What’s got eight legs, 22 balls and would kill you if it fell on you from a tree?

9: Snooker

(Shown 4882 times, 1937-2021)

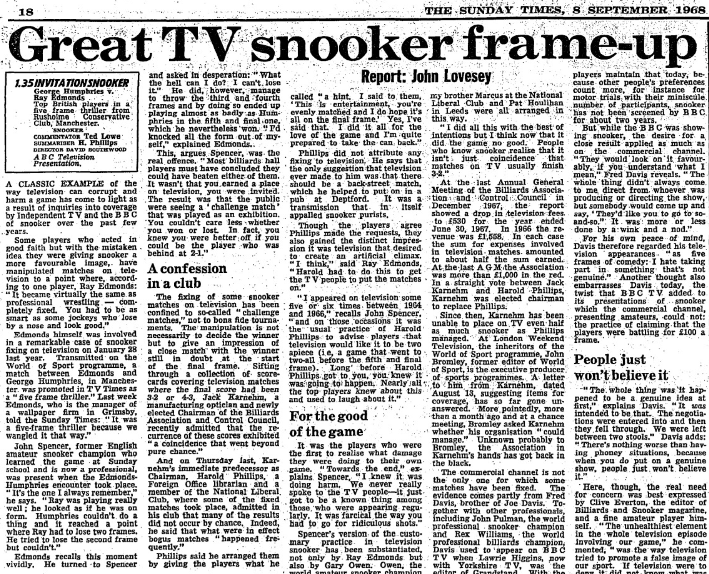

All together now: “For those watching in black and white, the pink’s behind the blue…”. Except, Whisperin’ Ted’s infamous line actually came from Pot Black, which is a distinctly different proposition to the next ‘programme’ on the list.

So: Snooker. Always a contender for the top ten, and perhaps a little surprising to see it as low as ninth.

With the sport lacking a unifying ‘Match of the Day‘-style branding, actual tournament play went out under the title of, well, ‘Snooker’ (or variants thereof), taking it into this top ten position. And that’s because, well, there’s been rather a lot of it on the BBC over the years. More of it than you could shake Len Ganley at. And it goes back a lot further than one might expect.

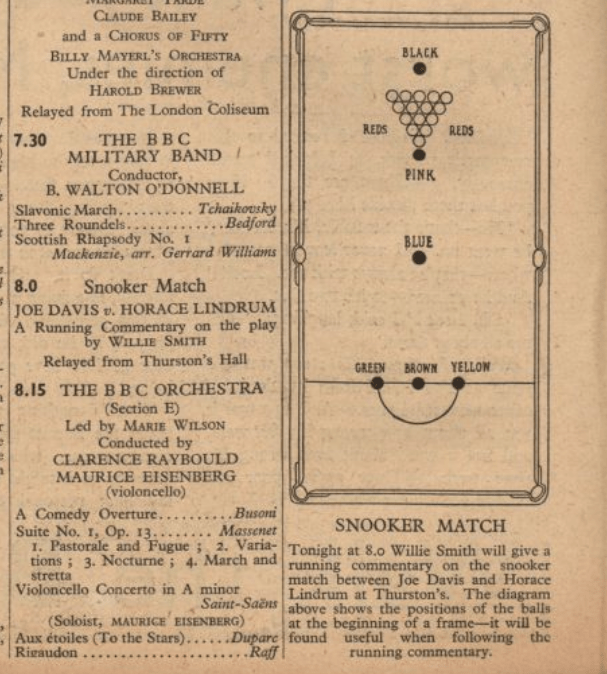

For a spectator sport where identifying colours such as yellow, green, brown, blue, pink and black is pretty darned integral, you’d reasonably expect it to only become a broadcasting event following the advent of colour television. Except, not only was it first broadcast long before BBC2 started pumping out colour programming, snooker was first beamed to the nation before television was a going concern. On Tuesday 10 December 1935, listeners to the London Regional Service were treated to fifteen minutes of commentary on a match-up between England’s Joe Davis, considered the world’s top player at the time, and Australian Horace Lindrum, then considered the globe’s secondmost snookersmith. As if to underline the challenge of describing the action to an audience who’d largely never seen a snooker table in their lives, the Radio Times printed one alongside that day’s radio listings.

