Back with a pair of shows that come as close as you can imagine to the final Top Ten.

12: Flog It!

(Shown 4530 times, 2002-2021)

Waiting. There’s something that should be obsolete in this day and age. If you order something off the internet, you want it to arrive the next day. If you want to watch a film, you want to be able to stream it right away, even if you’re just looking at your phone while queuing at the deli counter in Sainsburys. And, I think I speak for us all, if you’re just had your grand-grandmother’s favourite urn valued on Antiques Roadshow and you want to cash in, you want the cash THERE and THEN. Not taking it home, sitting up all night with a baseball bat in case burglars have overheard the valuation, and carefully taking it to an antique dealer hoping to get the full promised amount. I mean, who’s got time for that? Gimme gimme gimme. Now.

Well, if you’re anything like as impatient as I am, Flog It! is the show for you. The formula is much the same as that of Antiques Roadshow – members of the Great British Public bring their heirlooms along to a picturesque location somewhere in the UK, where they might be examined and valued by a resident expert, all under the watchful gaze of host Paul Martin. The main difference is that the owners of antiques are then given the option to sell their items at auction, giving a sense of closure to the viewer and (hopefully) a pocketful of cash for the owners.

Occasionally, it takes more than mere pockets to contain the full value of items discovered by the programme. A 2013 episode filmed at Lincolnshire’s Normanby Hall saw Cleethorpes resident Ann Bromley bring in a collection of African tribal art, with resident expert Michael Baggott estimating the lot to be worth between £200-£400. That’s not too shabby, if nothing else it comfortably covers the petrol money for getting thete. Off to auction it went, only for everyone to learn this wasn’t of African origin at all. The collection, long left in a Cleethorpes wardrobe, turned out to contain a rare Australian Aboriginal shield, and was subsequently sold at auction for £30,000, having been bought by the Sydney Museum of Primitive Art.

Unlike similar programmes of that ilk (Antique Roadshow, Antiques Road Trip), what had seemed an unstoppable juggernaut finally juddered to a halt in 2020, when the programme had been cancelled to make way for more contemporary fare. However, something that huge doesn’t just come to a halt – that’s just plain physics. Indeed, we still haven’t reached the end of Flog It!’s stopping distance, at the time of typing a variety of episodes from the last few series are going out each evening on BBC Two, seven days per week. Basically, the ineffective cancellation since the latest political berk banging on about being cancelled from the comfort of their £100k/annum gig on TalkTV.

Of course, it’s not a proper long-running daytime strand unless it’s flanked by spin-off programmes, and Flog It! was no slouch there. Alongside highlight compilation show Flog It! Ten of the Best (broadcast 53 times, 2007-2009), there was Flog It! Travels Around Britain (broadcast 20 times, 2010-2016), which saw Paul Martin leave antiques behind to explore the influence of nature in art. The most successful spinoff arrived in 2013, with Flog It: Trade Secrets (broadcast 380 times, 2013-2020). This saw Paul Martin and his merry band of experts revisit the history of the parent programme, while dispensing advice on getting the best out of car boot sales and charity shops.

Nothing like playing a charity shop for a chump, eh? Oh, Paul.

