Into the fifty! And on the BBC’s actual 100th birthday too. Would’ve been nice to have wrapped up the whole list by this point, admittedly. But at least we’re in the top half of the table now. And into the next section of the list we go.

50: Racing

(Shown 1741 times, 1946-2014)

Here’s something that’s easy to sum up in a few paragraphs: all of horse racing on the BBC since 1946.

It’s certainly a little curious that, of all the different types of racing that have been televised since that inaugural broadcast from Ally Pally, it’s horse racing that has become synonymous with the phrase ‘Racing’ on TV. Not motor racing, cycle racing or greyhound racing. It’s the equine kind that the phrase has been reserved for. And this makes it slightly surprising that it took quite a while for horse racing – literally the sport of kings – to start making any appearance within the BBC-tv schedules.

The first programme covering any kind of racing seems to have come on 9 October 1937, with ‘Road Race for the Imperial Trophy’, billed as “the first International Road Race in London (by courtesy of the Road Racing Club), on the Crystal Palace Road Racing Circuit (conditions permitting)”. Such was the clamour for the live news of the motoring event, it resulted in the Television Service opening up earlier than usual, at a still-leisurely 2.25pm rather than the usual 3pm. Britain’s sole TV channel kept tabs on the race through to 5pm that Saturday, occasionally opting out for key programmes such as ‘In Our Garden’, ‘First Time Here’ and ‘Punch and Judy with P. F. Tickner’. One can only hope the conditions were indeed permitting, because any postponement would have required a lot of filling for the nascent service.

The next instance I can find of televised racing of any kind came almost a year later, on 8 October 1938, this time under the more helpful billing of “Motor Racing” (so I don’t have to look up details of an event from 85 years ago to check whether it’s cycles or cars, unlike with the previous paragraph). This came with the promise of getting to see a thrilling encounter between Arthur Dobson and the presumably pseudonymous “B.Bira” in an event big enough to be advertised in national newspapers.

[UPDATE 20 OCT: Reader Jamie Bird adds some more exciting context to the above: “‘B.Bira’ who raced in the 8th October 1938 motor race, was the Prince of Siam, his full name being Prince Birabongse Bhanudej Bhanubandh (no wonder RT used his pseudonym). He raced all the way up to Grand Prix and Le Mans level and after retiring in the mid-fifties, took up competitive sailing, competing in four summer Olympics up to Munich ’72.”. That immediately makes this update at least 17% more interesting, so cheers Jamie!]

And, at least as far as I’ve been able to find, if you wanted to see any kind of racing action on your screens, motor racing was largely all you were going to see until the post-war years. Not that horse racing wasn’t covered at all, mind. It was, just in a slightly unusual way.

The Television Service listings for 2 June 1937 show The Derby being covered, but the limitations of camera technology at the time certainly wouldn’t have permitting a cameraman to scoot along after the action. So instead, viewers would hear audio-only coverage of the race, as broadcast on the National programme. On top of that, a plan of the racecourse was shown on-screen, along with “still photographs of scenes connected to the race will be accompanied with a commentary”. Lovely stuff. Curiously though, the Radio Times listing for the event claims this approach was “a repetition of the successful experiment carried out on the occasion of the Grand National”, but looking at the Radio Times schedule on the day of that year’s National, there was no such billing. So, presumably, any such coverage was done ‘off the hoof’ (horse reference).

Anyway, fast forward to 1946, and the reopened Television Service is now in a position to start covering horse racing properly. Television had certainly picked a suitably special occasion to cover. The two-mile King George VI Stakes is a racing event at Ascot that continues to this day, and BBC cameras were present for the very first ‘Stakes race in 1946. Or rather, ‘BBC Camera’ – the practice of mounting a camera to a vehicle capable of keeping up with racehorses still hadn’t come to fruition, and so a single BBC camera was affixed to the roof of the main stand, just to the right of the clock tower.

With this new practice proving a success, horse racing returned the following spring, with two days of live coverage of the National Hunt at Sandown Park. By 1948, it was a regular practice, offering home viewers a chance to roar on their favourite from the comfort of their own home without needing to decipher the rantings of a radio commentator (though I’ll wager the picture quality on those early sets didn’t make it abundantly clear which horse was which).