How practical that miserly fifteen minutes may have proved is up for debate, of course. Snooker finals are hardly short affairs in this day and age – for example, the 2023 World Championship final between Luca Brecel and Mark Selby was a best of 35 frames. And that’s a brief clatter around a youth club table compared to this match, a prize match to settle a £100-per-man wager, based on two lots of 61 frames. The following day’s Daily Mirror reported that that day’s session had seen Lindrum come back from 10-5 down at the start of the afternoon’s play to draw level on ten frames all, with an aggregate points total of Davis’ 5,223 versus Lindrum’s 5,244.

The report also included mention of the match’s status as broadcasting first, relating how commentator Willie Smith (himself a billiards champion who’d turned his hand to the increasingly lucrative snooker) told of missed sitters (causing “expressions of amazement from spectators”) during that inaugural summary. That match between the two would go on for several more days – at one point breaking so that cheques for £650 could be awarded to Chelsea footballers George Mills and Harold Miller before play continued – only to end with Joe Davis winning by 32 frames to 29, ending the series at one match apiece, and subsequently nullifying the bet. In short: a lot of snooker, then nobody won.

Of course, that fifteen-minute fix of audio green baize action would be all that radio listeners received from that particular match, but Willie Smith was back on the lip-mic the following February for the rematch. This time, a generous 25 minutes were given to the coverage, which was won (along with the £200 kitty) by Davis. Moreover, snooker had begun to thrill the nation. And put paid to any claim from DLT that he invented Snooker On The Radio.

11 April 1936 saw live coverage from Dublin of a match between Seamus Fleming and W Lowe, as snooker began to grow in popularity in the Irish Free State, while the end of that month saw running commentary from the final of that year’s British Championship, where… Joe Davis beat Horace Lindrum. Again. Another sporting first occurred during sports roundup Saturday Contrast in December, with live coverage of Women’s World Snooker Champion Ruth Harrison as she took on Women’s World Billiards Champion Joyce Gardener, albeit in the discipline of billiards, with a ‘substantial prize’ on offer to the victor.

