Bronze medal time! But first, here’s something that you may well float your retro TV boat if you’re enjoying this rundown.

Unstoppable word machine Ben Baker’s latest book – The Dreams We Had As Children – is out now, and it’s a bit of a cracker for anyone who grew up (or old) with a fondness for Children’s ITV. With the light channel’s nostalgia engine yanked out of a clapped out Cortina compared to the Beeb’s well-oiled retro roadsters, it’s not a broadcaster that makes much of its archive, so it’s left up to others to pick up the slack. And that’s just what Ben has done here, looking at forty key programmes from CITV’s forty years on air, from Danger Mouse to Dave Spud, and pretty much every point of interest in between. Plus, lots of other fun gubbins relating to those key CITV years.

If, like me, you’re cursed with a mental grasp of the past that requires constant research to confirm that, no, Gilbert’s Fridge actually was a thing that somehow got made and broadcast (something the Children’s BBC would never have dared do), this book doubles at an essential comfort blanket for the brain. And that’s as well as being a thoroughly entertaining read in its own right. Hurrah! If that sounds like something you’d like, go treat yourself. Go on, it’s Christmas.

Okay, on with the list, and a visit to those…

3: EastEnders

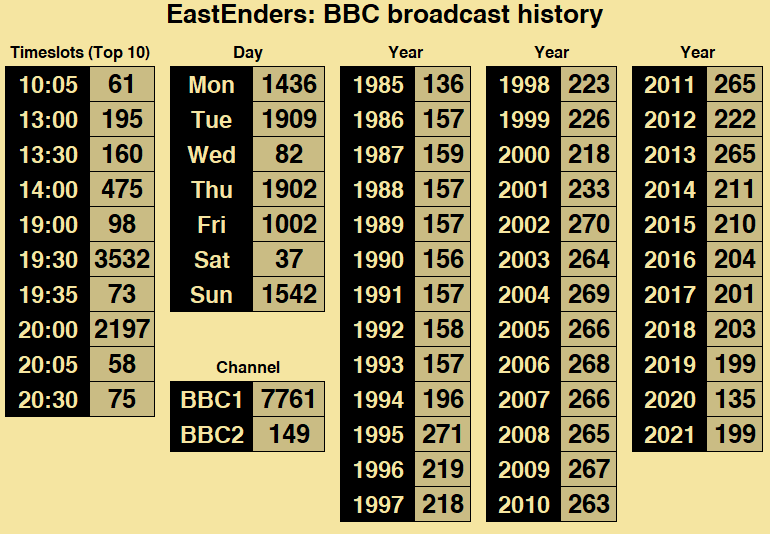

(Shown 7902 times, 1985-2021)

Once upon a time, there was a new soap op… sorry, ‘continuing drama series’. Well, ITV’s Coronation Street was huge and Crossroads also had an loyal audience, so it was decided that formula could easily be copied elsewhere. Corrie was about life in the north of England, Crossroads covered the Midlands, so how about setting it in the south of England? Where some of the main characters run market stalls, that should get them all interacting with each other, rather than just sat inside all day. And, as luck would have it, there’s enough spare space at Elstree to build a great big outdoor set for it.

And so, it launched to no small amount of fanfare. And, despite many in the national press getting a bit sniffy about it, it was a hit with the public. Indeed, before long it was top of the TV ratings, and one of the biggest hits of the decade. Before much longer, the scripts were getting tightened up, the more popular characters were being given more airtime, and finally the critics started to applaud the series. It seems like it could do no wrong.

Within two years it was gone from our screens, never to be seen again.

That programme was, of course, ATV’s Market in Honey Lane.

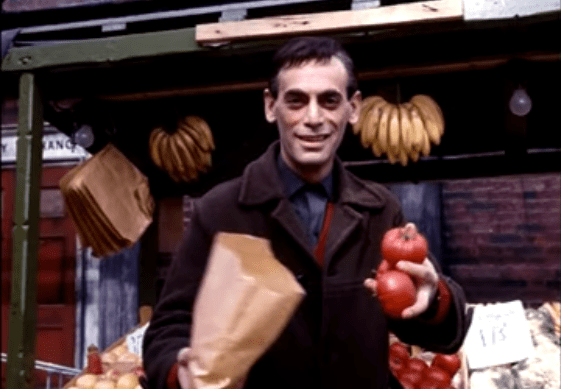

Market in Honey Lane came about after script editor Louis Marks was intrigued by his wife Sonia’s tales of goings on while shopping at London’s Berwick Street market, and set about putting together an idea for a drama series. The idea was pitched to ITV franchise ATV, who picked up the series in 1963 with an aim to use it for the surely-soon-to-launch ITV-2. After the second commercial channel failed to materialise, the idea sat on the shelf for a spell. A few years later production was finally set into motion.