As the broadcast history table below confirms, horse racing would become an absolute mainstay of BBC Sport coverage for several more decades, but the frequency of races covered would fall as the nation entered the second decade of the 21st century. This decline in coverage came to a (horse’s) head in January 2013, when an exclusive contract between Channel 4 and the Racecourse Media Group started, resulting in all terrestrial British horse racing coverage moving to Four.

The table below doesn’t quite accurately convey the true extent of racing coverage on the Beeb – for many years, a large amount of the BBC’s racing coverage found itself covered within the Grandstand umbrella, and at other times racing shared a billing with up to three other sports in the TV listings. I’ve not included such instances in the totals, as that would only complicate matters. I make it about 237 instances of ‘Racing’ sharing a billing with other sports like this, if you want to amend the total yourself.

49: Points of View

(Shown 1753 times, 1961-2021)

Dear Sir, I object strongly to the letters on your programme. They are clearly not written by the general public and are merely included for a cheap laugh. Yours sincerely etc., William Knickers.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus, episode 1.11 “The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Goes to the Bathroom”, TX: 28 December 1969

A long-running ten-minute (or thereabouts) programme that has managed to clock up a surprising number of tropes for a show situated (for the most part) in a small presentation suite and shown after the end of Something American. If anyone from Panini is reading this and wants to put together a sticker collection of Points Of View tropes, start with the following:

- Why oh why oh why oh why oh*

- Them Upstairs

- Mrs Edna Surname of Dorset Writes

- Terry’s Bulge That Time

Okay, there aren’t that many. Let’s do this properly (unless anyone wants to add any more in the comments).

(*Spells, of course, yoyoyoyo)

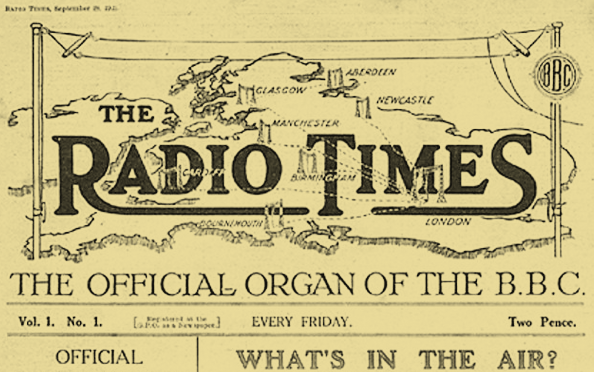

In the early days of broadcasting, if you wanted to get your opinion heard about a television programme, your main outlet for viewer dissent (or heck, praise) would be the Radio Times letters page. But wouldn’t it be better if you could have your letter read out loud by a voiceover artiste in the gap between Dynasty and The News? More importantly, wouldn’t it be handy if there was a cheap programme that could be slotted into the ten-minute gap between Dynasty and The News?

That’s where Points of View came in. Offering a voice to the viewer, and holding the Beeb to at least a little bit of account. Originally hosted by Robert Robinson in 1961, going out in the teatime gap between the end of the regional news and the start of the evening’s entertainment programming.

From there, the programme rapidly became a schedule staple, to the extent that it actually aired twice per week from 1962 – once at teatime on Mondays, then again just before 10pm on Wednesdays. The latter seems to have been at least occasionally billed as “a further look at points from this week’s post”, so it’s tempting to assume that this post-watershed slot contained pure unfettered vitriol about the scheduling of last week’s episode of Play Your Hunch, rather than a straight repeat.

By the early 1970s, either the programme proved much less popular, or there was a national drought of opinion about television (or more likely the schedules threw up fewer likely spots for the series), meaning Points Of View entered an eight-year hiatus. On it’s return however, we definitely entered the imperial phase of Points of View, with comedian, writer and presenter Barry Took taking the hot seat.

The quietly wry Took was no stranger to squeezing the most out of raw materials, having spent much of the 60s and 70s helping shape the British comedy industry having worked closely with Marty Feldman, brought together the Monty Python team, helped set up The Goodies, and became Head of Light Entertainment for LWT. And it was his winsome charm that helped make Points of View something I seldom missed as a child with a fascination of all things television.

