“We interrupt this programme to bring you a football game.”

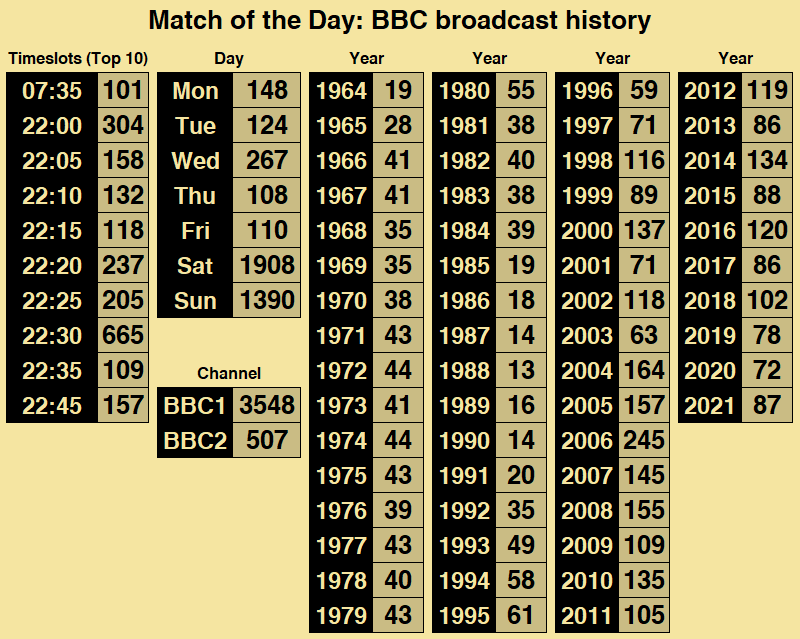

16: Match of the Day

(Shown 4055 times, 1964-2021)

Well, here’s one that was always going to appear, and one where I probably need to clarify the criteria for inclusion. In general with this list, where something had specific programme branding applied to it and it keeps to the core format of the programme, I’m counting it. So, Nationwide Election Special counts, Tweenies Songtime doesn’t. Postman Pat Special Delivery Service please step forward, This Morning With Anne and Nick’s Live Autopsy Hour not so fast.

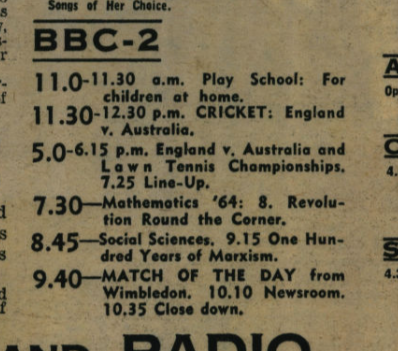

That gets a little more complicated with Match of the Day. For one thing, the first eleven times the title ‘Match of the Day’ appeared in TV listings, it had absolutely nothing to do with football. While MOTD as we’d come to know it first aired on Saturday 22 August 1964, Match of the Day first appeared as a programme title a whole two months earlier. A total of eleven editions of ‘Match of the Day’ aired in relation to the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Championships in 1964 before the moniker was first applied to kickball.

The MOTD branding would go on to become closely aligned to both football and (during Wimbledon fortnight) tennis highlights, with the latter sometimes made clear in the programme title (as Match of the Day from Wimbledon or Wimbledon [YEAR] Match of the Day), but sometimes not.

The other complication comes in defining what makes up the ‘core’ MOTD experience. Saturday night football highlights are the main thing you’d associate the brand with, but it’s also been used for live football coverage (sometimes as Match of the Day Live, International Match of the Day or Match of the Day: The Road to Wembley, sometimes as just plain old Match of the Day). And what about Match of the Day 2? Does that count? How about Match of the Day Greats, or …Kickabout, or …Top 10? How about lockdown gap-filler Match of Their Day?

Right, to try and get some kind of vaguely accurate figure here, I’m going to go with the following rule: If it’s tagged as Match of the Day, and the bulk of the content is footage from a football match (or matches, either live or highlights) of a contemporary match, it counts. If it’s not one of those things (so, Kickabout et al), or doesn’t have the MOTD branding, it doesn’t count. Settled? Good.