The premise was even grittier than its grimy Manchester stablemate, with the £15,000 set including a betting shop, a strip club and an erotic book shop. That approach backfired somewhat before the first episode had even aired, when thieves broke into the set and stole stock from the “book shop” including titles such as “Fanny Hill”, “Variations in Sexual Behaviour” and “How to Make Love in Five Languages”. There’s a sentence that’ll help the site’s SEO, I’m sure.

ATV’s marketing department sent out the lofty claim that “you can learn more about life by standing in Honey Lane and breathing deeply for five minutes than by travelling around the world”, and waited for everyone to tune in.

Following the debut episode on Monday 3 April 1967, critics weren’t impressed. Writing in the Daily Mirror, TV critic Kenneth Eastaugh decried the opening episode as “even more banal than Crossroads”, dismissing the production as “turned out by folk who have never seen a production more ambitious than a church bazaar”. Readers weren’t much kinder – the Sunday Mirror’s “Be a TV Critic” letters page seeing it described as “The worst programme I’ve ever watched” (Mrs B A Spurr, Langford) and “A real flop, this one” (W Bucknall, Gravesend).

It wasn’t long before the programme improved – just six weeks after the poorly-reviewed debut, the Daily Mirror’s Michael Hellicar declared that Honey Lane was the highlight of each Monday night’s schedules, noting that “no longer are there a dozen or more characters all trying to be the star of the show”, but instead focused on “strong personalities to override the mountain of trivia which pours forth”. A lot of this was down to the introduction of Australian scriptwriter Raymond Bowers, recently lauded for his work on The Power Game, and new character Bluey Trustcott, played by fellow Aussie Kenneth J Warren.

By March 1968, the initial run of the series came to an end, but Lew Grade promised it would be back after a short rest, the single hour-long episode per week set to become two half-hour episodes each week, providing more room for plotlines and fleshing out the characters. The new-style production again suffered a pre-broadcast incident that perhaps should’ve served as a warning. While the original run had been hit by a mucky book theft, the comeback series saw a much more serious incident in September 1968. A scripted explosion at the Boreham Wood set proved to have a bit more bang than expected, the blast ripping through the studio set and sending thirty members of the cast and crew running for cover.

On returning to the screens in September 1968, the rechristened Honey Lane found itself without a suitable home. While some ITV regions scheduled the new series in the peak teatime slot of 6.30pm, Londoners hoping to catch the series would need to tune in at the less-than-peak time of 4.10pm, with new London franchise holders Thames preferring to show films or episodes of The Flying Nun in that half-six slot. For whatever reason, Thames just didn’t seem to feel it deserved an evening audience – while most ITV regions broadcast episodes of Honey Lane on Christmas Eve and Boxing Day 1968, Thames left it wrapped up under the tree. Possibly buried several feet under it.

In early 1969, other ITV franchises had shifted Honey Lane to earlier slots around 4.30pm, putting it up against Play School and Jackanory on BBC-1. By now, Thames had shunted the programme into a post 11pm slot, and it didn’t take too long before other ITV regions followed suit. By March 1969, the programme had disappeared from screens entirely. Even if viewers were initially receptive to the idea of a London-set soap, it looked like it was an idea that didn’t have legs.

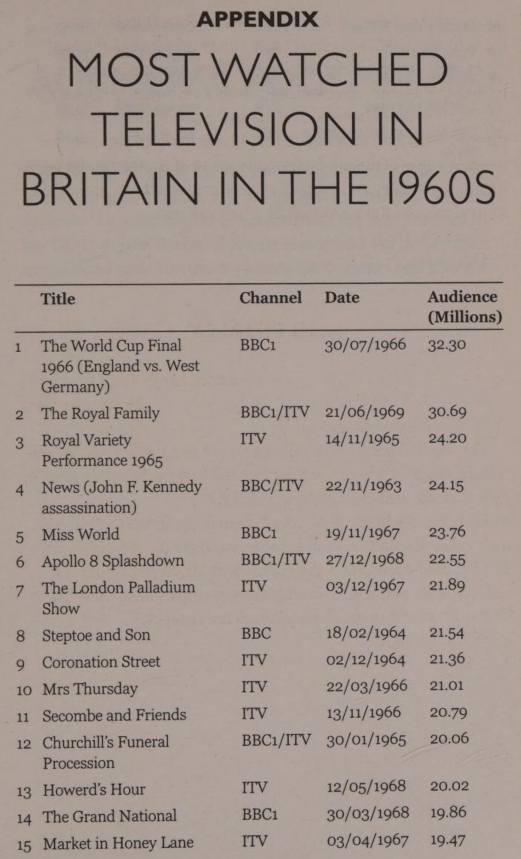

Of course, Honey Lane had initially been a success – heck, it was the fifteenth most-watched programme of the entire decade. So, if someone could pull off that trick without messing it up, maaaaybe it could work?