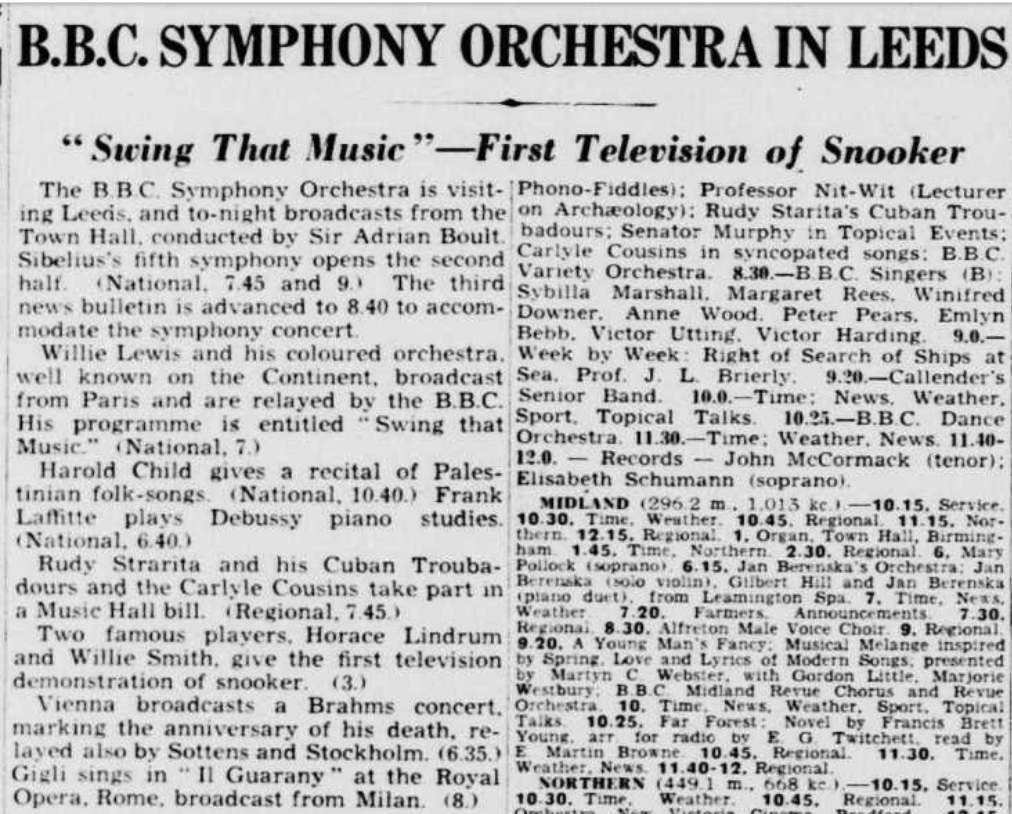

By now, television was on the scene, and surely snooker was a prime sporting candidate for the new medium. Admittedly, visual coverage of the sport would lack the verbal colour of radio commentary, but it would be so much easier to see what was going on, and unlike with many sports, a single fixed camera could be employed to relay the action. And so, on 14 April 1937, snooker was introduced to the television audience for the first time, with an offering billed as An Exhibition of Play by Horace Lindrum and Willie Smith.

Even more excitingly for readers of the Daily Telegraph on the morning of broadcast, there was the implication the event would include full orchestral accompaniment:

Luckily that week’s Radio Times went into more detail. The article explained how, from the early 1930s, snooker had gone from a distraction adopted by billiards professionals once they’d got a bit bored with their day job, to a sport that had overtaken its sister game in popularity. Initially, the announcement that a session of billiards was to be followed by some frames of snooker would result in half the audience suddenly realising they’d left the gas on and would leave the exhibition hall.

But, slowly but surely, billiards’ multiball cousin attracted more of an audience. 1933 saw the first national competition, a handicapped event open to amateur players around the UK. Much to the surprise of the organisers, around five thousand applications poured through the letterbox. Probably going to need a bigger hall, then. And yet, professional cuesmiths preferred to stick to billiards, only occasionally racking up the reds, meaning the growth in participants failed to result in much mainstream attention. Until the arrival on these shores of charismatic Canadian Conrad Stanbury.

While not quite as adept at the sport as homegrown players like Joe Davis, Stanbury added a sense of style, humour and colour to the sport, a stark contrast to the relatively austere Brits. Fellow Canadian Clare O’Donnell also arrived in the UK, taking on well-known billiard pros at snooker, his quick-fire approach to play attracting even more interest in the sport. While the style of the North American duo attracted attention, it was the arrival of Australia’s Horace Lindrum that provided a true rival to top British player Joe Davis. The matches between the two being broadcast over the radio proved how the sport was becoming more popular, and by 1937 former billiards pros were spending more time playing snooker than its parent sport.

In a passage that would prove to age particularly badly, the RT article on the Lindrum-Smith match suggests that it may well be that “the present popularity for snooker will turn out to be just a passing fancy, that the players will tire of constant potting, and welcome a return to cannons and long losers”. How wrong they would turn out to be. After all, snooker would go on to be the biggest game on green baize.

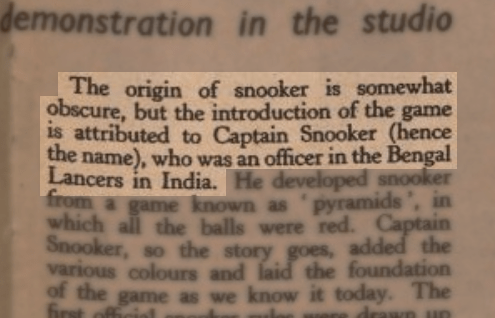

Plus, it certainly didn’t hurt that its origin story can be explained in one of the finest sentences ever published:

Though all that would come later. For now, it was deemed a sport not yet ready for the viewing public, small monochrome 405-line sets of the era perhaps not providing the optimal viewing experience. As such, following that initial pair of TV broadcasts for snooker on 14 and 16 April 1937, the sport wouldn’t return to BBC-tv (at least under a standalone billing) until 1950.