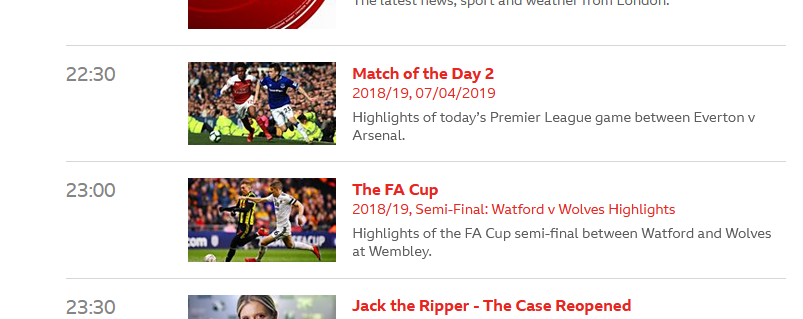

The waters are, of course, further muddied by the MOTD branding not always being used in programme listings. Since 2014, much of the BBC’s live or highlight coverage of The FA Cup has been billed as ‘The FA Cup’, keeping it away from the (now) more Premier League-focused MOTD name. Which means that, in this age of iPlayer and rights issues, the two sets of highlights are now kept in separate containers. Even when they’re next to each other in the schedule.

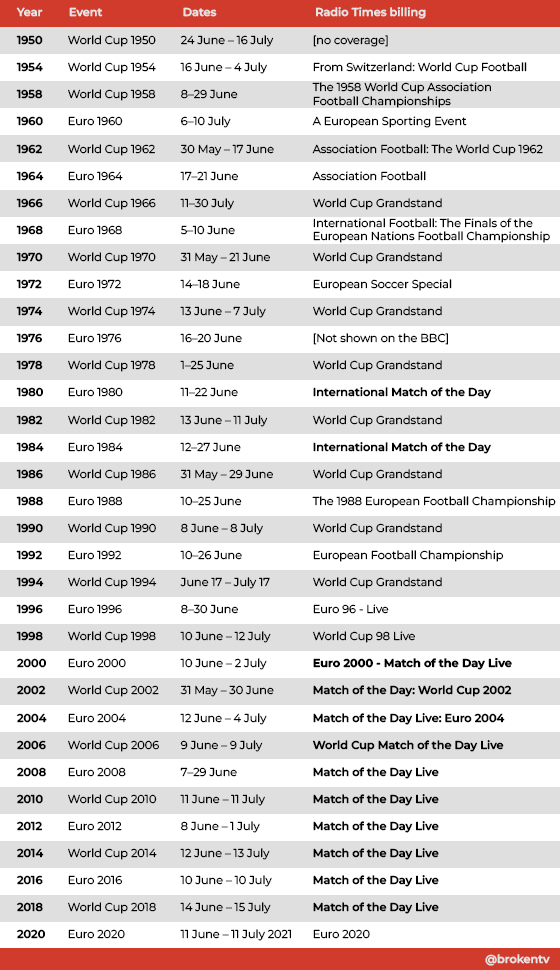

The title World Cup Match of the Day was used when nightly highlights round-ups were broadcast in 1974 (live matches then going out as World Cup Grandstand). Then that title lay dormant for 15 years, with the programme title reused for highlights of Italia ’90 qualifiers in 1989, provided they were on a Saturday – midweek qualifier highlights went out as part of Sportsnight. That is until October 1989, when World Cup Match of the Day was used for a live (midweek) broadcast of the Poland v England qualifier. Then, the programme title hibernated until the 2006 World Cup in Germany, except for the highlights packages for Euro 2000 that used “MotD at Euro 2000” but not for the live matches… look, here’s a table of RT billing titles for every major international football tournament since 1950. Titles included in MotD’s episode count are in bold.

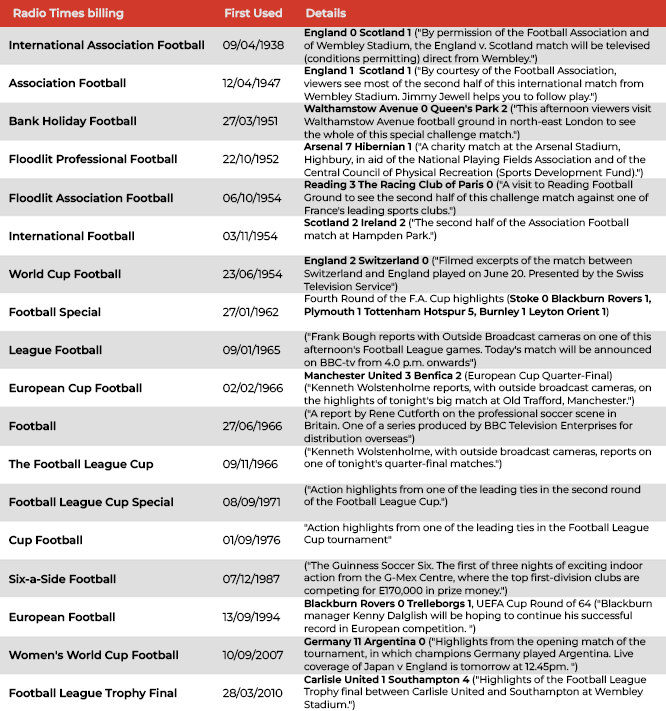

Anyway, let’s rewind a bit. Football on the BBC has gone out under a variety of guises – hey, here’s another largely pointless table, this time of non-MotD football match billings in the Radio Times:

So, it’s probably for the best that they settled on another programme title. The above isn’t even a comprehensive list – between 1971 and 1997, the Sportsnight Special branding was used for midweek football matches, mostly but not exclusively for those broadcast live (first: FA Cup Third Round Replay highlights, last: live coverage of AS Monaco v Newcastle United in the UEFA Cup).

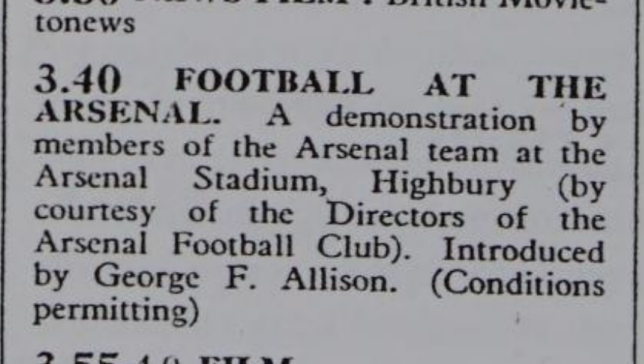

The BBC’s first televised association with Association (Football) dates all the way back to September 1937. That inaugural coverage was, as you may well already be aware, a thrilling tussle between Arsenal and… Arsenal Reserves at Highbury. Yep, fifteen minutes of a training match. While this could easily have been some filmed footage flung out as part of Newsreel, the BBC didn’t take that easier option. The Beeb’s brand new mobile television unit travelled to Highbury to broadcast the footage live. The first ever billed football match (as shown below) was indeed “a demonstration by the members of the Arsenal team” on 16 September 1937, but live footage of football first went out a day earlier – two minutes of soundless but live footage of the Arsenal team went out at 3.45pm the previous day, as part of magazine series Picture Page.

Such was the cost of sending the mobile television unit (around £35, or the price of a pie at Wembley in 2023), a series of broadcasts from the ground were requested to make the whole affair a little more cost effective. As a result, a total of three transmissions were made from the ground, plus (following that brief initial broadcast on Picture Page) a test transmission of Arsenal Reserves versus Millwall Reserves was beamed back to a special viewing room at Ally Pally, so BBC bosses could gauge how suitable this football lark was for public consumption.

The second billed visit to The Arsenal occurred on 17 September that year, which led to another broadcasting first: George Male becoming the first footballer ever to be interviewed on live television. On being questioned about the diversity within the Highbury playing staff, Male proudly proclaimed “they are from Scotland, Yorkshire, Wales, all over the place… provided they are British subjects. We couldn’t put a foreigner in the team”. Plus ca change, eh? As a result (of the broadcast, not Male’s xenophobia), the BBC would go on to broadcast the FA Cup Final between Preston North End and Huddersfield in 1938, followed a year later with the Portsmouth versus Wolves final – the latter listed alongside the caveat “unless anything untoward happens” in the Radio Times (and a warning that “no rediffusion in places of public entertainment will be permitted”).

Following the war, the BBC were keen to show more live football for the demobbed masses, but there was a problem. The Football League – gatekeepers for the bulk of English professional matches – were dead against the idea, calculating that allowing the still-small television audience to watch coverage on tiny monochrome sets would be preferred to the full-3D, full-colour, full-Bovril matchday experience, and stop attending matches in person. Luckily for the BBC, the FA in general were more receptive to the broadcaster. Less luckily for the BBC, technology at the time limited them to covering events within a 20-mile radius of Alexander Palace.