11: Jackanory

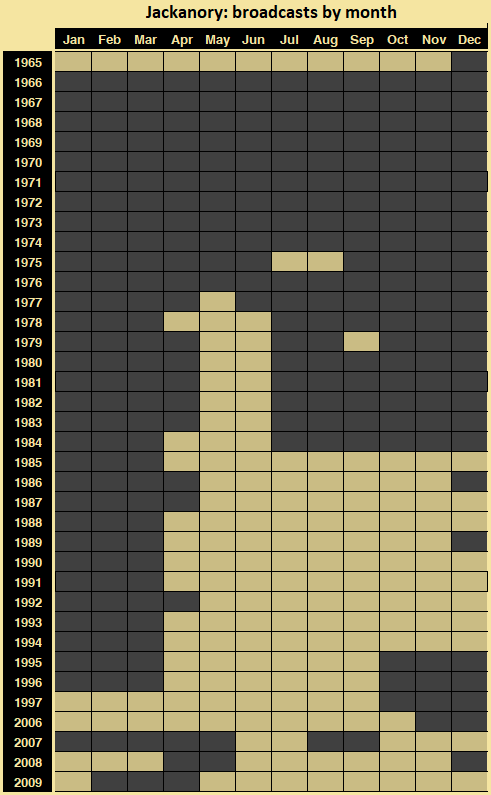

(Shown 4701 times, 1965-2009)

Some television programmes manage to generate a lot of publicity by attracting famous names to take part. Sometimes, it’s Morecambe and Wise employing the likes of Shirley Bassey, Sir Laurence Olivier, Peter Cushing and Vanessa Redgrave for high-level japery. Sometimes, it’s Shooting Stars employing the likes of Larry Hagman, Robbie Williams and Curtis Steigers for top-tier titters. And sometimes it’s Ricky Gervais getting Johnny Depp, Robert de Niro and David Bowie to be in his programmes. But there’s also a much less heralded programme that, in its pomp, attracted a guest list including (amongst hundreds of others) Judi Dench, Denholm Elliott, David Suchet, Joyce Grenfell and Ian McKellen. Oh, plus some chap now known as King Charles III.

Despite the star-studded future it would enjoy, Jackanory began under far more modest circumstances. With the BBC needing to output hours of children’s television each week, there was always a pressing need to produce content that could be worthy and captivating for the kids, but not everything could have the budget of a Blue Peter or Vision On. And so, Jackanory was born.

Since 1950, radio series Listen With Mother had proved that a premise as simple as somebody reading out children’s stories over the airwaves would provide a welcome respite for harried parents, and in the 1960s former Listen With Mother producer Joy Whitby – by now having moved to TV – wondered if such a premise could also work on screen. It was fair to say Whitby had built up a decent track record, having devised BBC2’s pre-school smash Play School, which featured a daily section where a short story was read to the audience.

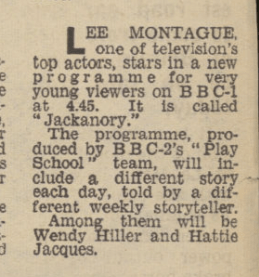

Guest readers and simple illustrations helped capture the attention of Britain’s TV tots, and so Whitby was asked to develop that idea into a standalone teatime show for older children, with a target age of 8-to-11, over on BBC1. Given a six-week trial run, Whitby added Play School producers Anna Home and Molly Cox to the ranks, with the first story (traditional fairy tale Cap of Rushes, read by actor Lee Montague) going out on Monday 13 December 1965 in the pre-Blue Peter 4.45pm slot.

The scheduling helped the new programme gather an audience, Whitby’s idea being that the timeslot would attract passing attention of adults as they returned home from work, and the involvement of mainstream actors would help keep their attention fixed firmly on the screen, sharing in the stories being read to the kids. That first six-week run also featured actors Wendy Hiller (a year before her third Oscar nomination for A Man for All Seasons) and Hattie Jacques, along with author Enid Lorimer.

The programme proved to be a instant success. As the programme neared the end of that initial six-week run, a commission came for the series to continue running throughout the year. The fact it was a relatively inexpensive premise – a welcoming narrator reads a story (or series of short stories) over the course of a week, all from the same sparse set, meant little production lead time was needed, meaning it could continue without the need to retool. But while it didn’t need the longest credit roll at the end of each episode, it also meant the programme wasn’t initially deemed worthy of a place in the BBC archive, with many editions from 1960s and 1970s being wiped shortly after transmission

Within a year of the first edition of Jackanory, the programme was deemed to be so firmly affixed to the zeitgeist, a selection of celebrity narrators were invited onto Late Night Line-Up to discuss the show. Margaret Rutherford, at that point dozens of films into her acting career, proclaimed the experience to be a fairly terrifying vocational detour, while James Robertson Justice expressed how he’d needed to rely on the more than capable guidance of producer Molly Cox to get through his initial Jackanory week.