Following Took’s departure in 1986 (and PoV having a brief flirtation with guest presenters), Anne Robinson took the reins. Then a world away from the fairly annoying Ice Maiden character she’d adopt for The Weakest Link, Robinson took on the role of people’s champion as host of the programme, on the side of the viewers against those fusty suits upstairs who just didn’t realise what the people truly wanted to see. Robinson certainly made sense in that role, her early appearances on the Beeb had been as occasional TV reviewer for Breakfast Time, and during her earlier career at the Daily Mirror she’s developed a knack of expressing relatable points in a succinct manner.

Following Anne Robinson’s departure from the series, there were short-term tenures in the presenter’s chair for Carol Vorderman and Des Lynam before Lord Terence of Woganshire took on the role of Viewer’s Champion. By this point, the programme was coming from a much less pokey environment, now in a plusher place replete with flowers and a writing desk.

Following Tel’s departure, Jeremy Vine took over from 2008 to 2018, with Tina Daheley currently hosting the series, but let’s be honest. With a multitude of other ways to express opinions on #CurrentTelly it’s a programme that seems incredibly anachronistic in this day and age. Sure, you could argue that at least having your views expressed on air (not least now the format is closer to Channel 4’s old Right To Reply) adds legitimacy to the series, but I’m going to counter with the fact that, around the end of the noughties, in an effect to move with the digital cyber-times, the series accepted comments submitted via the programme’s online messageboard. Where, instead of square old ‘names’ and ‘locations’, people could express comments under their wacky online handles, like ‘Pancho Wilkins’, ‘Colonel Geewhizz’ or ‘Alan997’.

So much for legitimacy, eh?

(Shown 1762 times, 1979-2021)

As we’ve seen at several points on the list thus far, some formats – as popular as they might be – have a very definitive shelf-life. Call My Bluff had a hardy premise, but despite the occasional revamp and recasting, came to a natural end in 2005. Sportsnight seemed to be a never-ending format, midweek sport wasn’t about to go away, but the Beeb’s capacity to cover it faded and it came to an end in 1997. And yet, a similarly simple premise, people bringing antiques to a venue where an expert tells them how much they’re worth, is one that – at least at the time of writing – seems utterly inexhaustible.

It’s a format that has proved hardy enough for a number of slightly surprising pop-culture references. The Smell of Reeves and Mortimer did a memorable pastiche of the series, with experts passing judgement on Prince’s wardrobe, booze f’ baby and host ‘Hugh Scully’ gradually getting nudged out of frame by stuffed monkeys during his links. The Royle Family centred an entire episode on the titular family using a broadcast of ‘Roadshow to place bets on the values of each antique. And, perhaps not quite as fondly remembered, the film adaptation of Tom Clancy novel The Sum of All Fears saw arms dealer and main baddy Olsen (Colm Feore) enjoy some downtime from his nuke-procuring day job by watching the series.

With such a gentle format, it’s slightly surprising to realise that the series didn’t start until as late as 1979. I’d certainly assumed it was something that had been around since much earlier, at least the early 1970s, but no. Arriving in Spring 1979 for a run of eight episodes on early Sunday evenings, it now seems a little odd that the premise even needs to be explained to viewers, such is the familiarity it now has. But, readers of the Radio Times were coaxed toward the new series with the following:

Arthur Negus goes on the road with a team of experts from Britain’s leading auction houses. They meet the public informally and discuss the treasured possessions brought along for their assessment. The result is a programme filled with surprises and excitement as people discover the truth about objects that have, sometimes, been gathering dust for years. Perhaps the biggest surprise is that there are more finds than disappointments.

– Listing for the first episode, Radio Times Issue 2884, 17 February 1979

From there, it went on to conquer the world, or at least Sunday evenings on BBC1. The presenters may have changed since those early days – Bruce Parker and Angela Rippon (1979), Arthur Negus (1979–1983), Hugh Scully (1981–2000), Michael Aspel (2000–2007) and Fiona Bruce (since 2008) – but the premise remains as resolute as ever. And to be fair, even for those who couldn’t give a jot about antiques, the Roadshow at least offers up to opportunity to share in the delight of attendees learning the trinkets from their attic are unexpectedly worth a five-figure sum, or even offering a chance to enjoy the schadenfreude of someone learning that Great Uncle Albert’s Victorian military figurines were actually cheap post-war replicas.