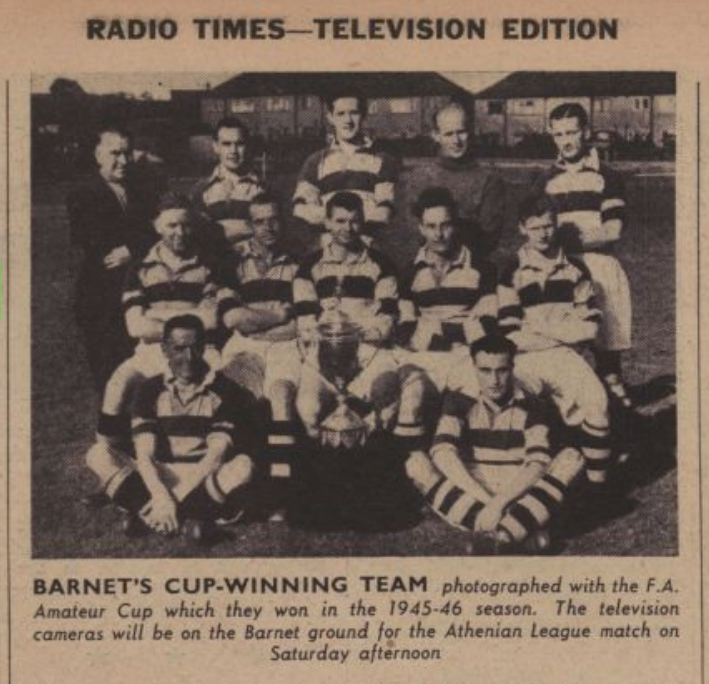

As a result, the next televised football match, taking place on Saturday 19 October 1946, was from the lofty heights of the Athenian Football League, with Amateur Cup holders Barnet entertaining Wealdstone. Even then, the broadcast was far from simple – the permission of a local resident had to be sought so BBC engineers could borrow their phone line, and from another resident to plonk some scaffolding for cameras on their allotment. Thus the programme budget was duly increased to include compensation for damaged crops.

That wasn’t the end of the technical hitches. Despite the promise of “part of the first half and the whole of the second half” in the Radio Times, bad light ultimately curtailed the live broadcast fifteen minutes from the end of the match.

Despite those obstacles, the broadcast was deemed a success, and the BBC would go on to broadcast further (non-Football League) matches from the London area.

By 1954, the popularity of television had grown, along with the demand for televised sport. As a result, Head of Sport Peter Dimmock along with Paul Fox devised Sportsview, the BBC’s first midweek sporting magazine programme. This offered football match highlights alongside other sports, and soon became must-see viewing for sport fans lucky enough to own a television receiver. That popularity led to Sports Special, a Saturday night spin-off for the series packing a more football-focused remit, with Peter Dimmock taking to the Radio Times to provide exciting details on how “a helicopter, two aeroplanes, plus a fleet of motor-cycles and fast cars” would be employed to rush filmed reports from stadia to studio each week.

Sports Special would go on to run for ten years from 1955, accompanied in October 1958 by Saturday afternoon stablemate Grandstand. However, the very march of progress that made the programme possible in the first place (including, of course, the thrilling assistance of fast cars and helicopters and possibly at least one Milk Tray Man) would lead to its downfall. Match reports being shot on 16mm film meant that on arrival at the studio, footage first had to be processed, returned as wet negatives and frantically edited at Lime Grove by harried editors praying that they’d get the job done in time for transmission. The reliance on filmed reports (and the budget only allowing for a single camera at each match) also carried the risk of a crucial goal being slammed home while the camera operator was changing reels.

Videotape and multi-camera coverage were still only on the horizon, but Sports Special’s days were numbered. What was once a regular weekly treat became a more sporadic offering, and despite rebranding for most weeks as Football Special from late 1961, in April 1965 the programme would air as a Saturday night strand for the last time, by now on the rechristened BBC-1, with a broadcast of that day’s England v Scotland match from Wembley.

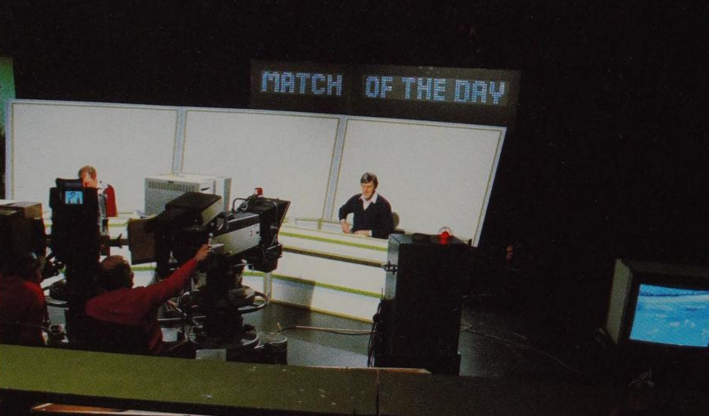

But! Hope for football fans was not lost. Over on upstart BBC-2, a new programme had arrived in 1964, opening with the classic Wolstenholme words “Welcome to Match of the Day, the first of a weekly series coming to you every Saturday on BBC-2. As you can hear, we’re in Beatleville for this Liverpool versus Arsenal match”, and ending with a score of 3-2 to the Mighty Reds.

It would go on to become quite popular.