The dawn of the atomic age didn’t do too much to make snooker a fixture on British TV, however. The decade only saw a smattering of matches broadcast, including “Walter Donaldson (Present World Champion) v. Joe Davis (Retired Undefeated World Champion)” in September 1950. Throughout the decade, the not-as-retired-as-you-may-have-thought Davis featured more than any other player, such was the box office (well, TV licence fee) appeal of the sport’s most decorated player. Even where he wasn’t a competitor in the televised game, such as 1952’s John Barrie-Rex Williams match, he would turn up to perform a few trick shots between frames, such was his appeal.

Come January 1955, a special session of snooker was broadcast to mark the final event at snooker’s then spiritual home, London’s Leicester Square Hall, the centrepiece of the event being an exhibition match between Joe Davis and his brother Fred – himself no slouch on the baize, going on to win eight World Championships between 1948 and 1958.

As the decade progressed, most snooker coverage was folded into the weekly Sportsview round-up, which featured a “Sportsview Potting Competition” that allowed keen cuesmiths to challenge a top professional. And not just in any standard game of snooker, but a specific layout that proved a little more exciting (and more suitable for a segment of a programme just thirty minutes long). Another strand that proved popular was a feature where Joe Davis – playing solo – would attempt to score as high a break as possible within two minutes. The sporting spectacle was slightly undone in one edition where the referee, displaying his keenness to replace a coloured ball as swiftly as possible, accidentally scattered the remaining in-play balls as he did so.

The only standalone coverage of this era came from The News of the World Tournament, which pitted the best players against each other in a round-robin “American-style” format that was considered by many to be of greater importance than the ‘real’ World Championships – not least as the latter no longer featured people’s favourite Joe Davis.

By 1958, Saturday sporting action was safely enclosed in a great big Grandstand umbrella, with initial episodes making great play of challenge matches featuring, inevitably, Joe Davis. And Grandstand provided a safe haven for snooker for much of the next decade, the sport providing a perfect alternative to throw to whenever an outdoor event found itself hamstrung by unpredictable British weather. However, acting as the sporting equivalent of a supply teacher was no life for a proud sport, and once the Beeb’s favourite player finally retired from the sport in 1964 (Joe Davis, as you’ll have guessed), it seems the BBC had lost interest in the sport. Basing much of your coverage around a single superstar in the twilight of his career hadn’t been much of a long-term plan, as it turned out. When Grandstand producer (and snooker fan) Lawrie Davies left the corporation for a role at Yorkshire in 1965, snooker coverage would also depart the BBC.

On the other side, ITV had been having a lot of success with tournaments largely based around the amateur snooker scene. In 1961, this had involved putting together a tournament that saw four top amateur players face off against a quartet of players from the then-tiny pool of professional players. The matches were in a much friendlier TV format – just five frames per match, broadcast live and being much more competitive than the BBC’s exhibition-match coverage – but given the nature of the game, an keener desire to win often led to cautious matches concluding off-screen, as ITV’s attention had long drifted to the classified football results.

Still, what was there was more compelling than Grandstand’s coverage of the Joe Davis Globetrotters, especially in 1962 when amateur player Mark Wildman made the first ever televised century break on ITV, but with monochrome sets still in use, even that wasn’t enough to keep viewers queueing up (ignoring the easy snooker pun, there) for live coverage – especially when there’s no guarantee they’d get to see the final black of the final frame being slammed home. Conversely, matches being settled within just three of the five frames meant coverage finished much earlier than schedules anticipated, leaving a production team frantically trying to fill an additional hour and hardly resulted in tense, captivating snooker.

