcast in black and white, but it proved that it could work, and that the programme could make the move into full colour.

However, the upgrade came with conditions attached. Only the larger studios within TVC were equipped to cope with broadcasting in colour, and those weren’t always available to the programme. Whenever circumstances dictated Blue Peter move into a smaller studio, it was accompanied by a move back into monochrome. This meant it took until June 1974 before the blues of ‘Peter could be enjoyed on colour receivers on a permanent basis. As a result, those with expensive tellies certainly got to enjoy a much more immersive experience with BP’s summer sojourns, starting with July 1970’s trip to a Mexico still buzzing with excitement from the previous month’s World Cup.

Another new introduction to the programme came about in March 1974, with the official unveiling of the Blue Peter Garden. Up until that point, the programme had been keen to utilise every spare bit of space in Television Centre, the big studio doors often being flung open to permit everything from vehicles to marching bands, but other programmes and occasions often called for use of that space, leaving Blue Peter locked indoors. BP often made use of the TVC car park, or the infamous TVC Doughnut, but those areas couldn’t be guaranteed to be available to a live programme. Far better to have a little bit of space that was very much the programme’s own safe space – specifically a secluded patch of land in front of the BBC restaurant block.

It had previously been pressed into use for programme segments in the past, but only really on an ad-hoc basis. Now, ‘inspired’ by their ITV rivals Magpie having their own smallholding at Teddington Lock, the patch of land was to become to sole preserve of Blue Peter. Now, tower block kids around the UK could be afforded their own surrogate set of flower beds, fish pond and – a little later – an Italian-style sunken garden.

As the programme prepared for the 1980s (aided by a new version of the theme tune composed by Mike Oldfield, above), a new presenting line-up evolved. As the new decade arrived, the team of Simon Groom, Tina Heath and Christopher Wenner didn’t quite enjoy the popularity of the familiar line-up of the previous decade (Lesley Judd having replaced Valerie Singleton in 1972 following the traditional presenter overlap), and the latter two-thirds of the team didn’t hang around for too long. Luckily, a much hardier troupe of presenters was about to provide a sense of solidity to the curved couch. Sarah Greene arrived in May 1980, while Peter Duncan joined the team that September. Each had previously appeared on screen in acting roles – Duncan in the likes of Space:1999 and Play for Today, Greene in ITV’s compelling housing association soap Together – but both slotted into their new presenter roles with ease.

It certainly helped that the series seemed keen to cover technological advancements of the 1980s, which was certainly a boon to any children-of-the-80s who’d pore over the electronic gizmo pages of their mum’s Kay’s Catalogue. Astonishing space-age achievements covered by the series included the first ever transmission of a fax message on British TV (sending a picture over the telephone line? Witchcraft, surely. If memory serves, it was a scribbled drawing of a brolly and some raindrops), plus a departing Tina Heath introducing viewers to the concept of ultrasound technology with a live broadcast of her baby scan.

1988 saw the end of an era for the series, with long-time programme editor Biddy Baxter leaving the series after more than 25 years at the tiller. Baxter wrote about the experience of finally letting go in the introduction to her own Blue Peter: The Inside Story book:

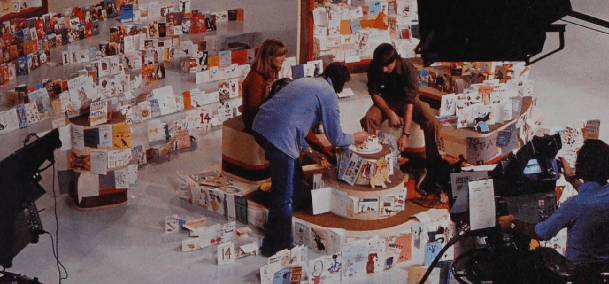

In the gallery, my stomach lurches — just as it had lurched every Monday and Thursday for twenty-six years. That special frisson peculiar to all live broadcasting when it’s the point of no return — no second chances or second thoughts. Will the presenters achieve that peak of perfection we’ve been striving for all day? Will the studio director make a particularly tricky effects sequence work? Will Rodney on Camera One be okay with that difficult tracking shot? He’s a genius, so if anyone can make it work, he will. BUT…

Considering that at least thirty people have the chance to make or break each live Blue Peter transmission, it’s amazing that the disasters are so few. Come the crunch, when it’s live there is that extra adrenalin flowing and an extra camaraderie that, nine times out of ten, creates pretty nearly what you’ve hoped to achieve. When the disasters happen they’re usually mega ones, like a telecine machine playing in an eight minute film breaking down at the beginning of the reel — on a day when there’s no back-up on video. Or a cheerful chap in a brown coat walking into the studio during transmission clutching a large black plastic sack and yelling: “Let’s be having you then, where’s your rubbish?” Or the anonymous engineer deep in the bowels of Television Centre pulling a vital plug that disconnects the large, motorised camera taking the most important shots in the whole programme.