It didn’t take long before being asked to narrate a week of Jackanory was deemed a badge of honour for actors. Luckily, being able to call on the talents of top actors proved to be a boon for the production team, with the programme’s modest budget allowing little time for outtakes, so the more adept at delivering lines a narrator was, the better. It also certainly didn’t shy from attracting faces the target audience might not be too familiar with, such as Spike Milligan, Dudley Moore and Alan Bennett (the latter, of course, seen more as a white hot satirical firebrand than the literary teddy bear he’s now regarded as [SUB: PLEASE CHECK]). It’s almost tempting to add “much to the bafflement of watching children” here, except the same was far from true a few decades later when Rik Mayall narrated George’s Marvellous Medicine. My school was certainly abuzz with excitement about it in advance, so feel free to ignore that thought.

Part of the programme’s strength was in the range of stories being relayed to its young audience. Joy Whitby saw it as her mission to introduce viewers to stories they might not ordinarily encounter. So along with classics like The Railway Children, The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse or The House at Pooh Corner, you could expect to hear retellings of folk tales from Africa, Scandanavia, India or Russia.

Contemporary stories from more modern authors were also regularly featured, and in October 1968 the doors were opened to the next generation of young authors, with a week of stories written by the winners of a ‘Write a story of Jackanory’ competition. Possibly anticipating a modest number of entries, the Jackanory team found themselves sifting through more than 6,000 entries from hopeful young scribes. From that bumper mailbag, the most popular genre of story was magic, followed by adventure and science fiction – the eventual winners being as young as four-and-a-half year old David Osrin (his story reportedly dictated to his frantically scribbling mother), and entries arrived in formats ranging from bound booklets to scribbles across their parents’ newspaper. By the end of that week, ten young storytellers found themselves in possession of a three-guinea book token and at least a term’s worth of playground bragging rights, ensuring the Jackanory Children’s Week would remain a feature for years to come.

One key part of Jackanory was that illustrations were used throughout each story. Invaluable in helping the audience feel a connection to each story (at least they were if you had an attention span like mine), and in helping differentiate the programme from radio mentor Listen With Mother, the artwork was initially created by a small team of in-house BBC graphic designers. With the programme running five days per week throughout the year, to paraphrase The Simpsons, this put a tremendous strain on the illustrator’s wrists. This meant that illustrators had to take a production line approach to working, while juggling their desire to get their best work onto the screen. Deadlines were regularly straddled as the episodes were prepared, with the team of illustrators keenly flicking through each incoming story with a mixture of excitement and despair on spotting the most thrilling-but-busy scenes within each tale. (“Ooh, a sword fight! Gah, at a lavish banquet!”)

Occasionally, the artistic licence taken with Jackanory illustrations required the involvement of the showrunner. In the splendid BBC Four documentary The Story of Jackanory, illustrator Graham McCallum tells of the time Joy Whitby had to request an illustrator nip down to the studio immediately, as a horse being featured in a pivotal scene had been drawn with a little too much, erm, front tail on show.

In the 62nd volume of literary journal Something About The Author, illustrator Gareth Floyd (above) refers to the demands that came with his twelve years on Jackanory. The production team had seen Floyd’s illustrations in children’s books and offered him a freelance gig working for the programme, having quite sensibly realised the in-house team were being stretched that bit too far. Having worked on a couple of Jackanory commissions per year, including standout stories Stig of the Dump and The Railway Children, Floyd would be expected to provide sixty pictures for a week’s worth of episodes, a process made tricker by his usual style proving unsuitable for broadcast TV (not ‘unsuitable’ in that sense, you filthy lot):”My usual style had been to draw in pen, then in colour in a sort of two-wash drawing. That technique presented a problem on television where you tend to get a strobing of lines, the effect of lines crossing, [so] a more painterly style is often more suitable for television illustrations.”