This lack of popularity caused concerns for the Billiards Association & Control Council. If only more matches lasted the full five frames, and also happened to be wrapped up in a way that meant everything was done and dusted before the vidiprinter clicked into life with the football scores.

Then… that started to happen. A lot more often. Wahey! Exciting snooker! This is what the public wants! Great job everybod… hang on, the Sunday Times have rumbled what’s been going on.

The real giveaway came on 28 January 1967. A invitation match on World of Sport between George Humphries and Ray Edmonds was billed as “a five frame thriller”. In the Sunday Times expose the following year, Edmonds came clean: “It was a five-frame thriller because we wangled it that way.”

It hadn’t been easy. At least according to Edmonds, Humphries had been so off his game, Edmonds accidentally won the second frame of the match, and had to put in some concerted cackhandedness to lose the third and fourth frames. By the time the fifth – and only deliberately competitive – frame came around, both players were so full of yips both players struggled to regain any sense of form. And the viewing audience likely reasoned they’d see a more skilled session of snooker down at the local hall at chucking out time.

This was far from a one-off. In the Sunday Times piece, former chair of the Billiards Association and Control Council Harold Phillips admitted that players of televised exhibition matches were given a reminder that “This is entertainment, you’re evenly matched and I do hope it’s all on the final frame”. Perhaps he followed that up by saying “wink wink”, the report doesn’t make it fully clear.

The issue hadn’t been restricted to matches on ITV. Former world champ Fred Davis stating that the BBC would “look on [close matches] favourably, if you understand what I mean”. As a result, Davis began to treat his exhibition matches on the Beeb as “five frames of comedy”, adding that he hated “taking part in something that’s not genuine”. And so, with the scandal scaring ITV away from the sport and the BBC long having given up on it, snooker would be absent from TV screens entirely.

That was, until the advent of colour television on BBC2 and the introduction of a brand new, and very different knockout tournament. One that wouldn’t need thrown frames to manufacture excitement.

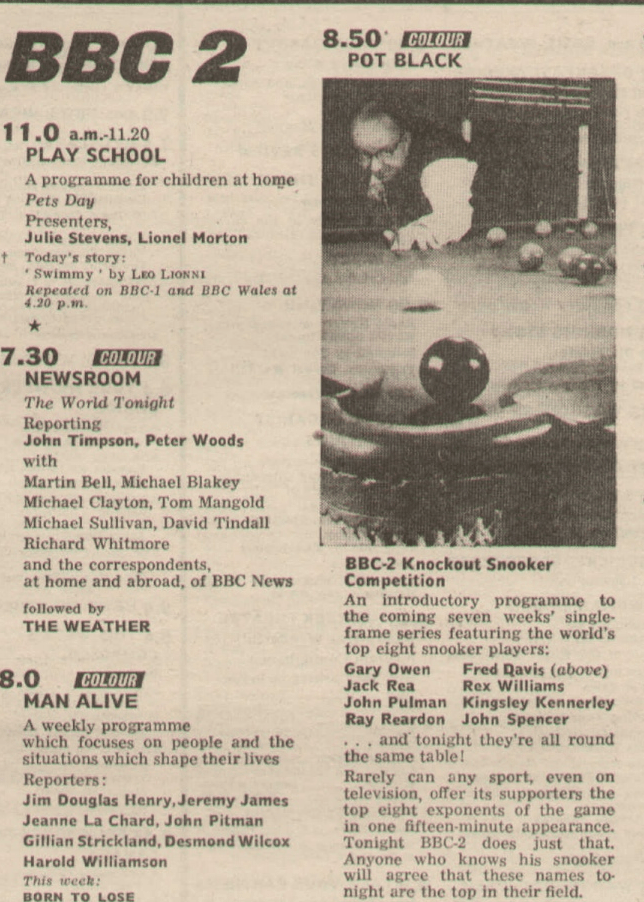

“Rarely can any sport, even on television, offer its supporters the top eight exponents of the game in one fifteen-minute appearance. Tonight BBC-2 does just that” boasted the Radio Times listing, and that’s exactly what was on offer here.