But today the lurch was worse. It was my very last Blue Peter. ‘There was a large chunk of the programme completely unknown to me. I hadn’t written the script, I hadn’t even been allowed to see it. Lewis Bronze, Blue Peter’s talented assistant editor for the past five years, had been quite firm. “It’s your last programme and you’re going to be in it. Don’t worry, leave it all to me, just sit back and enjoy it!”

Biddy Baxter, Blue Peter: The Inside Story (Ringpress Books, 1989)

Ultimately, Bronze’s gambit certainly helped to quell any sadness on the part of Baxter as she prepared to leave the show. Any despair was swiftly reduced by the fear of appearing in front of Blue Peter cameras for the first time. By the end of the programme, she’d been coaxed down from the gallery, welcomed on-set, shown with a montage of programme highlights, given a large album of photos from her BBC career and presented with a prized a Gold Blue Peter Badge. The latter award was the very highest honour the programme would go on to bestow, putting Baxter in the same league as Paul McCartney, Steven Spielberg, Madonna, Sir David Attenborough and The actual Queen.

The late 80s and early 90s saw the programme start to make more of an effort to cover environmental issues – quite a change from those early years when anything emitting exciting plumes of diesel would have been deemed a suitably thrilling candidate for coverage. This period even saw the introduction of a green Blue Peter badge for environmentally-adjacent achievements.

From 1995, a third weekly edition of the programme was introduced, albeit a more fun~based edition of the programme airing in Fridays (usually between autumn and early spring months), concentrating more on things like celebrities than sea scouts. Whether the increased demands of an extra show were a factor or not (though by this point some episodes were pre-recorded), the turnover of team members increased during the 1990s. Though despite that, Konnie Huq (having joined in December 1997) would go on to become the third-longest serving BP presenter of all-time, clocking up just over ten years on the series. And, in fairness, it’s not as if presenters from the 1980s had a habit of hanging around for too long, as the following did-it-purely-because-I-could table of data shows:

Despite a revolving door of presenters during this spell, it wasn’t all grim during this spell for the series. It became one of the first BBC shows to land its own section of the bbc.co.uk website, and the programme warranted a pair of summer prom concerts. However, each spell of sunshine is followed by a little rain. Or, erm, snow. Yes, I do mean Richard Bacon getting the boot for being caught in the midst of nose candy. Don’t think that was mentioned in that year’s Blue Peter book.

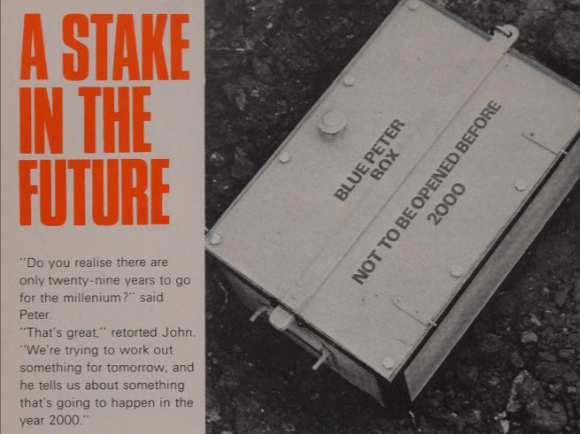

One of my favourite follies is the concept of the time capsule, and Blue Peter had been very much a part of this. The 1970s incarnation of the series had buried one back in the day, and with the arrival of space year 2000, it was time to dig it up. It must gave seemed such a distant future at the time, but in the event the BP Dream Team of Singleton, Noakes and Purves were still around to help dig it up. The fact the contents were in a worse condition than if they’d just bought each item off eBay only detracted from the achievement slightly. Honest. And it was fitting that the old team made a reappearance at the time, as with Konnie Huq, Simon Thomas and Matt Baker now on the sofa, the current generation of viewers has their very own stable team of presenters to call their own.

With Friday editions now commonplace, there was still a summer-sized gap in the programme’s broadcast calendar. That changed in 2001, when the addition of twice-weekly episodes during July and August saw the programming running throughout the year for the first time since 1965. The brand was extended further still following the arrival of Richard Marson as programme editor in 2003. With the something needed to fill the digital bits that made up the new CBBC channel, same week repeats of the regular Blue Peter show were joined in the schedule by spin-off series Blue Peter Unleashed from February 2002, that first episode promising “football with Steven Gerrard, speed boats, stuntmen, billiards and rock climbing”. That was joined later that year by Blue Peter Flies The World, which collected together trans-global reports from the programme.

As viewers gradually migrated to the new CBBC channel, viewing figures for the series on BBC One began to slide. By this point, a reduction in the programme’s budget had already seen it relocate to a smaller studio, and now it was being shimmied into a slightly less glamorous slot in the schedule – bumped back to 4:35pm from February 2008 to free up the post-Newsround slot for The Weakest Link.

A few years later, as 2012 drew to a close and with the UK’s digital switchover having completed in October of that year, it was decided that children’s programming no longer needed to be broadcast on BBC One. After all, any TV set now had access to the CBBC and CBeebies channels, meaning more room for programmes about buying houses and antiques on the Beeb’s flagship channel. And so, on Friday 30 November 2012, a regular episode of Blue Peter aired on BBC One for the last time. By this point, first run episodes of the programme were already going out on CBBC, so it’s hardly a surprise the berth on One was being given to something else. But at least that last regular appearance on the channel was something typically Blue Peter: as part of Children’s Commissioner’s Takeover Day, a quartet of competition winners were afforded the chance to produce the episode.