The write-up for that first-ever episode in the Radio Times went as follows:

Today for the first time soccer fans can watch a feature-length version – as opposed to a potted ‘highlights’ version — of a regular League fixture. Which one? That, by agreement with the Football League, remains a secret until 4.0 this afternoon. But Bryan Cowgill, BBC-tv’s sports chief, promises that it will be a top match.

The agreement by which BBC-tv won permission for this came after careful negotiations between Bryan Cowgill and League Secretary Alan Hardaker. It allows for fifty-five minutes of coverage, enough to show the whole development of the game, and for its screening at a more popular hour.

Up to now we have only been able to show ten-minute edited films of any given match. which, effectively meant a machine-gun succession of goal-goal-goal,’ says Cowgill. ‘Now we can fall in line With BBC-2’s policy by offering “depth” treatment of our most popular sport’. To those who think this breakthrough is a further blow to turnstile takings, he offers his experienced opinion that ‘television never kept anyone away from the best in sport.’

In charge of the new venture as producer is Alan Chivers, BBC-tv’s most experienced soccer specialist. He intends to make full use of the technical advantages of 625 lines, and says: ‘We’re no longer restricted mainly to the close-up, With 625’s greater definition we can use wider shots without losing clarity, and so show much more of the overall pattern of a game.’

Radio Times Issue 2128, 20-26 August 1964

Following the 1966 World Cup, famously won by A British Team Wearing Red (haven’t checked, I presume it was Wales), MOTD made the move from BBC-2 to BBC-1 for the 1966/67 season. Although the programme would move back to BBC-2 for a week in November 1968 so that the first colour edition of the series could be shown. Any football fanatics without a 625-line set that week at least got to watch Hitchcock’s Anatomy of a Murder on BBC1 that night. It wouldn’t be until 15 November 1969 that colour MOTD first arrived on BBC-1 – on the channel’s first official day of colour TV.

Transition to colour TV aside, the core remit of the series – football highlights on a Saturday night – remained unchanged for a long time. Even when events called for a special episode of MOTD, it was usually affixed to standard match highlights, as had been the case on 10 Jan 1970 and the excitingly-billed “Match of the Day Special: 1970 World Cup Draw“. This contained the exciting curveball of having David Coleman reporting from Mexico City’s Maria Isabella Hotel, where the 16 qualifying nations discovered who they’d be playing that summer (“Presented by Telesistema Mexicano”, no less). Even then, as befitting the programme, the bulk of the content that week was still of match highlights from a suitably sodden football ground.

A year before that Mexican jamboree, MOTD had added the first ever slow-motion replays to their coverage, an innovation that would make a huge difference to the way football was covered. And those innovations were increasingly important. At a time when the USA and USSR were in a PR war to get the first boots on the moon, BBC and ITV’s respective football flagships were locked in a similar, if slightly less cosmic, battle.

The nature of ITV meant there was no network-wide football highlights programme – the whole story of football on ITV could fill an entry on its own – but the big hitter was undoubtedly LWT’s The Big Match, which tried to add a little Light Entertainment pizazz to the whole affair (oh, okay. Brian Moore and a desk with a phone on it). The battle ultimately became so intense that Michael Grade led a coup to snaffle up exclusive rights to the Football League in 1978, the move was famously reported in the papes as ‘Snatch of the Day‘. Which would have been quite witty had the pun not already been public knowledge since a 1974 anti-pickpocket public information film. Luckily, the Office of Fair Trading put a stop to that nonsense, and Match of the Day was safe. For a while.

The battle of the broadcasters intensified throughout the next few years, though there was a truce of sorts after the channels agreed to alternate ownership of the prime Saturday night highlights slot, meaning MOTD aired on Sunday afternoons throughout the 1980/81 and 1982/83 seasons. However, for 1983/84 there was a new, long-awaited change for both channels: live coverage of Football League matches. It’s almost strange to imagine such a thing at a time when almost every single match in the top five tiers of English football can (legally) be watched live, but that represented the first time live league football would be shown on TV since 1960. Highlights briefly faded into the background. Especially during the start of the 1985/86 season, when disputes over money meant TV was a football-free zone for several months. At least that led to Saint & Greavsie parading West Ham’s leading goalscorer Frank McAvennie around London to see if anyone would recognise him, which is quite fun.

1988 saw a dramatic change to coverage for the Beeb, with ITV paying a (then-)whopping fee for exclusivity. It certainly seems quaint now, but paying £44m for 21 live matches per season was big news at the time, not least as it restricted MOTD to coverage of the FA Cup (and for the most part, a rebranding to Match of the Day: The Road to Wembley).