Whip-pan to the early 1980s, and BBC1’s weeknight schedule was in a bit of a rut. ITV were regularly pulling in viewers for Coronation Street, Crossroads and (since it moved to primetime in 1977) Emmerdale Farm, while BBC-1 found itself throwing a bunch of things at the 7pm wall hoping enough people might tune in for Ask the Family, Medical Express, Taxi or The Rockford Files to keep coming back.

Sure, some programmes in those weeknight early evening slots were reliable eyeball-grabbers such as Top of the Pops, A Question of Sport and Doctor Who, but they were only ever going to go out once per week. You’re not about to get the pop kids flocking to Middle of the Pops: This Week’s Numbers 41-75 each Tuesday. Simple solution: just do some of those soaps that ITV are doing! Problem: the programme you’ve come up with is Triangle (in joint 1484th place on the most-broadcast list with 78 showings, alongside Young Musician of the Year, Merlin and The Royal International Horse Show, if you’re wondering). Oh, if only the Beeb could find another long-running drama like The Newcomers or Z-Cars.

Step forward former Newcomers director Julia Smith and Z-Cars script editor Tony Holland.

The closest thing BBC1 had to rival ITV’s big guns was hospital drama Angels, which started in 1975, and had been running twice-weekly since September 1979. It wasn’t a bona-fide soap – it initially ran in limited series of fifty-minute episodes before moving to longer runs of 2 x 25 minute episodes each week. And – unlike Honey Lane – it didn’t immediately get dumped into hard-to-find schedule nooks.

Angels came to an end in 1983, but maybe script editor Tony Holland and producer Julia Smith had something else up their sleeves. Something original. Something that hadn’t been tried before.

Hey, how about something set in London, where several major characters ran market stalls, and which could use a standing set in spare space currently available in Elstree? Would that be a hit? Or would the mid-80s see another much-promoted serial drama series kicked to the kerb before its time?

The seeds had been sown in March 1983. Julia Smith and Tony Holland, by then working on Nerys Hughes medical cyclist drama The District Nurse, were invited to London to meet with David Reid, the BBC’s Head of Series and Serials. Beeb bigwigs had decided it was time to have another bash at a proper bi-weekly serial. It was more than a little overdue, the genre being missing from the BBC since The Doctors came to a close in 1971. And, their stock being high at the time, it was hoped that Smith and Holland were just the people to devise it.

It was a canny choice. Both Smith and Holland had been involved in TV drama since the genre was broadcast live by default, so they were well positioned to helm a serial that needed a conveyor belt of content. They were seen as reliable, their programmes delivered on time and within budget, and they’d just been involved with a series that came close to what the BBC now wanted. If everything went well, maybe their new series could even be as big a deal as Angels.

Of course, with any new programme set to run every single week of every single year, any ideas had to have legs as sturdy as Roberto Carlos and kick twice as hard. Even in its twice-weekly serial format, Angels hadn’t put out more than 33 episodes per calendar year. Their new serial would need to pump out more than a hundred. Plus, it would need a cast and crew capable of coping with such a workload.

With episodes of The District Nurse still needing to be completed, Tony Holland went back to Wales to continue writing for that series, while Julia Smith set about exploring how the new project could actually work. The hottest new property on the box at the time was Channel Four’s Brookside, which was shot entirely on location in a bespoke locale. But that was fine for a young upstart channel like Four – would a mainly studio-based approach, like Coronation Street at the time, be the safer option? Or… something in between?

A tour of the BBC regions ensued, to scope out sufficient space for both studio and outside broadcast space. Not only would both of these be needed in spades, but sufficient studio time would also be needed, along with rehearsal rooms, crew facilities, and suitable nearby accommodation for any travelling staff and artists. And could such decisions really be made when it hadn’t yet been decided what the damn thing was going to be about?

Then, fate intervened.

Over on ITV, the ATV franchise had just finished regenerating into Central, which was preparing to move into a new £21m studio complex near Nottingham. That meant the old ATV studios in Elstree in Hertfordshire were to be left doing nothing. Step forward BBC Director of Resources Michael Checkland, who sought to snap up the site for a third of the price Central were paying for their new facility. And quite a bargain it was – only 14 miles from That London, offering four large studios, loads of office space and plenty of room for facilities.