The relentless demand for fresh artwork being piped through to the studio proved too much for some, as Floyd recalled: “It’s not easy to finish sixty pictures on a tight schedule, and you can’t be late with material for television. Once the drawings were done I had to go to the studios and spend about three days altering details. I had heard many stories of illustrators who couldn’t take the strain. The producer would have to finish the drawings because the artist was too traumatised to go on.”

Not all Jackanory illustrators would feel that much strain, however. It’s probably safe to say the most well-known of the freelance illu strators to work on the programme was Quentin Blake, who took a quite different view. Speaking in The Story of Jackanory, Blake recalls how he used to think “they’re only going to see this for several seconds! Whoopee!”

Not that his near-minimalist style was unsuited to the show, of course. The energy, character and sheer joy contained within each Blake scribble brightened any episode to feature them. Little surprise that he’d work on more than 150 episodes of the series. Slightly more surprising that Blake would go on to present several episodes of the series in the 1970s, drawing illustrations for the Adventures of Lester stories as he went. The need to be constantly facing his canvas meant that, unlike most of the presenters on the programme, Blake would need to remember his stories word-by-word rather than read them from autocue. So it’s probably fortunate that Blake had written all the original Lester stories himself.

Back with the traditional setup, there were two sets of steady hands that kept the ‘Nory stable more often than any other: Bernard Cribbins – who’d go on to host the charming CBeebies pseduo-‘Nory Old Jack’s Boat until 2015 – and Kenneth Williams. With the latter, Williams’ distinctive performance as half of Round the Horne’s Julian and Sandy brought him to the attention of director Jeremy Swan, who approached Anna Home about getting him to take a turn as presenter. On receiving the offer, Williams expressed concern over the role, almost turning it down, having been informed he’d need to wear a huge hat bearing the illuminated legend ‘Jackanory’ throughout each recording – a particularly cheeky fib relayed to him by a mischievous Hattie Jacques. Fortunately for a generation of kids, Williams’ fears were allayed, and his marvellous vocal mannerisms would go on to feature in a total of 69 ‘Nory episodes.

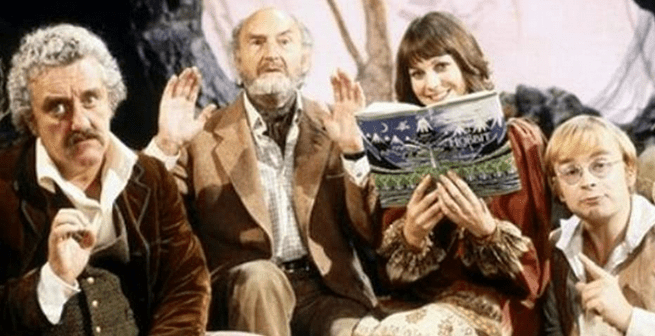

Such was the popularity of the programme, the brand was extended to cover full-on dramatic stagings of stories in spinoff Jackanory Playhouse – twenty-five minute programmes with full casts – running between 1972 and 1980. This helped whet the BBC’s appetite for producing more proper drama programmes within the Children’s Television hours (rather than standalone family dramas placed elsewhere in the schedule), some of which would be adapted from stories previously read in (standard) episodes of Jackanory, such as Jonny Briggs (Jackanory 1977-1984, standalone programme 1985-1987) or The Borrowers (Jackanory 1967 and 1983, standalone series 1992). Sadly though, it would be the growing popularity of standalone drama series that spelled the beginning of the end of Jackanory.

By the mid-1980s, with Children’s BBC putting out a range of pre-recorded drama ranging from The Box of Delights to Grange Hill, the promise of a bejumpered Martin Jarvis reading tales from a sitting room seemed a little less essential, and having started taking summers off in the late 1970s, from 1985 Jackanory was a treat served only during the first few months of each year.