As football’s post-1990 popularity soared Skywards (insert a Waddle penalty gag here if you must) even bigger changes were afoot. But then you probably already know all about that. At least that meant top division highlights returned to the BBC.

And – if we all pretend those few years of Andy Townsend’s Tactics Truck et al were just a national hallucination – that’s where they’ve stayed ever since. And indeed, the lockdown-era Project Restart even led to the return of Live Top Tier Football to BBC1 after a gap of 32 years.

The mission statement of the programme has certainly changed a lot since Kenneth Wolstenholme’s original trip to Beatleville. The very thing original producer Bryan Cowgill was so happy to be leaving behind – “ten-minute edited films of any given match” – is now the core product of the programme. But, in a world where watching live football on TV is largely restricted to those with a disposable incomes or an illicit IPTV hookup, it’s still appointment television for many, and for everyone else it’s just nice to know it’s still there.

After all, we’ve now seen a vision of the future without Match of the Day. It wasn’t pretty.

NOTE: If you’d like to read a lot more about the history of football on British TV, be sure to take in Steve Williams’ superb Goalmouths over on OffTheTelly.

15: Doctors

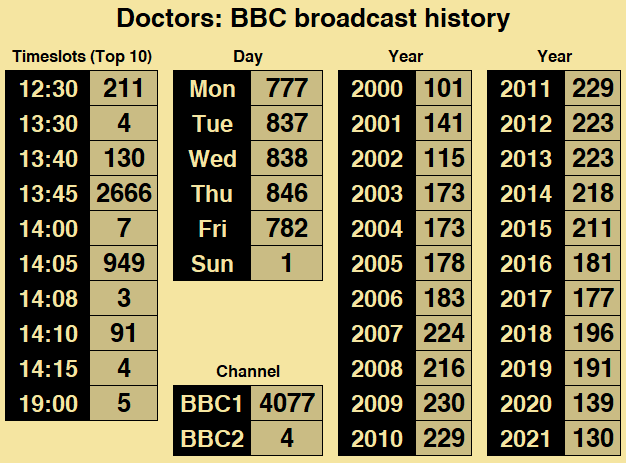

(Shown 4081 times, 2000-2021)

For a genre of television that has seemed utterly omnipresent since the days of Stooky Bill, it’s actually a little surprising to learn that medical drama series were few and far between in the early days of British television. In the early days of the BBC Television Service, the closest you were likely to get was seeing a concert by someone who’d left the medical profession for the world of music, such as pianist Leslie ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson (5 Dec 1936, Starlight) or Norman Hackforth (4 Feb 1937, The Composer at the Piano).

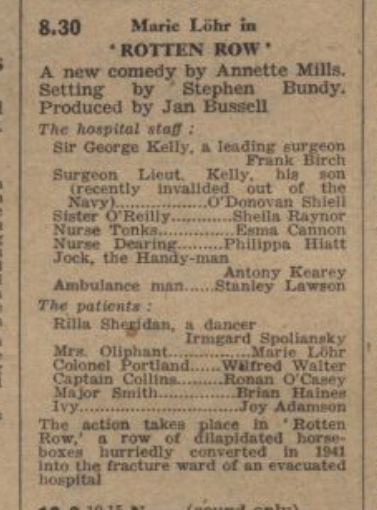

As was the style at the time, there would occasionally be serious factual programming based on medical matters, especially in the post-war years, such as 1947’s I Want to be a Doctor, but dramatic fiction from within doctorly settings were a feature that television simply didn’t seem to fancy. It’s tempting to suggest that the medical profession was deemed sacrosanct when it to TV’s myopic gaze, but that’s swiftly disproved by there being a smattering of comedy plays about the profession. May 1947 saw Annette Mills’ comedy feature Rotten Row, where a dilapidated row of horse boxes is converted into a fracture unit next to an evacuated hospital in post-war London (I repeat: a comedy), while August that year saw the screening of The Amazing Dr Clitterhouse, a comedy thriller by Barre Lyndon.

By the late 1940s Britain finally had a National Health Service, so it’s perhaps understandable that television preferred to spend airtime demystifying what went on behind hospital doors. As a result, factual programmes often made an appearance in the Radio Times, such as 1948’s Mass Radiography, (“The Medical Officer in charge of a Mobile X-Ray Unit belonging to the North-West London Regional Hospital Board demonstrates a new technique of diagnosing chest diseases in their-early stages”), or 1949’s medical documentary series Matters of Life and Death (“Episode 7: Dr. F. Avery Jones and Mr. Norman Tanner, a physician and surgeon who have made a special study of gastric and duodenal ulcers, discuss their prevalence and show how they are diagnosed and treated”). All very worthwhile, but hardly using matters medical to offer a sense of escapism for the TV audience.