The first BBC production assigned to the new studio space: the new twice-weekly drama serial planned for BBC1. There would be no need to share space with other productions – the new programme could have sets kept permanently in place. One slight issue: there was a reason Central were so keen to leave it behind. Smith and Holland’s book on the birth of ‘Stenders refers to the scene as “like a crumbling fairground at the end of a deserted pier”.

Still, it wasn’t all bad. Several ideas for the new serial had been whittled down to just two. Such was the secrecy behind them, producer (Smith) was forbidden from sharing details of the two pilot scripts with her script editor (Holland), despite them both sharing a Cardiff flat while working on The District Nurse. As a result, she’d had to read through them in secret in bed, then hide them before breakfast each morning.

One of the ideas focused on a shopping arcade. Given the expensive technical considerations involved, that idea was rejected (though I personally like to think the ghost of Market on Honey Lane visited Julia Smith in a dream and told her not to risk it). The other idea… didn’t seem quite right either. A second writer was commissioned to prepare a different version of the script. And still, she was forbidden by bosses from sharing any details with her script editor and long-time collaborator.

Something had to give. And eventually, it did. After Tony Holland confronted Julia Smith about the curious radio silence over their huge new serial drama project, Smith insisted that she be allowed to share details with her script editor. The nod finally arriving from Them Upstairs, Smith finally shared the pilot script with Holland. His reaction: “Well, I’m not doing THAT.” Her reaction: “Good. Neither am I.”

The second idea, as it turned out, had been about a caravan park. It was an idea that hadn’t been done before, certainly. It had interesting elements, yes. But where would it go? 104 episodes each year of characters chatting outside the toilet block? Even in winter? That wasn’t going to work. Oh dear.

Then, the fickle finger of Lady Fate flicked the department head responsible for picking those two scripts out of a window (i.e. David Reid moved to a role outside the Series and Serials Department), and in came Jonathan Powell, producer of such fine fare as Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, Smiley’s People and The Barchester Chronicles. The new serial would be his first major production. But, he was very much a BBC2 type, his dramas regularly hoovering up awards and broadsheet column inches. What would he be looking for from a primetime BBC1 series?

As luck would have it, he was looking for pretty much the same thing that Smith and Holland had decided upon. Something based on contemporary working class London. But first, motions had to be gone through to ditch the caravan park idea. An exploratory visit to a caravan park ensured, and all those suspicions of unsuitability were underlined. No meeting places. Barely anyone under retirement age outside of school holiday weeks. And, in each homestead, rooms too tiny to carry out any convincing filming. All cons, no pro. One memo to Jonathan Powell later, the caravan park idea was toast.

So, on to the new idea. Smith and Holland dived into research about the East End of London, went on field trips and carried out conversations with locals of all ages. While much of the East End had started to undergo gentrification – pubs becoming cocktail bars, Citroen 2CVs parked outside stripped pine doors – their research eventually uncovered enough of the area they were looking for. Proper pubs, street markets, fly posters and residents who’d known each other for generations. But something they’d not expected was also happening – the traditional (or rather stereotypical) East End faces were joined by West Indian, Greek and Turkish Cypriot, Chinese and Indian faces. Yet the sense of community they’d known from their formative years was undimmed. No matter where someone had come from, if they lived in the East End, they were unshakeably ‘one of us’.

A pitch was quickly put together. Very quickly. The duo had returned to TV Centre at 6.15pm on 1 February 1984 only to discover – belatedly, due to the pair being on location and the limitations of 1980s communication technology – that Jonathan Powell was expecting a completed pitch to share with the Controller of BBC1 Alan Hart at 7pm that very evening. Eep.

Forty-five minutes of frenzied typing later, an outline was in place, or at the very least, on a sheet of A4.

The new serial would be in the instantly recognisable East End of London. It would feature a mix of multi-racial, larger-than-life characters. It would explore 1980s life in a disadvantaged corner of a privileged city, but where adversity can’t shake the residents solidarity. The location: a run-down Victorian Square. Some of the homes are privately-owned, some are council-owned, and many of them contain several generations of family under the same roof. There’s a pub, a launderette and a caff and a rigid sense of community spirit that won’t be rattled by whatever life throws at the residents.

While us people of Space Year 2023 know differently, Smith and Holland were downbeat about the reaction to their pitch. They’d been given almost a year to put this particular piece of homework together, and due to a series of missed messages, the impression was now being given they’d just scribbled something down on the school bus. Powell’s initial reaction on seeing the pitch hadn’t seemed especially positive, after all. Maybe they should have given the caravan park or shopping arcade ideas a little bit more credence. Or just tried to buy the rights to Honey Lane.