That wasn’t truly the end of the programme on ‘regular’ BBC channels, however. 20 October 2018 saw a BBC Two airing of Blue Peter’s Big Sixtieth Birthday, an hour-long special where former presenters returned to the studio to help the current team celebrate TV’s most storied children’s programme. Following that, occasional episodes of the series would get repeat broadcasts on BBC Two on Saturday mornings, though one suspects that was down more to needing something to fling into the schedule than anything else.

While the programme has – as one might expect – changed beyond all recognition during six-and-a-half decades on screen, so much so that it’s only been generating one episode per week since 2012, it’s comforting to know it’s still there. Even if at one stage, BBC Children’s Controller Richard Deverell decided that the programme should become “more like Top Gear”. Ew.

However, with the future of the CBBC channel in doubt – at the time of writing it’s due to be given the chop as a standalone channel (alongside BBC Four) in 2025, with all content becoming iPlayer-only from that point on. Will Blue Peter survive the cull? One can only hope, but even if it doesn’t, that’s one hell of an innings.

Phew, that was a long wait. Especially as I’ve hardly scratched the surface of the sixty-five years it’s been running for. Still, I’m sure the next entry on the list will be much easier to write about… oh. Sigh. See you soon!

7 responses to ““I Don’t Care Where That Tiger Cub Goes, Follow It!” – The 6th Most Broadcast BBC Programme of All-Time”

From my vague memory, the fax machine episode resulted in nothing being received in the studio. On the next episode it was revealed that one of the metal ramps (designed for cables to run under so that people did not trip over them) had cut through the wire connecting it to the phone line!

LikeLike

“Big busts are bunk”

LikeLike

Truly epic entry for a National Treasure. I feel like I’ve been holding my breath for that one ever since we got to the top 10 and now I can finally breathe.

The programme itself is so much more than the sum of its parts. It was often cringey to watch, with presenters doing the matey teacher act and guests looking paralysed with self conscious awkwardness. And yet, it’s in our collective psyche with its badges (always spoken of in bad impressions of Noakes’ North Yorkshire accent in my era), its odd things to make at home (I still have no idea what sticky back plastic is) and its animals.

It was sort of meta long before I knew what that was – quite happy to show viewers how it was being made while it was being made, to follow a presenter out of the studio into the scruffy innards of the BBC and the frank narration of how a presenter was feeling while they undertook some scary stunt out in the real world.

Most of all it was reassuring – a comfort blanket in a bewildering world as a kid. These were people who were always calm and who understood what was going on and so surely everything was going to be okay as long as they kept appearing, regular as clockwork, twice a week? Yes, there might be an oil tanker run aground or an inexplicable war in the Middle East or a hosepipe ban, but you can dream of having a dog like Shep and the world is safe again.

LikeLike

“I still have no idea what sticky back plastic is”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-adhesive_plastic_sheet

It was marketed in the UK under the brand name “Fablon”, although the company seems to have gone out of business. I think you can still buy it under other brand names.

You will find quite a number of sites claiming that “sticky-backed plastic” referred to Sellotape. This is entirely wrong, as Blue Peter referred to Sellotape as “sticky tape”. I pity all the viewers who were under the impression that they were supposed to stick Sellotape all over their finished creations!

LikeLike

For the record, Blue Peter was #9 on my list. Was it routinely transmitted in black and white as late as 1974? I ask because there was definitely a one-off black-and-white episode that year which has become rather notorious. This is from the lighting engineer Martin Kempton:

https://www.tvstudiohistory.co.uk/bbc-studios-in-london/lime-grove/

“Studio G [at Lime Grove] was used to cover for studios E and D respectively during 1970 when they were being colourised. After that, for a few years it didn’t actually close – it just gently faded away. For a while it was used occasionally as a training studio. It was then officially closed around 1972 although the equipment remained installed.

However, due to some industrial action at TVC affecting setting and striking scenery in that building it was coaxed back into action once again in 1974 for a Blue Peter. (This date has been confirmed by a sound assistant and cameraman who both worked on the show.) Apparently, towards the end of transmission a puff of smoke was seen in the apparatus room and the pictures went to black. The show ended with sound only and the studio was never used again. I remember exploring the deserted floor and the old control rooms in 1976 soon after first joining the Beeb and rather spooky it was too.”

LikeLike

Of course, Yvette Fielding has shed a slightly different light on Biddy Baxter in the last day or so, but tbh I don’t particularly think that makes Baxter’s tenure suddenly suspect – she was merely in the role far too long but was also obviously seen as a talisman (see also: Joh Nathan-Turner on Doctor Who, although that didn’t turn out nearly as well.)

LikeLike

[…] here’s a bit more bonus content from Paul R Jackson, with some added information on those Blue Peter reunions. Over to you, […]

LikeLike