That changed in 1951, with a six-part television adaptation of Anthony Trollope’s 1855 book The Warden. The first of the Chronicles of Barsetshire series, the book followed the fortunes of Mr Septimus Harding, an elderly warden from Barsetshire-based Hiram’s Hospital. That offering aside, it took the launch of ITV in 1955 to successfully transplant the notion of a medical TV drama into Britain’s cathode-ray tubes. Emergency Ward 10 (ATV, 1957-67) became one of the nascent network’s breakout hits, albeit one that came about due to a misunderstanding. It had been suggested to programme creator Tessa Diamond that a show about daily hospital life might be a hit. It was only after Ward 10 was created that her agent revealed the original suggestion was actually for a documentary series.

Once that happy accident was out of the way, the programme quickly became a success. So much so, in ten years on the air it clocked up a total of 1,016 episodes – including in 1964 one that featured an early example of an inter-racial kiss between two actors.

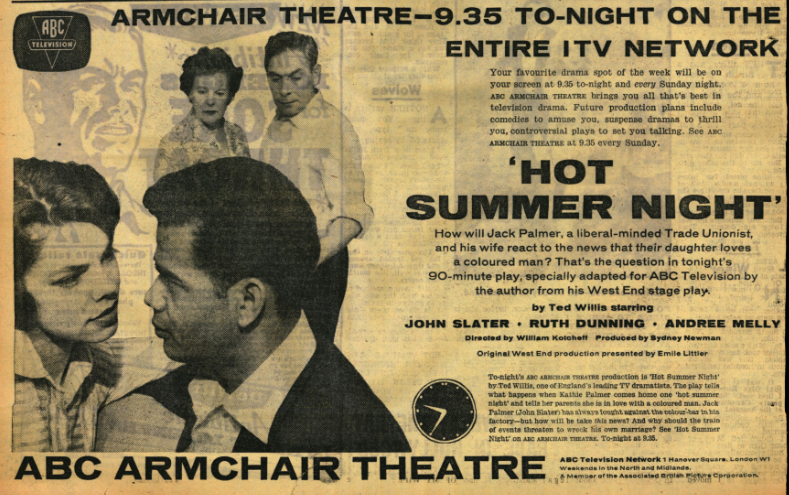

Aside: For a spell, it seems to have been considered television’s first-ever such embrace (coming a full four years before the Star Trek episode “Plato’s Stepchildren”). However, it was actually preceded by both Granada’s 1962 Play of the Week In Your Small Corner, and 1959 ABC Armchair Theatre play Hot Summer Night – both plays featuring Jamaican actor Lloyd Reckord.

Anyway, with Ward 10 proving a success, other medical soap operas would later appear in an attempt to rebottle that magic, such as General Hospital (ATV, 1972-79), Angels (BBC, 1975-83) and Children’s Ward (Children’s ITV, 1989-2000). On top of that, daytime TV found plenty of room for antipodean imports The Young Doctors (Nine Network 1976–1983, airing on ITV from 1982 and Sky Channel from 1989), A Country Practice (Seven, 1981–1994, shown on ITV from 1982 and Sky Channel – in primetime! – from 1984) and Shortland Street (TVNZ 2, 1992–, shown on ITV from 1993).

As the millennium (and to a lesser extent, the Willennium) neared, the previously-listed Holby City (BBC, 1999-2022) started a residency on BBC1. And, with that proving popular enough for BBC bosses to attempt a daytime version, this was followed a year later by the first episode of… Doctors. Yes, we’ve got to it at last. Phew.

Set in the fictional Midlands town of Letherbridge, the Chris Murray-devised programme follows events within the local doctor’s surgery and the nearby university campus surgery, along with those of the stakeholders within.

Commissioning a brand-new scripted drama to go out in the pre-news slot 12.30pm each weekday – a place you’d usually expect to contain an episode of Changing Rooms, Celebrity Ready Steady Cook or Bargain Hunt – was certainly a brave move by BBC head of daytime programming Jane Lush. To remain receptive to occasional viewers, the programme was to use self-contained stories featuring the key cast rather than having long-running plot strands (a la imperial phase The Bill). In addition, casting cosy drama series stalwart Christopher Timothy as key character Mac McGuire certainly wasn’t going to hurt.

To introduce viewers to the series, the opening episode aired in a primetime-adjacent slot of 6:35pm on Sunday 26 March 2000, with the first regular daytime episode airing the following lunchtime. Under the auspices of showrunner Mal Young, whose vintage included Holby City, Casualty and would later cross the Atlantic to exec produce The Young and the Restless, Doctors proved successful enough to be tried out in a 7pm weekday slot in the summer of 2000. However, it quickly became obvious that a rival soap wasn’t much of a threat to the Emmerdale behemoth, and it returned to the cosier confines of 12.30pm.