The following morning, Tony Holland re-typed the series pitch with some changes suggested by Jonathan Powell, to be delivered to his office at noon. But it seemed too little too late. Smith and Holland travelled to Shepherd’s Bush to deliver the revised pitch. It didn’t take long for Powell to get back to them with a decision. Usually, a decision on such a high-profile programme would take weeks, if not months to arrive from the sixth floor bigwigs of TVC. The decision on the new serial had taken just thirty minutes. Gulp.

“OK, team. You’re on!”

Well, better start getting the rest of the programme together then.

Famously, it was quite a while before the name of the programme was finalised. Much like how Monty Python’s Flying Circus could’ve ended up as Owl Stretching Time, ‘stEnders could just as easily ended up as E8, Square Dance, Round the Square or London Pride. But which to pick? All the possibilities were voted on, and a winner was chosen: East 8. Hang on, what?

A start date was in place for the series, too: January 1985, all part of a completely revamped BBC1 evening line-up. This didn’t go down well with the showrunners – to attract an audience, a new series really needed to debut as cold autumnal evenings started to keep people indoors, not in the middle of winter when people had settled on an evening TV routine. But at least that bought them some extra time. Not least to wrestle with the bureaucracy that was a large part of 1980s broadcasting, with planners, heads of departments and unions all wanting a say in how the new production was being run. Plus, the BBC purse-holders had decreed East 8 shouldn’t cost any more per episode than hospital-set Angels.

Thanks to the work of magnificently-named production associate Christopher d’Oyly John, solutions were found to operate within the BBC’s budget. Solutions were found for other stakeholder concerns, and a plan was put in place to successfully generate a full 2 x 29m30s of BBC-standard drama content every single week.

The next problem to solve was – where to use for the key outdoor set? In theory, the cheapest option was to find a suitable location in the East End of London. The buildings are already there, after all. Plus, what could be more authentic? However, that approach came with a number of issues. London isn’t exactly known for being blessed with oodles of accessible parking space for TV trucks, catering facilities and technical equipment. The travel time needed to get everyone to and from Elstree for location filming would gobble up chunks of valuable production time, and on top of everything else, the team just hadn’t been able to find any suitable real-life location for the series. The most likely contender – Fassett Square in Hackney – happened to have a huge hospital right down one side of it, and for a series trying to avoid comparison with Angels, it’d be a bit weird having characters standing in the shadow of a hospital they never mentioned.

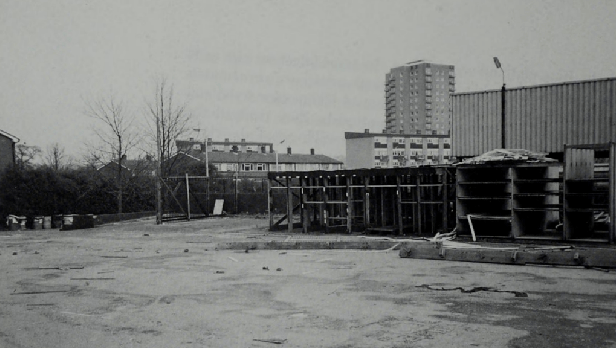

On the other hand, the Elstree studios itself had a lot of empty space. Including a great big vacant lot right behind the studio buildings. Last used for the first series of Central’s Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, the lot appropriately resembled an abandoned building site. But it also looked a hell of a lot like a solution. An bespoke external set could be built, the studio facilities were just a short walk away, and everything could now be controlled by the production team. Even the presence of a tower block in the distance just added more context to the surroundings.

Of course, there’s little point in constructing to most marvellous outside set for your programme if you’ve forgotten to add any characters or stories to it (well, unless it’s a particularly high-falutin’ BBC2 series about architecture), and so Julia Smith and Tony Holland swapped the unfolding logistical chaos of southern England for the northern Canaries, decamping to Lanzarote to try and come up with some characters and stories. Not the sunniest of places in March 1984, but far enough away from other distractions to finally focus on scripting, as evidenced by the bulk of their luggage being a typewriter and reams of paper. Their itinerary included the creation of 23 characters for the series, at least twenty storylines and a rough outline for the first few years of events in the Square.