That didn’t mean the programme was going without a fight, however. The introduction of more contemporary storytellers such as Rik Mayall (George’s Marvellous Medicine in 1986 and The Fwog Pwince – the Twuth! in 1993, Jack and the Beanstalk on Christmas Eve 1995) or a pre-Marion Tony Robinson (Theseus the Hero in 1985 – adapted by Richard Curtis and Robinson, Odysseus in 1986, Terry Jones’ Nicobobinus in 1988, and Skulduggery in 1993). Robinson’s stories took to location filming, often involving members of the public, which definitely provided a fresh energy to the series.

Series producer Angela Beeching remarked in The Story of Jackanory that Mayall’s episode had been the popular week of Jackanory in the programme’s history, and (predictably) one of the most complained about1. Oh, 1980s parents. Little wonder that Rik’s inaugural week of Jackanory would be repeated on Children’s BBC in 1988, again in 1994. Plus, once the original audience was somewhat older, again on BBC Four in 2006.

In 1990, the programme’s 25th anniversary was marked by a series of greatest hits, with some of the most popular Jackanory narrators (Patricia Routledge, Bernard Cribbins, Tony Robinson) reading stories by some of the nation’s favourite Jackanory story authors (Joan Aiken, Helen Cresswell and, ah, Tony Robinson). However, the victory lap did little to disguise falling viewing figures. From a 1970s peak of five million viewers, the early 1990s saw audiences averaging around two million (yes, that’s a lot nowadays, but shush). The number of episodes airing in the weekday CBBC strand fell from 64 to 48 episodes per year between 1992 and 1993.

A new producer, Nel Romano, joined the series in 1993, and attempted to bring the storied programme a little more up to date without losing that key identity. In a world with many more distractions to compete with, something new was needed to distract kids from switching to their SNES on AV2. In came another injection of energy, with narrators more normally seen after the watershed like Adrian Edmondson (Diana Hendry’s Harvey Angell, 1993), Kathy Burke (Roald Dahl’s The Twits, 1995) and Paul Merton (Morris Gleitzman’s Misery Guts, 1993). The intent was clearly to make clear how cosy old Jackanory was now anything but. Sadly, the move did little to increase viewing figures and on Friday 31 March 1995, Jackanory aired for the last time in a weekday CBBC slot, returning that October in a Sunday morning slot on BBC2, where stories would be delivered in a single, longer programme.

That new home for the programme started with a determined effort to make the most of things, the first episode of the series marking thirty years on air by bringing back Bernard Cribbins for a tribute to fellow ‘Nory favourite Roald Dahl. Subsequent episodes would see contemporary figures like Pauline Quirke, Mike McShane and Diane-Louise Jordan take to the storybook. Despite those efforts, the early start needed to catch Jackanory meant that viewing figures continued to decline, and in 1996 the original Jackanory was given the chop.

To close things off on Sunday 24 March that year, in came a classic pairing: Alan Bennett and Winnie the Pooh, a duet originally performed in a 1968 episode of the programme.

That wasn’t quite the end for the series, however.

The Sunday morning BBC2 slot was handed over to a run of Jackanory Gold from October 1996, starting with Arthur Lowe reading Peter Hughes’ The Emperor’s Oblong Pancake from 1976. That run would last until December 1997, but Jackanory’s legacy continue for years to come.

Cue the new BBC channels, with Choice and Knowledge being hungry binary beasts desperate for content. It was BBC Knowledge that took up repeat runs of classic Jackanory from 2001, and better yet, in 2006 a fresh batch of Jackanories arrived on the new standalone CBBC channel, with taster episodes also going out on BBC One. The new episodes were perhaps now more at home on a channel with more modest expectations for viewing figures, but it was only ever a short-term concern.