The programme would even lead to a number of spin-offs and specials, including the following:

Antiques Roadshow Gems (broadcast 1990-1992), More Antiques Roadshow Gems (1996-1997)

Hugh Scully introduces repackaged highlights from the programme, each fifteen-minute episode focusing on a particular type of antique.

Priceless Antiques Roadshow (2009-2017)

While the former highlights packages were fairly lightweight daytime filler, Priceless took things to the [puts on Oakley shades and backwards Limp Bizkit hat] extreme. Going out at 6.30pm weeknights on BBC Two, Fiona Bruce recalls some of the most memorable moments from past editions of the show, initially joined by former host Hugh Scully to look at some of the most expensive objects ever seen by the experts.

Antiques Roadshow Detectives (2015)

To the slight disappointment of anyone hoping for a Baywatch Nights-style spin-off, Detectives saw Fiona Bruce join AR experts to explore the oft-interesting backstories behind heirlooms valued by the Roadshow.

Antiques Roadshow Going Live! (1991)

A perhaps unlikely addition to the BBC1 Boxing Day schedule for 1991, this was breathlessly billed as “the first Antiques Roadshow for youngsters”, with Hugh Scully joined by Phillip Schofield, Sarah Greene and (of course) Gordon the Gopher. In this special, the AR experts assembled at Bristol’s Temple Meads Station to pass their judgemental eye over trinkets from train sets to Thunderbirds toys.

The whole affair came after a surprisingly popular appearance on Going Live! by Scully and expert Hilary Kay, with series producer Cathy Gilbey remarking on the deluge of phone calls from viewers asking if their belongings might be worth much.

Antiikkia, Antiikkia (1997-)

Because Britain isn’t the only country containing old things, the Antiques Roadshow format has been adapted around the world. Versions of the series have appeared in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden and the USA. And also Finland, where YLE TV1’s Antiikkia, Antiikkia has been running since 1997. That version was such an instant success, within a year comedy series Komediateatteri Arenan (Comedy Theatre Arena) was putting out a parody of the series where worthless tat was brought in for valuation, and the sole item of value met a sticky end.

47: Arthur

(Shown 1777 times, 1997-2012)

Well, after four not-a-surprise-to-see-that-here entries, one that’s very much out of left-field. On seeing this name burble out of the BrokenTV dot matrix after barking ‘print results’ into the attached microphone, I genuinely expected it to belong to a number of distinctly different shows. A series of one-man playlets starring Arthur Lowe? Maybe. A long-running CBS sitcom vehicle for Bea Arthur? Very likely. A long-running Saturday evening dance extravaganza in the Wayne Sleep mould starring Arthur Negus? As good a premise as any. I mean, no way on earth can this solely refer to that American-Canadian cartoon about an anthropomorphic aardvark that doesn’t look like an aardvark.

Reader, it does solely refer to that American-Canadian cartoon about an anthropomorphic aardvark that doesn’t look like an aardvark.

Maybe I’m just out of touch, or from the wrong generation, because while I was aware of the animated series Arthur, mainly from adverts for the show on Nickelodeon in the days of pre-digital Sky. In fact, it’s so far off my radar that when it recently started airing on CBeebies, I just assumed it was a rebooted series. It’s only in looking at an episode guide to write this that I learn no, Arthur has been running continuously for 25 years. That’s 253 episodes in total. And, as fate would have it, it has only just wrapped up for good, with the final episode debuting on PBS Kids on 21 February 2022. That’s long enough for the title character to have been voiced by as many as nine different actors, and by the time of that final episode it was considered the longest-running children’s animated show in US TV history.

In short: yes, I am out of touch.

The series itself is based on the ‘Arthur’ series of books by Marc Brown, first published in 1976, and (along with the TV adaptation) helps a young audience understand issues they may experience in their formative years, including weightier topics like dyslexia, cancer, diabetes and autism. The action centres on 8-year-old Elwood City resident Arthur Timothy Read as he makes his way through family life as the oldest of three siblings in the Read household, and through school life as part of Mr Ratburn’s third grade class. Given the sheer number of episodes, it’s not a huge surprise there are practically hundreds of supporting characters, but stand-out regulars include Arthur’s younger sisters DW and Kate, plus pals Buster (a white asthmatic rabbit and Arthur’s bestie), Francine (a sports-obsessed monkey schoolgirl) and Alan (a bear schoolboy of Senegalese descent).