Using Tony Holland’s family history as a template, two large multi-generational families would become the initial focus of the series: the Beales and the Fowlers. Inspiration for others was taken from their reconnaissance missions to the East End – an elderly widow with a personality as colourful as her make-up, always seen with her little be-ribboned dog in tow, an avuncular middle-aged Jewish doctor who residents turned to in times of need, a young single mother from an Irish Catholic background struggling to care for her newborn. Each new character was given layer upon layer of background, personality and a name.

Perhaps the most interesting of the new characters were Jack and Pearl Watts, landlord and -lady of the square’s pub, along with their teenage adopted daughter Tracey. Their marriage is little more than a performance put on for the regulars, the flat above the pub is the venue for the real story of their marriage – unease, duplicity and dishonesty. Jack’s a local lad made good, at least compared to his contemporaries, and runs a tight ship at the pub. He commands respect. However, Pearl’s one of the select few willing to give as good as she gets when it comes to Jack. As for Tracey, her home life is far from happy, the only real positive attention from her adopted parents coming when one of them is showering her with attention to score points over the other.

The cast of characters complete, not just a collection of personality types, but a rich interconnected community, whose lives in some cases first intertwined decades before being dreamt up. There were tweaks to be made at a later stage – Jack, Pearl and Tracey would became Den, Angie and Sharon, for example – but each potted biography led Smith and Holland towards storylines for each family, both short- and long-term.

Being able to plan several months, even years ahead even gave the co-creators space to cannily schedule key twists for parts of the year when viewing figures are likely to be higher. The plan, in short, was all coming together. By the end of their trip to the Canary Islands, Smith and Holland had loosely mapped out the first three years of key events within the Square, their initial hurried draft now fleshed out to 30,000 words of detail.

Pondering the incoming series several months later in October 1984, a piece in The Stage queried which of the two approaches for a modern serial drama could choose from. The first method is to try and reflect a range of diversity of opinion on social, political or personal issues, with the ultimate effect of getting such views into more homes than any current affairs programme could dream of. The second – avoid issues, offer some warm, comforting entertainment, offering a break from the social affairs and acting an electronic Horlicks to the audience. In short: Brookside, or Crossroads. It wasn’t hard to guess which side of the coin would be facing up when the new series finally flickered into life.

How soon to make that clear to the audience? Well, no point hanging about, or engineering an exposition-heavy argument at the pub to kickstart the first episode. Go with a bang. Or a boot.

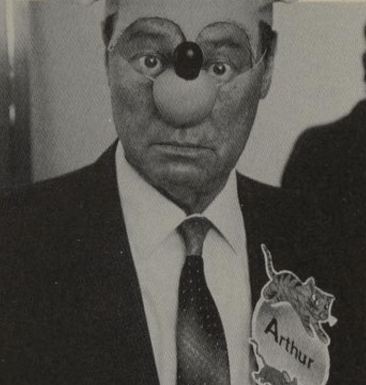

“East 8 starts with a bang, as a size ten boot kicks down a door that’s locked from the inside. The tiny, dirty and foul-smelling council-flat behind the battered door belongs to Reg Cox (known locally as “the-old-boy”, and a cantankerous bastard at the best of times) who hasn’t been seen around the square for days… Once the door’s down, three men rush into the gloomy main-room: Dan, the publican, Arthur and Ali, the Turkish Cypriot – still in his pyjamas or dressing gown. They find the old boy sitting in his favourite armchair beside the gas-fire (which isn’t on) – and he’s very nearly dead.”

Storyline for Episode One, Scene One – EastEnders: The Inside Story, Julia Smith and Tony Holland

As preparations continued, May 1984 brought an unlikely invitation from the ‘rival’ camp – Coronation Street’s Bill Podmore invited Julia Smith over to Manchester to visit the cobbled set of Granada’s long-running serial. Plus, hey, while you’re here, come and see the set of the new twice-weekly drama that we’re developing. It’s set in a market! Hang on, what? Yep, wary of East 8’s tanks on the lawns of Wetherfield, Granada were planning their very own new continuing drama. So, it was a race to air. And East 8 had yet to cast any actors.

That started to change in July, the first of three months in which the entire series would be cast. Some of the cast were sought out by Smith and Holland – first choice being Bill Treacher (following his small role as bus driver in An American Werewolf in London) (oh, and they’d worked with him on Z Cars. Mainly that, yes). Similarly, Shirley Cheriton had worked with the showrunners on Angels, and was chosen to play upwardly mobile Debbie, while writer Bill Lyons had worked with Sandy Ratcliff previously, and suggested her for the role of hardfaced minicab firm co-owner Sue Osman.