Each Wednesday evening, sandwiched between a weighty fifty-minute documentary and an episode of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, a single frame would be played between two of eight top players in a (largely) knockout competition, with one player winning the Pot Black trophy at the end of each series. For those new to the sport, the professionals would be on hand to offer advice (“instead of a pointer, these teachers use a billiard cue”), though given the modest fifteen-minute slot afforded early episodes, any lessons would need to be swiftly delivered.

Despite the popularity of Pot Black, coverage of regular snooker matchplay was still restricted to the BBC’s generic sporting strands. That was to change in the late 1970s, with BBC producer Nick Hunter keen to capitalise on the popularity of the quickfire series. If pre-recorded single frames could attract a BBC-2 audience of four million, Hunter felt that full coverage of snooker tournaments – freed from the shackles of brief Sportsnight highlights – could prove a hit. Players like Ray Reardon and Alex Higgins were helping to forge a new image for the sport within Pot Black, maybe viewers would like to see more of them?

The water was tested with highlights of the semi-final and final of the 1977 Embassy World Professional Championship being broadcast, and proved to be enough of a hit to expand coverage for the following year’s Championship. Late-night fifty-minute highlights packages were broadcast on each of the tournament’s two weeks, with live coverage included on each Saturday’s Grandstand, and live coverage of the final being broadcast on BBC-2. Despite the highlights airing in a slot nudging midnight, an audience of four million grew to seven million by the end of the tournament.

By 1980, viewing figures for latter stages of the World Snooker Championship topped 14m, increasing to 15.6m for the following year’s final. It didn’t hurt that the big tournaments were slimmed down to provide a more compelling spectacle. While final matches back in the 1940s would feature 145 frames spread across a fortnight (not necessarily all at the same venue), by 1981 it was down to a much friendlier Best of 35.

With the coverage proving to be a hit, the number of hours broadcast from each tournament increased. And so did the viewing figures. Major matches soon found themselves being broadcast live on BBC-1, or passed between BBC-1 and -2 whenever trifles such as the News needed to be broadcast on the main channel, ensuring keen viewers wouldn’t miss any action. There was a junior edition of Pot Black. Ray Reardon appeared on Parkinson. Recaps of each spring’s World Championships were compiled for broadcast over Christmas.

Snooker was conquering the country. At a time when going to a football match could end with you getting a dart in the eye, staying in to watch snooker seemed a much more attractive option. The prize money was growing, top players were becoming household names – at least 78% of Britain’s Dads would routinely put their glasses on upside down and say “look everyone, I’m Dennis Taylor!” throughout the mid-1980s. Even ITV tried to get back on board, but with several regional franchises snootily favouring their own programming in off-peak slots, the BBC was where the competition sponsors preferred their tournaments to be. Though ITV still cheekily snagged another TV snooker first, Steve Davis bagging the first-ever televised 147 during the light channel’s coverage of the Lada Classic.

Cigarette companies couldn’t advertise in ad breaks on ITV, yet their products were being beamed into twenty million sets of eyeballs on the BBC, which helped fund generous tournament sponsorship packages. During actual programmes! It seemed the gravy train would never stop.

The peak came, as every schoolchild knows, in the 1985 World Snooker Championship final, the match between Steve Davis and Dennis Taylor attracting the largest-ever BBC-2 audience, and the UK’s biggest-ever post-midnight audience, with 18.5 million viewers as Taylor’s final black finally went down.

Of course, nothing ever lasts forever (apart from Keith Richards and this list of TV programmes), and in 1990 something happened that would start to chip away at the all-conquering snooker mothership. And by ‘something’, I mean someone. And by ‘someone’, I mean Stephen Hendry.