The pilot episode of Arthur, broadcast in 1993, seems to take a decidedly different take on the original books, mind you. In these, the action focuses on what seems to be a much older version of Arthur, he’s suddenly a human being rather than an anthropomorphic aardvark, he’s battling alcoholism and he’s being played by, of all people, Dudley Moore. Oh, hang on. Damn. [SOUND OF FRANTIC DATABASE EDITING]

Right, that’s five ‘episodes’ chopped off the total, then. That’ll save people having to tweet me. The real first episode of Arthur to air on British screens arrived in 1997, with the decidedly modest RT summary of “Adventures of a young aardvark”. Initially serving as the buffer between pre-school Playdays at 3:35pm and the not-quite-as-preschool comedy drama ‘Julia Jekyll and Harriet Hyde’ at 4:20pm, Arthur went out each Tuesday at 3:55pm from April to June that year, before returning to the same slot between September and December the same year. And that’s the position it held, with the occasional morning appearance during Christmas holidays. That’s until 2005, when it became a key part of BBC2’s early morning CBBC strand. Indeed, that’s where the bulk of Arthur’s appearances have been between then and CBBC’s big move away from BBCs One and Two in 2012 – accounting for 756 episodes of the show’s total. That’s a very impressive run, but will any other children’s programmes from that spell make it to our list? You’ll have to wait and see.

Personally, I’m just glad I realised in time that Arthur (the film) and Arthur (the series) are two very distinctly different properties.

46: Film [xx] (The Film Programme)

(Shown 1873 times, 1971-2018)

You know, as in Film 88, Film 89, Film 90… I mean, I could go on.

So, who was the first host of Film XX? A few things to note: the programme was originally only shown in the London region, it started in 1971, and if it was the person in the photo above this text it wouldn’t be much of a question.

Indeed, the inaugural host of what would become the BBC’s flagship film programme, was actually journalist-turned-novelist Jacky Gillott.

Jacky Gillott’s career started in newspaper journalism, but soon moved toward broadcast journalism, becoming ITN’s first female reporter.

She’d later give up reporting to concentrate on a literary career, with ‘Salvage’, the first of thirty novels to be written by her, published in 1968. Aside from novels, she’d continue to contribute written work to publications such as the Sunday Telegraph, Cosmopolitan and a role as regular book reviewer for The Times. With this in mind, she was chosen to cast her critical eye on cinema for the initial six-episode run of the BBC’s new series, and she would go on to return as host several times throughout the next few years.

In addition to fronting each episode of Film 71, she was a regular on Radio 4 art programme Kaleidoscope, as well as the station’s Any Questions? and Woman’s Hour. She’d also go on to make several appearances in Call My Bluff and book discussion programme Read All About It. Sadly, Gillott’s storied career was offset by back pain, insomnia and deep depression. She went on to take her own life in September 1980, a few days shy of her 41st birthday. After her passing, her former newspapers The Times and Telegraph printed thoughtful eulogies celebrating her warm, thoughtful and witty personality. A story sadly ending many chapters too soon.

Following the programme’s initial run, Film 71 returned in January 1972 (craftily retitled ‘Film 72’), with initial episodes hosted by a rotating line-up of hosts, starting with (a theme developing here) journalist-turned-writer (and subsequent long-time Cosmo agony aunt) Irma Kurtz.

From the sixth episode of the series, a new host took to the Film 72 chair: the one who would be most closely associated with the role for the next 27 years. That episode of the series saw Barry Norman (for it is he) carry out an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, director of the Last Picture Show, and cast his critical eye over Elizabeth Taylor and Michael Caine film Zee and Co. Still only airing in That London, the host’s seat for Film 72 was very much a hot one, with other hosts such as Joan Bakewell and Frederic Raphael also taking a turn, but it was Barry Norman who’d get to host the first edition of the show following an Oscar night, and get to chat with some of the lucky winners.

Before his stint as the BBC’s one-man Rotten Tomatoes, Norman had embarked on a journalism career that led him from The Kensington News through jobs at The Star in South Africa and Rhodesia’s Herald, then back to the UK for roles as gossip columnist for the Daily Sketch, showbusiness editor for the Daily Mail, and penning columns for The Observer and Guardian.