Other roles were largely cast from a multitude of auditions following bags of letters, photos and recommendations from agents. And, slowly but surely, real-life faces were finally attached to the characters punched out over that fortnight in the Canary Islands. The next pressing concern was the name of the series. The working title had been ‘East 8’, but that was never really going to stick (not least as it was actually set in the fictional postal district of E20). Eventually, those casting sessions brought about the answer – after both writing countless letters to casting agents pointing out that “only genuine East-enders need apply” for the roles, it finally hit Julia Smith that the title had been staring them in the face all along. One capitalisation-of-the-second-E a little later, thanks to the suggestion of BBC2 controller Graeme McDonald, the programme title was sorted.

September 1984 brought more bumps in the road. Scripts had been written with the aim of the series launching soon, but the programme’s lead director issued an ultimatum on the uncompromising nature of them, demanding that the characters be lightened up, to be at least a little more likeable. Smith and Holland stuck to their guns – no rewrites. Subsequently, EastEnders found itself with just two remaining directors. Another issue came from the phone of newly-installed Controller of BBC1, Michael Grade. The plan had been for the new series to make up part of BBC1’s weekday evening schedule, running for two weeknights each week while the rebooted version of Saturday night chat show Wogan ran for three. The problem was: Wogan wasn’t going to be ready for the proposed start date, so the launch of both programmes would need to be moved back a month. With EastEnders’ scripts being a very much real-time affair, with in-show Valentine’s Day happening on real-life Valentine’s Day and such… they’d have to be rewritten after all.

A key day for the series fell on 10 October 1984, which saw the cast introduced for the first time to the press, and therefore the public. At this stage, the closest many of the cast had come to each other had been when they’d happened to have been in passing where they’d been auditioned on the same day, meaning this was their first real meeting. Some of the casting decision had still to be made, some key actors were otherwise engaged with roles elsewhere, but at least the whole thing now seemed that little bit more real. This was really going to happen.

Though not for everyone.

The part of Angie Watts originally went to Jean Fennell, then mostly known for stage roles, but initially deemed a good fit for the role. However, as rehearsals went on, it was felt that she’d been miscast. Everything they needed to get from Angie just wasn’t coming through in Fennell’s performance. According to Leslie Grantham’s autobiography, the disparity between the character of Angie and Fennell’s take on it was even wider, with the actress determined to play Angie as more of a Bet Lynch figure, but in any case the now ex-Angie was given six months’ full pay, and a car home.

(For the record, the only change Grantham refers to demanding when it came to Den was that he support West Ham rather than Arsenal, resulting in a variety of Highbury-related decor swiftly being replaced in the Old Vic.)

So, with just four days until the first studio recording, one of the programme’s main characters was uncast. As fate would have it, someone who’d previously been considered for the role by Julia Smith came back into play. Initially, Smith had dismissed the idea of offering the role to her former drama school pupil Anita Dobson, feeling she was a little too young for the role. But, on being contacted by Smith, a brief audition proved that those initial concerns were unfounded – she was perfect for the role.