And that happy little niche was where it would stay for just over a year and a half, before shifting to a 2.10pm slot in November 2001 in a soapy double-bill with Neighbours. And that was where it stays for several years, Letherbridge being happily twinned with Erinsborough five days per week, making it a Doctors appointment you weren’t likely to miss (oh shut up).

However, in 2007 calamity struck. With the FremantleMedia demanding a whopping £300m from the BBC in return for the rights to Neighbours for the next eight years, the flagship show was instead set to move to Channel Five. The result: a major soap-shaped hole in BBC1’s daytime schedule. What was the BBC to do? Splurge a chunk of programme budget on nabbing the rights to Shortland Street? Fling on repeats of The Sullivans? Nope, by that point Doctors was doing well enough for it to be promoted into that key post-news slot, with the remaining episodes of Neighbours switching to its post-2pm slot.

Doctors continued to perform admirably for the lunchtime audience, but finding a companion for it proved a little more tricky. US drama show Monk was tried out in that slot during December 2007, before long the Neighbours burn-off episodes were restored to the slot while packing its bags and preparing for life on Five. Diagnosis Murder was given a run in that slot a few months later, but April 2008 saw the launch of the BBC’s new secret weapon: Out of the Blue. It was cool. It was sexy. It could air five days per week. And most importantly, it was Australian.

Set in the fashionable Sydney beach suburb of Manly, the action started with a group of thirty-year-old friends returning home for a high school reunion, only for the reunion to end in murder and an investigation into which of them done it. It couldn’t fail. And crucially, it had actually been commissioned by the BBC, so could be tailored to meet the needs and wants of a British audience.

Obviously, it failed. Big time. Ratings were so unspectacular, it was nudged over to BBC2 after just fourteen episodes on BBC1, and lasted less than a year before being cancelled entirely. Not to worry though, Five picked up the repeat rights to the series, and put them out on digital offshoot Fiver. I’m assuming for a much lesser outlay than they’d paid for Neighbours. Diagnosis Murder picked up the post-Doctors reins, and proved a much more popular companion. After all, it is the 62nd most-broadcast programme on the BBC of all time.

Speaking of Doctors (which is what we’re supposed to be doing here, of course), it was the bedrock of the BBC daytime schedule. By 2010, it was picking up a comfortable two million viewers per episode, regularly winning the daytime ratings war. Indeed, some episodes even rated as high as 3.5 million viewers, numbers that EastEnders producers would probably throttle Wellard for nowadays.

And as time went on, those viewing figures only continued to grow. By 2017, they were sitting at a comfortable 2.5 million per episode, at one point reaching a peak of four million (according to a Telegraph link I’m not going to pay to read, so we’ll take Google’s word for it).

Now, as will be abundantly clear from this update, I’ve barely ever watched an episode of Doctors. However, what has become clear to me is that the creative team behind it aren’t afraid not to try something thrillingly different from time to time. The most obvious example of this would be superbly titled episode “The Joe Pasquale Problem“, which involved a patient seeing everyone as Joe Pasquale (special guest for that episode: Joe Pasq… oh, you’ve guessed).

Better still, an episode airing on the telltale date of 31 October 2014 saw character Al “forced to confront his scepticism of the supernatural when he finds a whistle with mysterious powers”. Or, if you prefer, an episode of a daytime soap opera was used as an excuse to put on a production of M R James’ 1904 ghost story Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad. You don’t get that with Emmerdale, do you?

That’s the only episode of Doctors I’ve ever watched, and not going to lie – it was great. The modest budget of a soap episode really helped it capture at least a soupçon of the 1970s aesthetic of the original A Ghost Story for Christmas, which is handy as Jonathan Miller’s 1968 version of the same was a decidedly different beast from the annual anthologies it begat. That Doctors episode is on DailyMotion if you fancy seeing it. And so are plenty more, if you like the sound of the series and would like to catch up.

(By the time you finish that, I might have the next entry on the list written.)

That’s another one in the bag, which isn’t a literal bag. More ‘soon’, if I get out the habit of spending an hour researching something for the sake of a single sentence about something not really connected to the programme I’m meant to be talking about.

3 responses to “Paging Dr Clitterhouse! It’s The 100 Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes Of All Time (16 and 15)”

That was worth it just for the link to “Snatch of the Day” – my favourite PIF ever!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant, as always. Thank you for doing all the research so we don’t have to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Match of the Day(Shown 4055 times, […]

LikeLike