Our Barry didn’t just express himself journalistically. In amongst his newspaper endeavours, he found time to write a number of novels, including his third, ‘End Product’, set in a grotesque future dystopia where apartheid spread far beyond South Africa, and where new depths of inhuman cruelty become commonplace. A satire so biting readers should probably check it hasn’t drawn blood, it clearly being inspired by Norman’s spell covering events in South Africa and Rhodesia. More information on the book can be found at Ransom Note. Not a piece to be read while eating lunch, mind.

So, having proved himself to be something of the critical polyglot, Barry Norman joined the rotating line-up for the BBC’s new film review series. It was a good fit. Norman’s father Leslie Norman had worked as a film director, with an oeuvre stretching from social drama (1961’s ‘Spare the Rod’) to B-movie sci-fi (1956’s ‘X the Unknown’) and several points in between. Barry himself had taken to television with appearances on Late Night Line-Up, and proved to be every bit as pithy in person as in print.

Not that he’d be restricted to covering cinema once his feet were under the metaphorical Film XX desk (unless in some years they actually had a literal desk, I’ve not checked). Barry Norman would go on to present episodes of Omnibus, several one-off documentary series for the BBC and ITV, and along with Elton Welsby, serve as main anchor for Channel 4’s coverage of the 1988 Summer Olympic Games.

Aside from TV work, Norman could also be heard regularly on Radio 4, presenting Today, being the original chairman of The News Quiz, hosting travel series Going Places and even fronting early 1980s home computer series The Chip Shop. But, Film XX would be the programme most closely-associated with him. He would go on to host the series until 1998, when the big bucks of BSkyB finally coaxed him away from the BBC.

As a result, from Film ’99 onwards, Jonathan Ross held the presenting baton. Having previously helmed a number of shows on cult cinema for Channel 4 (including The Incredibly Strange Film Show, Jonathan Ross Presents for One Week Only and Mondo Rosso), having mainstream TV presenter Ross take up the gig was much more sensible than it may initially have seemed. He’d go on to hold the role until 2010.

From 2010 onwards, the hosting gig passed to Claudia Winkleman, who had hosted Sky’s live coverage of the Academy Awards for the previous few years. Flanked by film journalist Danny Leigh, Winkleman’s tenure lasted until 2016, after which hosting duties went back to the Film ’72 standard, with a rotating line-up of hosts.

A variety of faces would go on to front the programme during that final flourish (such as Zoe Ball, Edith Bowman, Charlie Brooker and Clara Amfo), but by now the annual helping of episodes had been reduced from the doughy dollops of years past, to mere fun-sized episode orders in the early parts of 2017 and 2018. The final episode saw Al Murray hosting alongside critic Ellen E Jones and writer Deborah Frances-White, as Ready Player One, Isle of Dogs, Journeyman were the final films served up for their consideration.

Phew, another update in the bag. I can’t help but wonder which centennial milestone everyone will be marking by the time we reach the top spot on the list. My guess: the hundredth anniversary of me starting this list. Anyway. See you next time, pop pickers!

6 responses to “BBC100: The 100 Most-Broadcast BBC Programmes Of All Time (50-46)”

Great read again, Mark. Utterly useless info, but ‘B.Bira’ who raced in the 8th October 1938 motor race, was the Prince of Siam, his full name being Prince Birabongse Bhanudej Bhanubandh (no wonder RT used his pseudonym). He raced all the way up to Grand Prix and Le Mans level and after retiring in the mid-fifties, took up competitive sailing, competing in four summer Olympics up to Munich ’72.

LikeLike

That’s not useless info, that’s *excellent* info. If it’s okay, I’ll add that bit of gold to the entry.

LikeLike

IT’S CANADIAN YOU BASTARD

LikeLike

CO-PRODUCTION BETWEEN WGBH BOSTON AND MONTREAL-BASED CINAR, I THINK YOU’LL [checks location of Montreal] YES NEVER MIND I’VE UPDATED IT NOW.

LikeLike

Of course Mark, no problem 🙂

LikeLike

[…] Racing(Shown 1741 times, […]

LikeLike