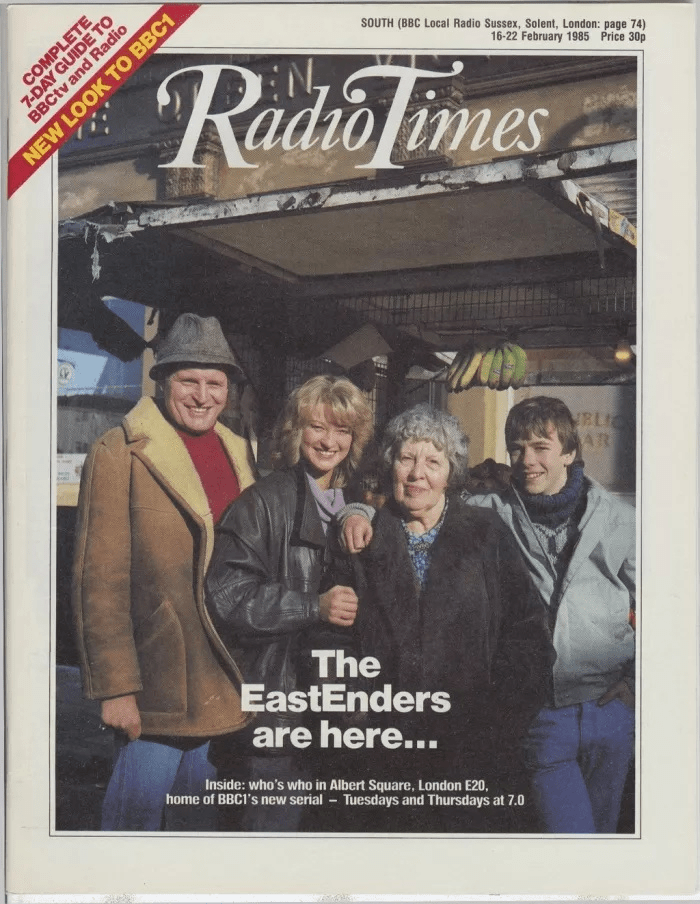

Finally, the time came for the programme to air, and it’s fair to say the BBC had a lot riding on it. Smith and Holland had been given a huge amount of autonomy over the series, with the first episodes being recorded for air without any pilot being shot, and no opportunity was given for management to view the recorded episode footage until the sole edit had been completed. One aspect of the programme that management could control regarded the Radio Times front page promoting the first episode. The wording for the famous RT front cover had initially read “The EastEnders are here… and they’re luverly!”. It took the intervention of department head Jonathan Powell to have those final three, ill-fitting words removed. Otherwise an expectant nation may well have tuned in anticipating an Only Fools and Horses spin-off.

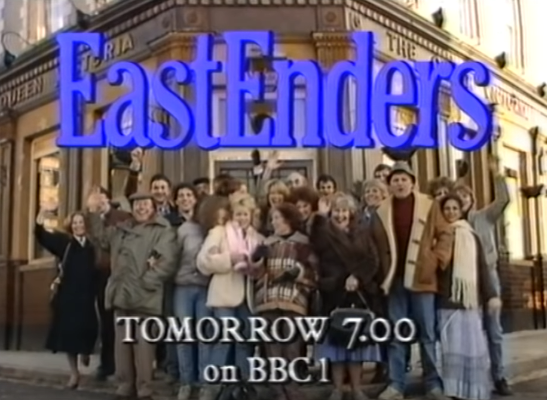

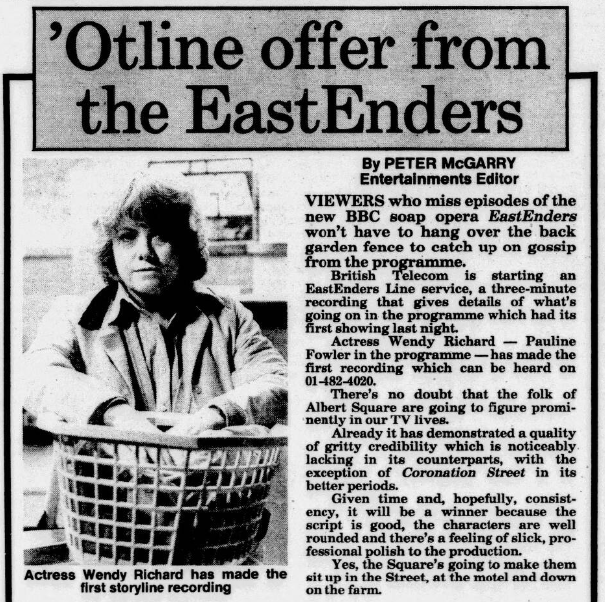

A flurry of EastEnders trailers slid between other programmes in the weeks leading up to episode one, and Michael Grade had given in to Julia Smith’s request that Sunday afternoon BBC1 play host to a weekly omnibus of episodes, so that any fans who’d been otherwise engaged on Tuesday or Thursday evenings would be able to catch-up. British Telecom even offered up an ‘EastEnders line’ number, which provided a three-minute synopsis of the previous episode, written by Tony Holland and read by a cast member.

Finally, the time had come. On Tuesday 19 February 1985 at 7pm, 17 million people tuned into to watch Den Watts kick in Reg Cox’s front door. The rest is television history.

Oh, as for Granada’s spoiler soap Albion Market – the market-based Friday/Sunday soap failed to find an audience, not helped by London franchise LWT declining to air the programme in a primetime slot. It was cancelled within a year.

Granada should probably have set it in a caravan park.

That’s right, I just did mark 36 years of a programme’s history by writing a billion words that cease a few seconds after the first episode airs. I could easily have written a lot more, but I’m keen to get this online before the BBC’s second centennary. So, until next time.

Only two more shows to go!

2 responses to ““He Might be Slightly Dodgy, But a Gooner He Ain’t” – The 3rd Most-Broadcast BBC Programme of All-Time”

Great article as always, Mark. (It was #5 in my list, but only because of those two interlopers Newsround and Newsnight.) Appreciated the reference to Albion Market – it may not have been a great soap but it had the catchiest theme tune ever!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating that the moon landing doesn’t make the top 15 of most watched telly in the 60s.

Great article – really gives a sense of how scary it must have been working on such a high profile show pre-launch.

LikeLike