More success was made of another spinoff, with Jackanory Junior airing on CBeebies (and the CBeebies morning strand on BBC2). Stars such as Lenny Henry, Martin Clunes and Art Malik delivered a combination of stories old and new, keeping the Jackanory brand on the main BBC channels until 2009.

From there, the Jackanory name faded into the background, with early morning Jackanory eventually morphing into the early evening CBeebies Bedtime Stories, with one-off five minute tales delivered by a variety of famous faces right before the channel bids sleepy-bye to the digital multiplexes for the night. And, given the fragmentation of viewers across the digital landscape, it’s a format that remains resolutely popular. The stories are still interesting enough to command attention, and with famous names ranging from Tom Hardy to Dave Grohl on hand to read them, it’s every bit as big with parents as the little ones.

It might not quite match the full-on energy of George’s Marvellous Medicine, but it all brings in nicely back to the simpler original age of Listen With Mother on The Light Programme.

That was quite a long one, wasn’t it? And so, we’re at the end of the 100-11 part of the list. Yikes. Come back soon for the start of the ULTIMATE TOP TEN.

- Not that this was the only instance of innocent old Jackanory receiving complaints. The retelling of Ted Hughes’ The Iron Woman in 1994 draw complaints for the accompanying model footage, while a much earlier episode referring to Walter Raleigh being sent to ‘The Bloody Tower’ (i.e. Tower of London) compelled at least a few angry parents to call the BBC Duty Office at the shocking use of swearing on kids’ TV. ↩︎

6 responses to “The 100 Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes Of All Time (12 and 11)”

I’m looking forward to reaching the Top 10 next time. For a while now I’ve been keeping a list of what I’m fairly sure will appear on the unrevealed part of the list, and I now have only 9 programmes left on my list, of which one might be deemed ineligible for stretching the definition of what counts as a proper programme, and another might also be deemed ineligible for being too ‘newsy’ to count, so I may only have 7 of the actual 10 predicted.

The other thing I have been doing as the list unfolded is tracking the debut years of all the entries. 1965 and 2002 are now in the joint lead with 5 shows each, and only 46 of the 81 possible years (1936-39 and 1945-2021) even have one show listed, so I wonder if it would be an interesting diversion before we get to the number one to reveal the most broadcast show from each of the unrepresented debut years (if you have enough data for that) as I think it’d be interesting to see if the unrepresented years had close contenders that narrowly missed the list or else were merely fallow periods when everything Auntie tried failed rapidly.

LikeLike

I’ve also been keeping a list of what I thought would come up ,and I have a possible twelve left. There are nine that I’m pretty certain about (including two generic sports titles) and three I’m unsure about, two of which are “news” titles and one of which may be ineligible (possibly the same one as you had). Might be interesting to compare notes!

LikeLike

Yes, it would definitely be interesting to compare notes, though maybe we need to go off-site so we don’t spoil the countdown too much for everyone else. I’ve posted my facebook profile link here: https://www.facebook.com/daniel.webb.334839

if that’s any good to you, or else I’m open to suggestion for another contact method.

I don’t have any generic sports titles in my list of 9, and if I rule out the ‘not really a programme’ one from my list, but keep in the ‘too newsy’ one, then add whatever your two ‘generic sport’ one are that could perhaps end up being the true Top 10. I’m also wondering if my ‘not really a programme’ one is one of your two ‘news’ ones, although what I’m thinking of had content a little broader than just news.

LikeLike

I’m not on Facebook but here’s the list of predictions that I made for the top 28. (Anyone wanting to avoid spoilers should not click on the link.)

https://guys-diary.blogspot.com/2023/07/predictions-for-remaining-entries.html

The ones in bold I’m reasonably sure about, the ones in italics are uncertain, the ones in normal type have already gone, and the one with a line through it shouldn’t have been included in the first place!

LikeLike

You’re doing better than me! I need to go through the full list and think some more about what’s not there.

LikeLike

[…] Flog It!(Shown 4531 times, […]

LikeLike