In the 1980s, snooker unquestionably had personality. Whether it was Dennis Taylor’s glasses, Bill Werbeniuk’s ability to claim lager as a business expense or Jimmy Whirlwind White, it just had something about it. Chas and Dave don’t just make records with anyone, you know. Even the player pilloried for being boring, Steve Davis, turned out to be a great guy, writing a comedy book, acting alongside David Cross in a US cable TV sitcom and then becoming an underground electronica artist (all true!). But Stephen Hendry came along and hoovered up most of the big snookering gongs for the next decade. Here was someone truly laser-focused on upping his game, who’d grown up in a world quite different to the fags and sleaze era of the sport. And, at the time of his first title, he was just 21 years old. He was going to be around for a long time to come.

By 1992, snooker had the brand new (football) Premier League to contend with. And so, as one successful-but-dour Scot wowed supporters (and infuriated rival fans) as a refreshed sport wowed a growing TV audience, another started turning people away from his own. The blame didn’t land purely at Hendry’s sensible shoes, of course. Coverage had perhaps reached saturation point, and while the number of hours devoted to snooker on the BBC remained at a similar level for years to come, audiences started to decline. A series of more, well, professional professionals started to take hold, meaning any excitement for the casual viewer was restricted to seeing if Jimmy White could finally win the World Snooker Championship title. SPOILER: He couldn’t.

And yet, as snooker started to wane in popularity in the UK, it began to grow in popularity elsewhere. Thailand’s James Wattana became the first Asian player to reach the semi-finals of the World Snooker Championship in 1993. By 2000, Hong Kong’s Marco Fu was ranked in the world’s top twenty players, soon to be followed by Chinese star Ding Junhui. Other Chinese players such as Liang Wenbo and Liu Song would soon join the list of ranked professionals as the sport grew in popularity throughout Asia, but the biggest name on the millennial snooker scene was very much homegrown.

Ronnie O’Sullivan did more than anyone to bring to sport back to public attention, having bagged his first century break at the age of ten, and his first competitve 147 at the age of just 15. In 1997 he’d bagged the fastest competitive 147 in history, taking just over five minutes to notch a maximum break at the World Championships. Ferocious at the table and refreshingly outspoken away from it, O’Sullivan would go on to be as successful as any player in the modern era. But – crucially – his habit of collecting World Championship gongs was a little more spread out than Hendry’s reign of no-error, allowing others to win them once in a while. So, that’s nice.

And best of all, he provided the sport with a redemption arc – slipping right down the world rankings from the early 2010s, slipping to 28th in the middle of the decade (albeit still picking up world titles in 2012 and 2013), before clambering back to the top in 2019, and regaining his world crown in both 2020 and 2022.

Snooker still isn’t as popular as it once was. While other bar-room sports such as darts have enjoyed a massive rise in popularity since the turn of the century – the game of arrows having its own popular Premier League competition – snooker has never really attempted such a reinvention. And yet, it’s quietly retained a loyal audience, and it’s far less parochial than it once was. While the glitz and glamour of the sport once rose no higher than matches being played at Blackpool Tower, ranking tournaments now routintely take place in Latvia, China, Belgium or Germany, while still retaining a spiritual home at Sheffield’s Crucible. The British TV audiences may have slipped, but the global TV audiences are higher than ever.

And best of all, current players are no longer expected to share a television studio with Jim Davidson. The sport has certainly come a long way.

Blimey, that was an epic journey. Well done if you stayed awake through all that. Tune in again soon for the next update, and until then let’s all hold our collective breath that number eight on the list isn’t Big Break.

4 responses to ““Perhaps I Ought To Chalk It?”: The 9th Most-Broadcast BBC Programme Of All Time”

I had a black and white portable telly as a student and I used to colour in the balls with felt tipped pens.

LikeLike

EXCELLENT.

LikeLike

“And so, on 14 April 1927, snooker was introduced to the television audience for the first time.”

Wow! Before television had even been introduced to the UK?

Typos apart, a really interesting article. Thanks.

I was originally sceptical whether snooker would make the list at all. I’m glad to say that I included it at #7 on my list of predictions, but only after a bit of persuasion!

LikeLike

Doh! I’ve now corrected that (thanks for the heads up), and also added supporting links for my weighty claims about Steve Davis being way more interesting than 99% of sportsmen (which I’d meant to do in the first place, but forgot).

LikeLike